George Russell was an old man when he started working for my grandfather.

You probably won’t know who George Russell is but, if you are a gardener, you likely recognise the name from the Russell lupin – a beautiful, multi-coloured, easy-growing perennial that has added a kaleidoscope of colour to gardens around the world.

Back in the 1930’s, Mr Russell was in his 70s and had been developing lupins for well over a decade. He did this mainly in allotment gardens around York, since his own home was gardenless. He still worked as a jobbing gardener because, despite his age, he had a sickly son and a serious lupin addiction to feed.

This is how our family met him. My grandfather was a director of Rowntree’s, the York chocolate makers. Having started there as an engineer, he made a name for himself designing the plant that made Smarties (the British equivalent of M&M’s).

His elevation to management meant he could rent a sizeable Arts & Crafts house that boasted a tennis court and a greenhouse. He gave Russell the run of the latter, and Russell used it as one more site to grow new varieties of his lupins.

As the Gilderdale family gardener, Russell got to know my father rather better than he probably wanted – a dogged eight or nine-year-old shadow with a burgeoning horticultural obsession and deeply in love with the colourful flowers in the greenhouse. In fact, Dad’s artistic talent was discovered when he started designing seed packets with flowers on them.

Imagine, then, my father’s surprise and distress when, one day in 1935, men turned up with a van and carried off all the lupins.

Russell, aged 78, after years of refusing to so much as gift a lupin plant or seed to anyone, had finally been made an offer he couldn’t refuse. Baker’s Nursery had offered him a house, creative control, and naming rights over the ‘Russell Lupin’. His employment with my grandfather and other clients ended and he relocated to Wolverhampton where Bakers scaled up production.

After a couple of years, they were ready to release the plants and exhibited them at Britain’s premiere floral event, the Chelsea Flower Show.

Russell lupins were a sensation. The nursery was awarded a gold medal and Russell received the Royal Horticultural Society’s highest award, the Veitch Memorial Medal.

Before he died, aged 94, Russell was awarded an MBE and, on his death, the humble York gardener was even afforded an obituary in The Times – an indication of his work’s impact.

In 2013, Russell lupins were chosen by the Royal Horticultural Society as the flower of the 1930s and placed second among the decade winners in their ‘flower of the century’ competition (edged out of top spot by the Geranium Rozanne).

Given all the love that people have shown Russell lupins, it is not surprising that our family’s small involvement with Russell has been a source of some pride. Hence, I was taken aback when my daughter came home one day loudly cursing lupins.

I should explain that at the time she was working in conservation and tasked with eradicating ‘pest plants’ – those non-native plants that thrive too well in New Zealand conditions. A day of trying to get on top of an area of lupin had got to her.

One could say that, in New Zealand, lupins have become lupine and, in tandem with gorse and broom, are gobbling up the countryside. Consequently, conservationists here have a visceral dislike of all three of them and want them eradicated if at all possible.

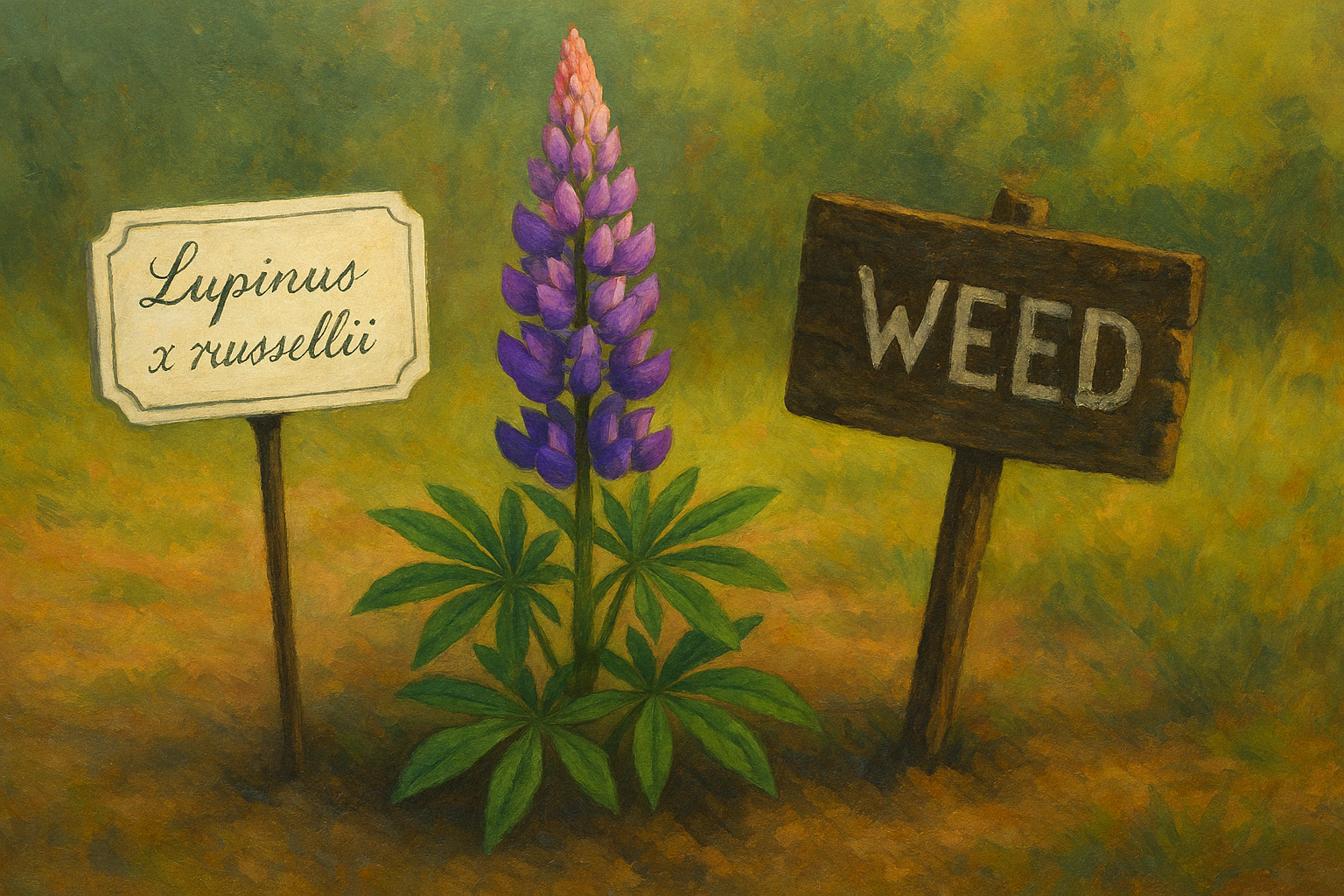

The Russell Lupin, then, is a good example of how one person’s flower is another person’s weed. A thing that is just right in one setting may be quite wrong in another.

The Russell Lupin is a good example of how one person’s flower is another person’s weed.

A thing that is just right in one setting may be quite wrong in another.

Thinking back, I realised that I had encountered this principle much earlier in my life, when an American boy arrived at my Secondary School. He was tall, Hollywood good-looking and loud. And he asked questions. Lots and lots of questions. And made comments in class. Interjected, cracked jokes. The rest of us were in awe.

In 1970s New Zealand schools, if you wanted to talk, you put your hand up. Apart from a small number of younger staff, our teachers just talked and asked us questions. Mostly, the only time we got to ask questions ourselves was when the teacher invited us to ask them. Not surprisingly, this boy disappeared after a few weeks. He had been asked to leave for being too disruptive.

I met him again, just once, at university. By that time, I had figured out the problem. “I bet you never knew why they chucked you out,” I said. “I had no idea,” he replied. “I was just behaving like we did at school back in the States.” And he was.

But normal, enquiring minds, nurtured by a US liberal education system, simply had no place in the hierarchical New Zealand school of the time. The system here still retained vestiges of the colonial model, one that sought to discipline rather than expand or liberate the minds of its subjects.

Like a Russell lupin, an enquiring, questioning mind is a beautiful thing, but it can get you into trouble if inserted in the wrong place – a place where that beauty is seen as inconvenient or invasive.

Happily, though, contexts can sometimes be more fluid than we realise. It turns out that Russell lupins are the equivalent of highly nutritious haute cuisine for sheep, who love eating them.

With nearly five times as many sheep as people in New Zealand, keeping the sheep happy is of no small import, so it may be that lupins get a reprieve. My dad, who adored them, would have been happy about that.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion