Does happiness come when you look for it directly? Not in my experience. Rather it tends to pop up randomly as we meander along.

I note this point merely to cue you, the reader, to the fact that this piece will, necessarily, meander through a fair bit of territory before it lands in the place you might have been expecting, given the title. So, relax and enjoy the journey!

When the New Year heralded the start of the 1980s, I was happily working on a dig in Egypt. It was a fascinating experience.

My Egyptian history lecturer, Naguib Kanawati, had got permission to work on a necropolis outside a town called Sohag. His research led him to believe that this out-of-the-way site, near a village called El Hawawish, had been a major burial place during the Egyptian Old Kingdom, and he turned out to be right.

With a $5000 grant from National Geographic to fund the entire expedition (at a time when a typical season might cost upwards of $70,000), he assembled a team of New Zealand and Australian students for his first excavation at the site.

I was one of those fortunate enough to be chosen. For the privilege, we all paid our own way and lived in a ‘hotel’ with no hot water, got used to being the only Europeans in a town of a million people, and discovered that the only way to get to our site was to bribe multiple military checkpoints every time we wanted to go there.

There were some major culture shocks to negotiate, but we were immeasurably helped by having engaged the services of a taxi driver called Amin, who guided us through the nuances of cultural clash – mostly by yelling loudly at anyone who got in our way.

It was heady stuff.

