I doubt that anyone who lived through the 1970s (in the Anglo/American world, at least) will fail to recognise the words ‘Go Placidly’.

They begin the Desiderata, a poem that, in one form or another, graced the walls of any hippie-adjacent household of the period. We all knew that this quiet, calming poem came from Old St Pauls Church, Baltimore, dated 1692. The prints always said it did. Except it didn’t.

I can’t remember exactly when I discovered that the Desiderata was the work of a twentieth century poet, but I most certainly remember my indignation. It felt like some sort of cynical marketing ploy, and I have subsequently been unable to read the text in the same way. But it turns out that the Desiderata’s story is less straightforward than I initially assumed.

Max Ehrmann, a not particularly fêted poet, wrote the piece sometime before 1927, when he copyrighted it. Its subsequent history was one of sporadic unacknowledged reprints before, in 1956, the rector of St Pauls Episcopal Church published the poem for his parish, in a work of inspirational texts.

But, in the literary equivalent of what was once called ‘Chinese Whispers’ (but you may know as ‘Telephone’), the original byline got mangled. That original had mentioned the poet, the church and the date the church was founded – 1692. But the version that eventually took the world by storm had lost the poet, and focused on the date, saying ‘Found in Old St Paul’s Churchyard, dated 1692.’

One of the side effects of people thinking that wisdom comes with age is a tendency to create the trappings of age, even when there are none. We can draw a parallel with jeans. People pay large amounts to buy ripped, torn and faded garments. The process is called ‘distressing.’

One of the side effects of people thinking that wisdom comes with age is a tendency to create the trappings of age, even when there are none.

One good recent example of distressed linguistics at work is the word ‘coddiwomple,’ – defined as ‘to travel purposefully towards an as-yet-unknown destination.’ This neatly sums up the process behind Flirting with Wisdom (and Grokkist generally).

Nevertheless, the word ‘coddiwomple’ itself is so new (perhaps seven or eight years old), and so tied to the internet that, at the time of writing, it has yet to show up in Google’s Ngram Viewer (which bases its algorithm on digitised books).

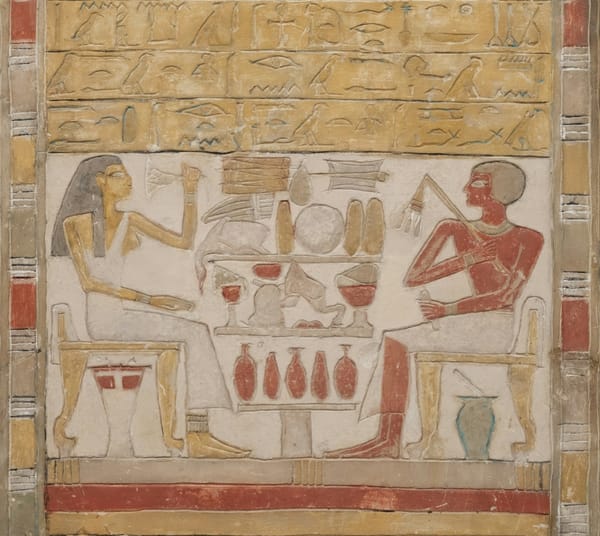

Search for ‘coddiwomple’ online, though, and you’ll find its imagery, and a good few explanations trying to pass it off as old English slang. Perhaps this is because it sounds like the medieval word ‘wimple’, or perhaps it is just that people are genuinely more comfortable if something feels like it has a pedigree. It absolves you of having to decide if that something is good; it has proven itself over time.

It absolves you of having to decide if that something is good; it has proven itself over time.

I have yet to discover who came up with ‘coddiwomple,’ but I’d love to know how they did it. I have several times tried to initiate new words, and they have never taken.

Douglas Adams wrote a whole book that gave definitions to concepts that lacked a name. He linked these to interesting sounding placenames. But none of them has taken off either (at least to any great extent), even the good ones that ought to have, like ‘Epping (participial vb.) The futile movements of forefingers and eyebrows used when failing to attract the attention of waiters and barmen.’

Max Ehrmann was in his fifties when he wrote the Desiderata, and he clearly thought that he had created something important, for he copyrighted it. Yet it was a slow burner. He must have felt like that person trying to attract a waiter’s attention, and he never lived to see the widespread attention his work would later receive.

Looking at it now, after having ignored it for several decades, I can see that I still carry much of it with me. It was never startlingly original, but it summed up some of the best approaches to living that were available at the time.

The Desiderata may not have been written in 1692, but it is now nearly one hundred years old. The fact that it is still around, and that people are still responding to it, is testament to its being able to capture a reasonably timeless moral quality.

Such historic texts can be deeply helpful, but that shouldn’t stop us trying to remake the ideas for ourselves. As I said at the start of this series, we still need to recreate wisdom for it to remain fresh. Hence, there is a place for both wise older texts like the Desiderata and for new wisdom, even when it is encapsulated in a single word, like ‘coddiwomple.’

Such historic texts can be deeply helpful, but that shouldn’t stop us trying to remake the ideas for ourselves.

Perhaps wisdom really is a mix between some basic human touchstones and purposefully following a moral route, despite not having a clue where it is taking you. I’m pretty sure that is what Max Ehrmann must have done prior to writing the Desiderata.

And while it is good to try and synthesize your experience like Ehrmann did, I think that wisdom comes less from having the answers neatly gift-wrapped, and more from nurturing an experiential journey towards destinations unknown. Call it coddiwisdoming if you like. And that really is a new word.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion