How the magic circle of curiosity and care enchants the quality of our attention

Curiosity is a gift we start with but often lose.

We begin our lives with a vibrant and vivid inclination to explore and engage with the world around us, but as part of the fabric of our daily lives, such natural curiosity is a thread that often becomes frayed and faded.

This loss, often a result of being ground down or burnt out by an uncaring world, poses a profound question: What does it mean to insist on relating to the world with curiosity?

Curiosity is more than a mere inclination; it's a form of intellectual care. It's an active, deliberate choice to pay attention, inquire, and seek understanding. It’s about nurturing a caring engagement with the world, exploring and questioning our surroundings with keen interest.

In this sense, curiosity and care are intertwined, both stemming from the Latin 'cura', meaning to care, help, or treat.

To insist on relating to the world with curiosity and care is to live consciously inside a 'magic circle' that enchants the quality of our attention.

To insist on relating to the world with curiosity and care is to live consciously inside a 'magic circle' that enchants the quality of our attention.

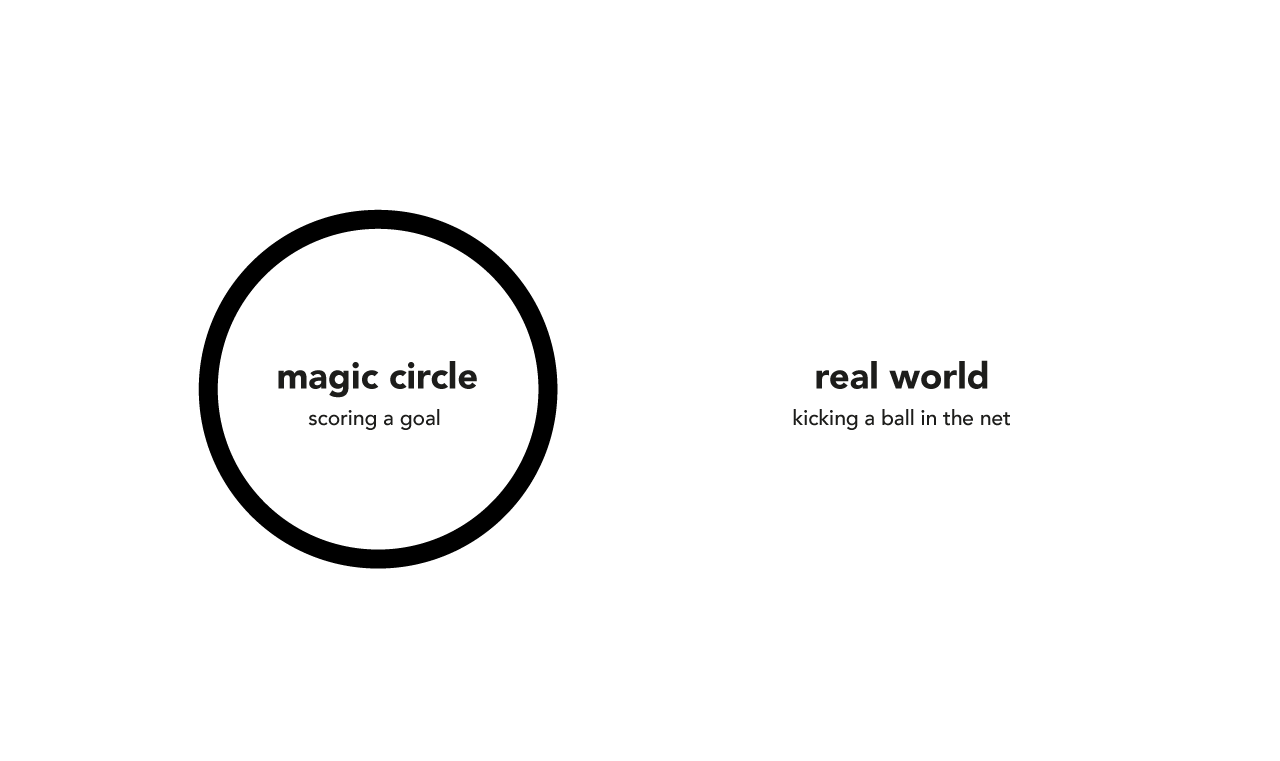

The magic circle concept, credited to Dutch anthropologist of play Johan Huizinga, offers a powerful lens through which we can reframe our interaction with the world. It refers to the space and time in which play happens, creating a separate reality with its own rules and boundaries. Within this magic circle, we willingly suspend disbelief and fully engage with the play world, experiencing a sense of freedom, creativity, and exploration.

Huizinga is emphatic about the status of play in human affairs:

Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing.[1]

For Huizinga, the magic circle is a metaphorical space where the normal rules and realities of the world are suspended, replaced by the playful, the imaginative, and the possible.

The magic circle alters the meaning of our actions and enchants them with power and purpose.

If I am walking my dog on the neighbourhood football field and happen to kick a football into the net, I have merely kicked a ball into a net. But if I kick the same ball into the net inside the magic circle of a football match, then instead of doing something mundane, I have done something else entirely. Something magical. I have scored a goal.

The magic circle is the difference between scoring a goal and merely kicking a ball into a net.

In some sense, we are always in play space, whether we realise it or not. It is part of how we present ourselves in everyday life as we pass through various membranes of social interaction.[2][3]

Whether or not you believe life itself is a kind of game, we know that any kind of playing requires a particular mindset in which we willingly take on the rules of the game, however absurd or inconvenient they might be, so that we can step inside the magic circle and play.

In order to step inside that circle and play — or at least in order to play well — one needs to care, rather than just following the 'rules of the game' by rote.

Bernard Suits calls this adopting a lusory attitude – the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.[4] Without it, no play can happen, whether the game we are playing is called backgammon or boardroom.

I am telling you all this because I want to make it clear that when I talk about what it means to go through life as someone who insists on keeping intact their curiosity and care, I am talking about something deeper than just a bland or whimsical affirmation.

Creating a magic circle of curiosity and care is rather a radical act of re-enchantment, a way to imbue every interaction, every thought, and every moment with a sense of wonder and thoughtful consideration.

When we insist on enchanting the quality of our attention with an attitude of curiosity and care, the magic circle we create means the difference between being present and merely occupying space.

Tell someone who cares: the commodification of attention

In a world increasingly geared towards efficiency and transactional relationships, the art of being present – truly present – is becoming a rare characteristic.

Attention itself has become a commodity, another human resource strip-mined by hyperscaled tech platforms that seek to extract our attention not to enrich us, but to profit from us.

Today it’s harder than ever for us to pay attention, at exactly the same moment that it has become easier than ever to buy attention.

Today it’s harder than ever for us to pay attention, at exactly the same moment that it has become easier than ever to buy attention.

But attention as a commodity can only ever be concerned with quantity and efficiency, rather than quality or connection.

Here’s a personal story that highlights to me how we unthinkingly sacrifice human connection for the sake of efficiency.

For a lot of my early working life I was in retail and customer service, and one of the many short-lived jobs I had was at the Optus phone shop in Brisbane, signing people up to mobile phone contracts.

People used to come in with all kinds of weird and wonderful questions and problems, most of which weren't about them buying a phone or a contract.

One of my colleagues made a little box to put behind the counter and in it he put lots of handout cards with different phone numbers on for technical support, insurance manufacturer warranty, and so on. As the customer started to ask him a question, he'd reach into the box and hand them the relevant card, even before they had finished their sentence.

On the front of the box, facing the staff, but facing away from the customer, he'd written in marker pen: TSWC. Tell someone who cares.

It's quite clever to know what the outcome of a conversation is going to be before you've had it, and we're all familiar with those conversations. In focusing on the outcome, my colleague thought he was being efficient, and he was!

On the other hand, if you want to make absolutely sure that you kill any chance for curiosity, care, or human connection, focusing on the outcome in advance instead of listening and being present is one of the very best ways to do it.

The challenges of caring in a consumer culture

In a world where efficiency and cost-effectiveness reign supreme, the kind of care that being present requires stands little chance.

Care is, after all, expensive—not just in monetary terms, but in the currency of time and attention.

As individuals, we navigate hundreds of financial and social interactions each week. When it comes to making purchasing decisions, even if we aspire to be conscious consumers, we often find ourselves choosing the cheaper, less cared-for option over the one made with care, whether out of convenience, necessity, or ignorance.

Even if we appreciate fair-trade products and artisanal goods in principle and go out of our way to purchase them in practice in some cases, we are unlikely to be in a position to be well-informed or well-resourced enough to devote the care necessary to navigate life as a conscious consumer in every aspect of our lives.

Similarly, though we might aspire to care about all of our friends, it’s likely we struggle to give all the time and attention they deserve in practice. In some cases we may instead simply opt for the efficient use of reaction emojis to give an appreciative thumbs up to all those memes they sent.

Do we care enough to read a whole book or track down an original primary text, or do we ask ChatGPT to tell us what it’s about? Do we go to see the whole movie, or just read the reviews on RottenTomatoes?

In so many areas of modern life, especially those mediated by technology, instrumental logic unconsciously prevails, shifting our attention towards quantity and efficiency while sacrificing the depth and quality of our attention.

Do we care about care? The value of care in society

Meanwhile, on the level of whole societies, we recognise the importance of care yet consistently undervalue it. We all appreciate ourselves and our loved ones being cared for, but the professions rooted in care, vital to the well-being of our communities, are often the least rewarded.

The pandemic starkly illuminated the critical role nurses play in our healthcare system. We lauded them as heroes, standing at the forefront of a global health crisis. We know that nurses routinely face not only long hours and increased workloads but also significant risks to their own health.

Yet, while as a society we may be happy to clap for them during a crisis, our adulation often fails to translate into tangible recognition and support. While society depends heavily on nurses for health and well-being, the profession remains one of the least rewarded in terms of compensation, respect, and working conditions.

This situation mirrors a global crisis in the teaching profession. Educators, who enter the profession with a desire to nurture young and inquisitive minds, are increasingly finding themselves at odds with the systems they operate within.

In the United States, a stark ‘teacher pay penalty’ highlights a growing disparity in compensation compared to other professions. This economic challenge is compounded by an environment of attacks on public education and poor working conditions, leading to high stress and burnout at levels often double that of the general workforce. This has prompted many to seek alternative careers, despite the challenges of transitioning to the private sector.

Internationally, similar patterns emerge. In Anglophone countries like the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, there have been record rates of teacher departures. Economic pressures, coupled with cultural and political shifts, have created a landscape where educators often feel undervalued and unsupported.

There’s a familiar saying: “Don't tell me where your priorities are. Show me where you spend your money and I'll tell you what they are.” If we follow this logic, we would be forced to conclude on the numbers that we don’t care about care.

But it’s not just about money. It’s also about values, recognition, and respect.

Care, a fundamental human need and a cornerstone of our social fabric, is often seen as a given, an expectation, rather than a skilled and valuable contribution. This perception is deeply rooted in cultural and historical contexts, where caregiving has been traditionally associated with unpaid or underpaid labour, usually performed by women.

Even so, the situation with our societal relationship to care runs deeper than just blindness and neglect, as serious and severe as those are. Our social arrangements also routinely step over into active transgression against care.

The concept of moral injury, originally identified in combat trauma, profoundly affects those in caregiving and educational roles, and speaks to a deeper, systemic misalignment.

Moral injury occurs when individuals are forced to participate in a system in conditions that betray their core values and beliefs, leading to deep psychological distress.

It is not just that some people or some systems fail to care. It’s that some people and some systems consistently make it difficult or impossible for those people who do care to act on it, eventually driving them either out of the system, or simply out of their minds.

How instrumental logic erodes human connection

For example, although my heart belongs to the practice of education, my heart has been broken many times by the profession of education and its institutions.

Indeed, my relationship to institutional education has been one of profound and ongoing moral injury. As a student, this led me to drop out of both high school and university more than once. Despite vowing not to let school interfere with my education, I nevertheless eventually accumulated a few degrees and a professional career in higher education. But the relentless moral injury of academia has meant I have since walked away from that world altogether.

My experiences have driven me to spend much energy and effort on grokking the reasons for all this, wondering just what it is about the social and institutional arrangements of our times that makes it feel so impossible to care about the right things in the right way for the right reasons.

If I were to put my finger on one single thing to simplify the complexity of what I’ve found without trying to reduce it, it would be the logic of rampant instrumentalism – where we are always doing something for the sake of something else, and never doing the thing we’re supposed to be doing for its own sake.

As students, we go to school to pass tests to earn grades to win credentials to get jobs. As academics, we apply for grants to win funding to do research to publish papers to boost our reputation to get promoted.

Amidst the business (and busy-ness) of education, there is often little room for the actual practice of education. There is certainly little time for curiosity.

Many other social practices are similarly crowded out by the activities of their associated professions, busy as they are with trying to do efficiently things that perhaps need not be done at all. Hobbies have been crowded out by side hustles, and social media has helped turn socialising into a source of social clout and status.

We give the quality of our attention to anything but the thing itself. Who and what is all this efficiency for?

When instrumental logic runs amok, we get what Richard Livingstone once described as:

‘a civilization of means without ends; rich in means beyond any other epoch, and almost beyond human needs; squandering and misusing them because it has no overruling ideal’.[5]

We even seem unable to avoid bringing instrumental logic into our most intimate relationships, where it’s easy to become so preoccupied with the business of making a life together that we forget to actually live it.

That is to say, we often struggle to enchant the quality of attention we give to our partners with curiosity and care, to be present rather than to simply occupy the same space.

We often struggle to enchant the quality of attention we give to our partners with curiosity and care, to be present rather than to simply occupy the same space.

Tragically but tellingly, when relationships fail, it is often not from a lack of love but from a lack of connection.

Psychologists have noted that relationships can end due to a gradual decline in connection, intimacy, and affection, with common reasons including loss of physical intimacy, trust, and emotional support. This decay of connection, often underlined by feelings of loneliness and self-doubt, signifies a deeper need for curiosity and care in our most personal bonds. Love without active curiosity, without quality attention, gradually erodes the bond, leaving behind a hollow shell of what once was.

Without care and curiosity, our connections fray, until we lose what brought us together in the first place. Sadly, we may be too preoccupied to notice.

Such disconnection and decline is a painful and confusing trajectory for two people to experience. What would it feel like if our entire societies were going through something similar?

Even transactional relationships can be enchanted with care and curiosity

Let me share another story from my days of working in retail, one with a different emphasis.

When I worked at the Apple retail store in Melbourne in the early 2010s, we were encouraged to connect with the people who came into our store, to take time in our interactions to deepen and restore relationships in the name of enriching lives.

Sure, it might be the 250th time you had heard a sob story of how the customer’s expensive smartphone had been dropped and broken. Sure, you had already sized up within seconds of looking at it what the options were and what solution you were going to arrive at. But for the person whose phone and whose story it was, it was a unique experience which deserved the space to be listened to and acknowledged.

We were encouraged to care in acknowledging their situation, align ourselves with them in responding to it, and assure them we would find a solution together, often surprising and delighting them with a free repair or replacement even if it had been their fault.

This quality of attention was considered so important that everyone working in the Apple Store carried around a credo card tucked into their personal lanyard as a constant reminder.

To be clear, I’m not here to shill for the company. Apple is a different beast now, in many ways a capitalist triumph of efficiency and logistics at incredible scale, but not the same place it was during my time there – things were changing even by the time I left in 2012 shortly after Steve Jobs passed away. But it was a memorable experience that left a lasting impression on me.

It taught me that even in busy or routine situations, true curiosity and care involves embracing each interaction as unique, understanding that even a familiar story is new to the person sharing it. It gave me an appreciation for the power of inclusive hospitality.

Hospitality, at its core, is about making people feel cared for. In Aotearoa-New Zealand where I live, the Māori word usually translated as hospitality – manaakitanga – refers to and embodies the practice of showing people respect by giving care, kindness, generosity and support.

Not coincidentally, when Steve Jobs and Ron Johnson — Apple’s then-Head of Retail — sat down to plan what they wanted to be a world-class Apple Store store experience, they famously turned to the world of hospitality for inspiration, enrolling their first retail managers in Ritz-Carlton’s leadership program.

I was most intrigued by the implications of an organisational culture that consciously insisted on hospitality. This came alive most for me when putting into practice another Apple Store principle – to always assume positive intent.

Assume positive intent is the idea that everyone has something going on and you don’t know what’s going on for them outside of what you’re seeing in the interaction, so you assume they have good intentions even if right now they are being a pain in the ass. When you assume positive intent, the interaction goes better for everyone, and sometimes magical things can happen.

Even if you know someone doesn’t have positive intent, acting as if they do can sometimes be a reframe that turns out to be disarmingly effective. It can restore their positive intent.

And what if someone is brazenly lying to your face or even stealing from you? We were told to simply let them take the stolen goods and walk out.

I thought about this a lot, and I saw it happen more than once.

For the people thinking about an Apple Store culture that insists on hospitality, the power of assuming positive intent was so important as a principle, that you insisted on it even at your own expense and in situations where you know you’re being taken advantage of, because what matters is ultimately not who they are, but who you are.

Although the Apple Store and the Optus shop were both basically the same kind of job, this was a long way from the Tell Someone Who Cares box. I never saw anyone overwhelmed with tears of joyful surprise at the magic of human connection in the Optus shop.

Hospitality and the practice of crafting caring experiences

Someone else who insists on hospitality is restauranteur Will Guidara, whose book Unreasonable Hospitality tells the story of how he and his chef colleague Daniel Humm went about turning middling New York brasserie Eleven Madison Park into a fine-dining establishment that eventually topped the list of best restaurants in the world.

The signature story of the book involves a hot dog, a powerful example of what it looks like to turn ordinary transactions into extraordinary experiences.

In early 2010, during a busy lunch service, Guidara overheard a table of four foodies discussing their trip to New York City. They had been to some of the best restaurants in the city but mentioned that they hadn't tried a New York City hotdog. Inspired by their conversation, Guidara quickly ran into the street to a nearby hotdog cart, bought a hotdog, and returned to the restaurant. The chef cut the hotdog into four perfect pieces and plated it with a fine-dining flourish. When the hotdog was brought out to the table, the customers were thrilled. In fact, it became the most memorable highlight of their entire trip.

Guidara says this experience taught him the importance of making people feel seen, welcome, and experiencing a sense of belonging in a restaurant. As he puts it, the food, service, and design are just ingredients in the recipe of human connection, which is the essence of hospitality.

What’s striking to me about the hotdog story is that it wasn’t efficient, or routine.

It wasn’t done for the sake of something else. It only made sense at that particular moment in that particular way, and was only possible at all because Guidara had been listening and paying attention to the guests in the first place.

The hotdog was a one-off. You can’t replicate it, and if you did it would lose its enchantment immediately.

But you can make such spontaneous acts of hospitality characteristic of your way of being. Guidara goes into dizzying detail about how they go about consistently creating these one-off moments, which he calls ‘legends’.

In case this all sounds familiar, Guidara’s hotdog story also inspired the standout ‘Forks’ episode of the TV series The Bear, a show all about human connection in the world of hospitality.

Incidentally, I was so intrigued by all this that when we had our first in-person Grokkist meetup in New York last year, I took my team of two to Eleven Madison Park both to appreciate and analyse an experience of unreasonable hospitality.

More broadly, this ethos of creative spontaneity as a repeatable process echoes that of Creativity Inc, former Pixar president Ed Catmull’s story about what it takes to insist on maintaining a culture of curiosity and care at a genre-defining commercial animation studio, and why it’s so difficult even when it’s your number one priority.

Insisting on curiosity and care opens a pathway to human flourishing for all

If it isn’t clear by now, what’s at stake in all this is the potential for connection and human flourishing. The practice of curiosity and care, expressed through a simple act of hospitality, can transform a mundane transaction into an enchanting experience.

Surely this is an ethos we can afford to bring to all kinds of people and experiences, not just those who are in a position to buy a new iPhone or indulge in fine-dining experiences.

Interestingly, Will Guidara’s Unreasonable Hospitality book is subtitled ‘the remarkable power of giving people more than they expect.’ I think it’s worth emphasising that the darker unspoken implication of giving people more than they expect in this sense is that people don’t really expect to receive curious or caring attention, even in the context of an expensive fine-dining experience.

Instead, we might expect transactional relationships and efficient service in most of our social interactions, but we don’t expect genuine hospitality. We have learned not to expect curiosity or care.

And people largely don’t expect these things from us either. In fact, in many day-to-day situations, we are supposed to sacrifice them at the first sign of inconvenience.

But what would change in our societies if we insisted on curiosity and care?

If we enchanted our everyday interactions with curiosity and care, could we create a more democratic and compassionate society? Could we redefine the way we value and recognise the contributions of caregivers, educators, and those who embody the spirit of hospitality? Could it be that through these intentional acts of kindness, empathy, and connection that we re-enchant our communities, uplift one another, and foster a culture that celebrates and prioritises the well-being of all?

As with many problems that we think ‘they’ should do something about, it turns out that the ‘they’, ultimately, are us.

Or, to put it another way, curiosity begins at home.

What does it look like to be someone who insists on curiosity and care? How do we recognise such a person, and how can such people recognise each other?

Outlaws of ethos: the challenge for curious souls

If you are the kind of person who has made it well into adulthood with your curiosity still intact, please accept my sincerest congratulations – this is in itself a significant and likely costly achievement.

And if you are somewhere on the journey to rediscovering, reawakening and reclaiming your curiosity, congratulations also – this is sometimes an even harder and more uncertain path.

One of the under-appreciated principles that makes a democracy work is that while no group is allowed to get everything it wants, equally, no group is allowed to be left out altogether.[6]

When people can’t recognise themselves in the culture, language and systems they are part of, they no longer feel they that have a stake in those things. When we experience such alienation over a long period of time, it is rarely a good thing, either for the system or for ourselves.

For people who insist on bringing curiosity and care to a world that values instrumental logic over intrinsic goods and effectiveness over excellence, it can be often hard to recognise ourselves in the culture and language of our societies. It can be hard to feel we have any real stake in what exists.

We might feel like we are trying to eke out an existence between the cracks of a world that was never made with us in mind.

We might feel like we are trying to eke out an existence between the cracks of a world that was never made with us in mind.

We might see ourselves as canny outlaws, quietly wielding uncaring systems against themselves from the inside, bending the rules where possible, and putting a thumb on the scales of existence to make a small difference wherever we can.

We might feel we belong in another age entirely, either one long since past or perhaps a future one of our fond and frequent imagining.

Or we might just be aiming to find a way to live a meaningful and dignified existence while simply passing through, taking nothing but memories and leaving nothing but footprints.

While our individual stories and situations are undoubtedly unique and unrepeatable, there are discernible patterns and flavours to our shared psychological and spiritual experience.

I know this, because every time I encounter one of these people, they stand out. Meeting one of them feels like suddenly discovering what colour is after only ever living in black and white.

Then I started meeting more of them, and I realised that everything was in colour all along, it’s just that most of us are taught or learn to choose grey.

As I started encountering more insistently curious and caring people and collating our wildly different yet eerily similar adventures, it began to dawn on me that we needed a shared vocabulary and social language categories to describe our experiences.

Beyond the generalist: the many faces of curiosity

As it turns out, there are already a lot of language categories available for the kind of person who allows themselves to be led through life by their curiosity. This is because it usually leads such people to wander around accumulating many different kinds of knowledge and experience from all over the place and combine it into a unique synthesis that only they could ever arrive at.

As a result, the world tends to call such people ‘interdisciplinary experts’ if we are being kind, ‘generalists’ if we are being polite but sceptical, or a 'jack of all trades' when we want to emphasise the sceptical part.

Having your curiosity still intact often leads to being a generalist because it fuels a thirst for knowledge and a desire to explore different areas of interest.

When curiosity is alive and well, it pushes us to ask questions, seek new experiences, and engage with a wide range of subjects. This natural inclination to explore and learn beyond the boundaries of a single discipline or specialisation is what often leads to a more holistic understanding of the world.

Curiosity drives us to connect the dots between different fields, uncover patterns, and gain insights that can be applied across various domains. As a result, people with a curious mindset are more likely to embrace a generalist approach even if they happen to inhabit a specialist field of practice, as they find joy and fulfilment in the continuous pursuit of learning and the exploration of diverse disciplines.

Beyond ‘generalist’, terms like 'multipotentialite' or ‘multi-hyphenate’, while clumsy to pronounce, do capture the essence of those who find potential and passion in various fields.

Similarly, 'polymath' or 'Renaissance person' suggests a more positive view, celebrating the ability to excel across diverse disciplines, and situating wide-ranging interests as strengths rather than shortcomings.

There are also metaphors drawn from the animal world, for example the fox who knows many things as opposed to the hedgehog who knows one big thing, or the hummingbird who flits delightfully from one flower to another, busily and beautifully being a cross-pollinator.

However, it's not just the range of knowledge that's important to capture, but the depth and quality of engagement. Here, the term 'deep generalist' might be more fitting, indicating someone who not only spans a wide range of fields but also seeks profound understanding within them. This is akin to the concept of 'T-shaped skills', where one has broad knowledge (the horizontal bar of the 'T') complemented by deep expertise in one area (the vertical bar).

There’s also the language of ‘neurodivergence’, which acknowledges a natural variation in neurological functioning and cognitive processes among various people that leads to different ways of perceiving, processing, and experiencing the world. Neurodivergent traits can include a basket of conditions such as autism, ADHD, synaesthesia, dyslexia, and more.

Although the language of neurodivergence has strong connotations with a medical model of human understanding – it’s something you can be diagnosed with – many people who insist on curiosity and care have found it affirming precisely because it offers categories of identity that help them recognise and communicate their own experience in a way others can understand and relate to. This includes proliferation of intriguing subcategories like AuDHD (autism with ADHD) that are becoming identity markers in their own right.

Aside from the potential for social stigma that comes with adopting the language of neurodivergence, another commonly remarked-upon limitation is that such language tends to describe how the symptoms of this way of being in the world are perceived by others – often in terms of their inconvenience – rather than what it feels like to live it from the inside. It can feel like language that is about us without necessarily being for us.

The grokkist: a champion of curiosity and care

All these language categories capture different facets of a complex and multidimensional identity. They each tell a part of the story of individuals who navigate the world with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and a profound commitment to understanding.

All of which brings us finally to the ‘grokkist’, which is the name I give to people who insist on relating to the world with curiosity and care, including myself.

For me, this term transcends the mere accumulation of knowledge or the versatility of skills. It embodies a deeper, more intrinsic motivation - the 'why' behind the learning and doing.

The term 'grokkist' transcends the mere accumulation of knowledge or the versatility of skills. It embodies a deeper, more intrinsic motivation - the 'why' behind the learning and doing.

At the intersection of the various identities we’ve discussed, it is the grokkist who brings these elements together in a harmonious blend, championing a way of being that values depth, empathy, and connection in every pursuit.

The term grokkist is derived from the word ‘grok’, a term coined by Robert A. Heinlein in his science fiction novel "Stranger in a Strange Land." One doesn't need to be familiar with the book or even a fan to appreciate it, however – grokking has since entered the English language more widely and has come to represent a profound understanding that goes beyond mere comprehension.

The word ‘grok’ itself originates from the fictional Martian language created by Heinlein. It carries a wide range of meanings and shades of significance.

At its core, grok means to fully and deeply understand something, to drink it in on a fundamental level. It implies a complete merging of one's consciousness with the subject of understanding, encompassing both intellectual and emotional comprehension.

To grok is to engage with something or someone so intimately that you become a part of it. It is a state of empathy, where you understand and connect with the essence of the other. Grokking involves not only perceiving and comprehending but also feeling and experiencing.

On a personal level, as someone who has an intellectual way of being in the world, I particularly appreciate the ego-less and emotional register of ‘grokking’. It offers a refreshing and appealing alternative set of intellectual connotations to those I associate with the status-driven and emotionally constipated world of academia.

A grokkist, therefore, is someone who embodies the spirit of grokking – someone who groks as a way of being.

Grokkists are people who strive to deeply understand and connect with the world around us. We are driven by an insatiable and intrinsic curiosity and a genuine care for others. Grokkists embrace a multidimensional perspective, going beyond surface-level knowledge to engage with the essence of things, exploring the depth and intricacies of various subjects.

Grokkists are not satisfied with superficial interactions or transactional relationships. We value genuine connections and seek to establish meaningful bonds with others. We listen attentively, ask thoughtful questions, and strive to empathise deeply.

Embracing the grokkist philosophy

Grokkists broadcast a magic circle around them wherever they go, where curiosity and care can flourish, and silently modelling a culture of understanding, empathy, and personal growth.

In an instrumental and commodified world often too busy to care, the existence of grokkists implicitly challenges the status quo. Choosing to be a grokkist is an invitation to an act of quiet rebellion, a declaration that we insist on engaging with the world in a way that values depth, connection, and the beauty of the human experience.

It's a commitment to enchanting the quality of our attention in all our interactions with genuine curiosity and care, to being present rather than simply occupying space.

Going through life as a grokkist is its own reward, and ensures that no matter what is at stake, we have already won. At the same time, grokkists will inevitably feel hurt, lonely and confused at times as we navigate a world that values the fruits of curiosity and care but often overlooks their roots.

Most importantly, by insisting on curiosity and care, grokkists also inspire others to do the same, creating a ripple effect of empathy and understanding.

As we relax into our gifts and step into our power, we can move from canny outlaws to system changers in our respective communities and fields of practice.

At all levels of encounter, a grokkist can’t help but be someone who happens to others, leaving things better than we found them.

Who and what will you happen to next?

- Join our mailing list

- Come to one of our upcoming events

- Be part of our community

- Take one of our courses

- Become a member and support our work

Offline References

[1] Huizinga, Johan, Homo Ludens: a study of the play-element in culture (Routledge, 1944), 1.

[2] Goffman, Erving, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Doubleday, 1956).

[3] Jaakko Stenros, "In Defence of a Magic Circle: The Social, Mental and Cultural Boundaries of Play", Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association 1, no. 2 (2014): http://todigra.org/index.php/todigra/article/view/10/26

[4] Suits, Bernard, The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia (Broadview Press, 2005), 54–55.

[5] Quoted in Barnes, Louis B, Carl Roland Christensen, and Abby J Hansen. Teaching and the Case Method (1994), 58.

[6] Freudenberg, Graham, A Certain Grandeur: Gough Whitlam's Life in Politics (London: Penguin, 2009), 29.