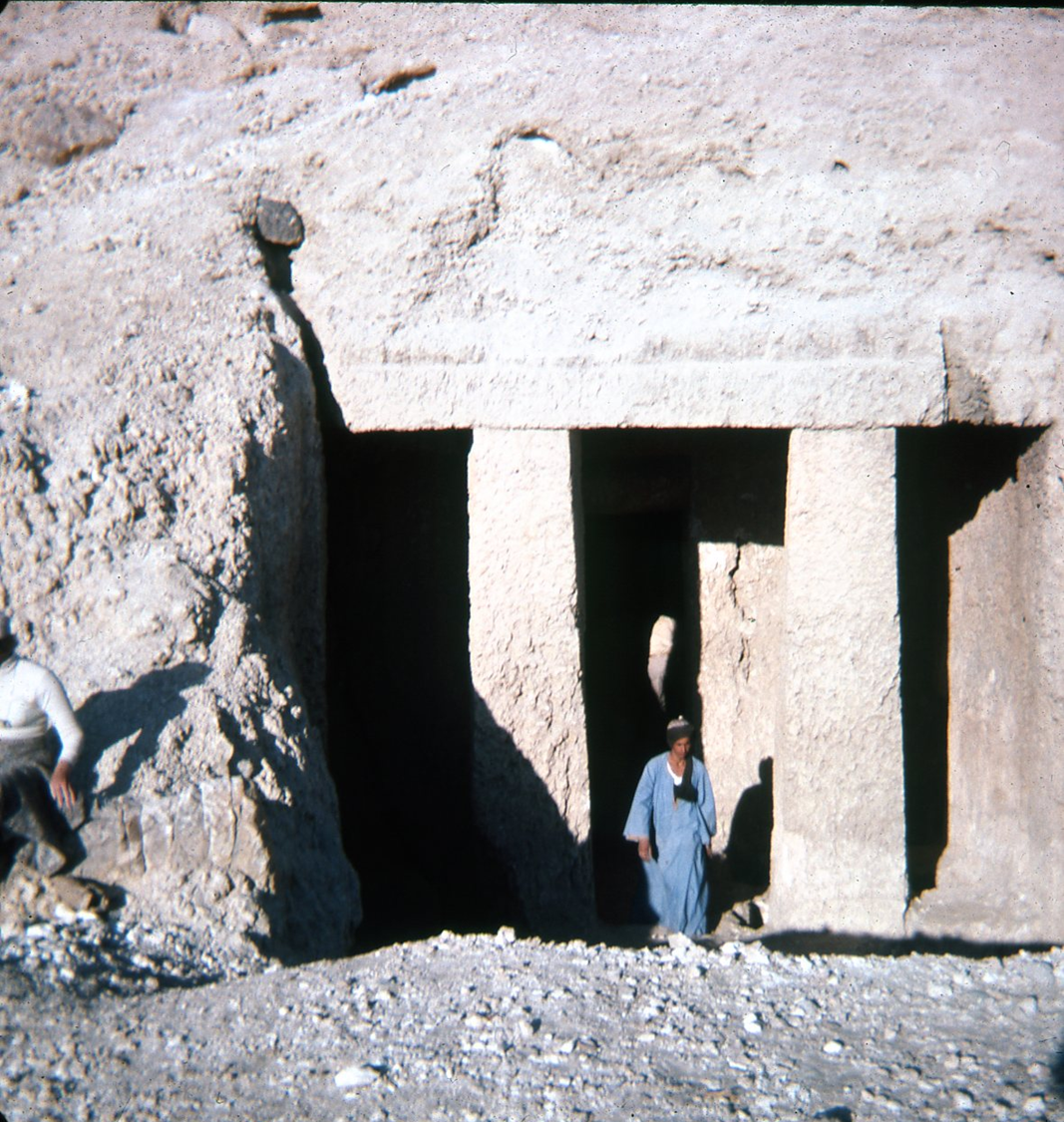

Here are four images of El Hawawish - a view of the mountain to give scale, one of people climbing up the steep slope towards a tomb, one that gives a sense of the site, and one of a major tomb with one of the foremen in front of it.

One of the things that became apparent after a few weeks in Egypt, was that the history of Ancient Egypt had been written largely using what I came to think of as the rule of fives.

The results you read about came from archaeological sites that lay within a five-mile radius of a five-star hotel.

Egypt, at that time, was full of sites like our one that were not located in tourist towns and had yet to be thoroughly explored – simply because they would have required Egyptologists from exalted universities to rough it.

Obviously, tourist towns develop around the most scenic Ancient Egyptian sites, but there was so much more to be found beyond these narrow limits.

Our local Antiquities Department gossip told us about some geologists who had discovered a pristine ancient temple in a remote part of the desert but found that no one in the Antiquities Department was willing to acknowledge the discovery. This was because it would mean having to station departmental staff to guard the site, and none of them wanted to be that person, stuck in the middle of the desert.

As with pampered Egyptologists, personal comfort trumped expanding scientific enquiry.

Our site at El Hawawish would have been a hard-sell to tourists back then.[*] You had to climb a steep semi-mountain to get to the site. The tombs were full of rubble and had been thoroughly pillaged over the millennia.

Though most of the artwork was damaged, there was still plenty for historians to glean. For example, we discovered perhaps one of the oldest signed works of art in existence.

But our ability to do this work relied on someone first moving the encroaching sand and debris away. We thus got to know the local dynamics via the labourers we hired.

The men charged with overseeing the job were senior villagers – wealthier than most, and with good donkeys. They valued Western commodities and, in 1980, the status symbol they most aspired to was a good digital watch.

Although our budget was minuscule in western terms, we had the potential to make a few locals rather wealthier. To this end, and in sympathy with western methods for maximising profit, these foremen hired the cheapest labourers they could find – which turned out to be a group of the local Coptic Christians.

In our little corner of Egypt, at least, the Copts were at the bottom of the social heap. Paid a pittance, they had every reason to come across as downtrodden victims. But they didn’t.

The Coptic workmen were among the happiest people I had encountered — despite being at the bottom of the social heap.

Over the two months I was on site I managed to assimilate enough of the local Arabic to follow bits of conversation.

What I pieced together was that the wealthy foremen were, generally speaking, discontented with their lot, while the Coptic workmen were among the happiest people I had encountered.

It fundamentally challenged the prevailing western notion that money and happiness are somehow linked. Instead, what I could glean of this group of Copts was that they had an incredibly close-knit and supportive community. They may have been poor in monetary terms, but they were socially wealthy.

Happiness, in other words, seemed to reside more in community than material wealth.

This insight was reinforced a few years later when I heard a talk by a social worker from a major European capital.

She had chosen to work with some of the people she regarded as most at risk of depression and isolation – the wives of diplomats. This choice was frequently challenged by others in her profession who thought she should be working with the poor and underprivileged, but her point was that wealth and privilege did not equate to happiness.

The women she worked with suffered through having tiny social circles and being disconnected from their support groupings. It made for great unhappiness, and to my mind she was entirely justified in focusing on this group.

Anyway, when I arrived back in New Zealand after my time in Egypt, I had a new world view, and my revised notion of where happiness resides shaped my subsequent career.

When I arrived back in New Zealand after my time in Egypt, I had a new world view that shaped my subsequent career.

The focus shifted to relationships cultivated not out of self-interest but from respect and a real desire for the other party’s wellbeing. It meant working to create genuine community, which also led to foregoing those transactional relationships that you so often find in work situations, where people try to use one another for some type of career advantage.

Rather, I focused on what I could put into relationships, through listening, sharing and nurturing. Not that I always got this right, but I was certainly happier when focusing on these things than on what I could do to achieve particular career ambitions.

Margaret Thatcher, possibly not the happiest of people, famously said there is no such thing as society. I beg to differ. I saw one, working at its very best, in Egypt.

Footnotes

*El Hawawish was opened to tourists in 2021. The mountain now has steps (over a thousand of them) and a visitor centre. I’m so happy I got to see it in its earlier state.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion