The Edwardian postcard craze was the equivalent of today’s social media. You could write short messages (Twitter/X) or share a photograph or a funny picture (Facebook/Insta).

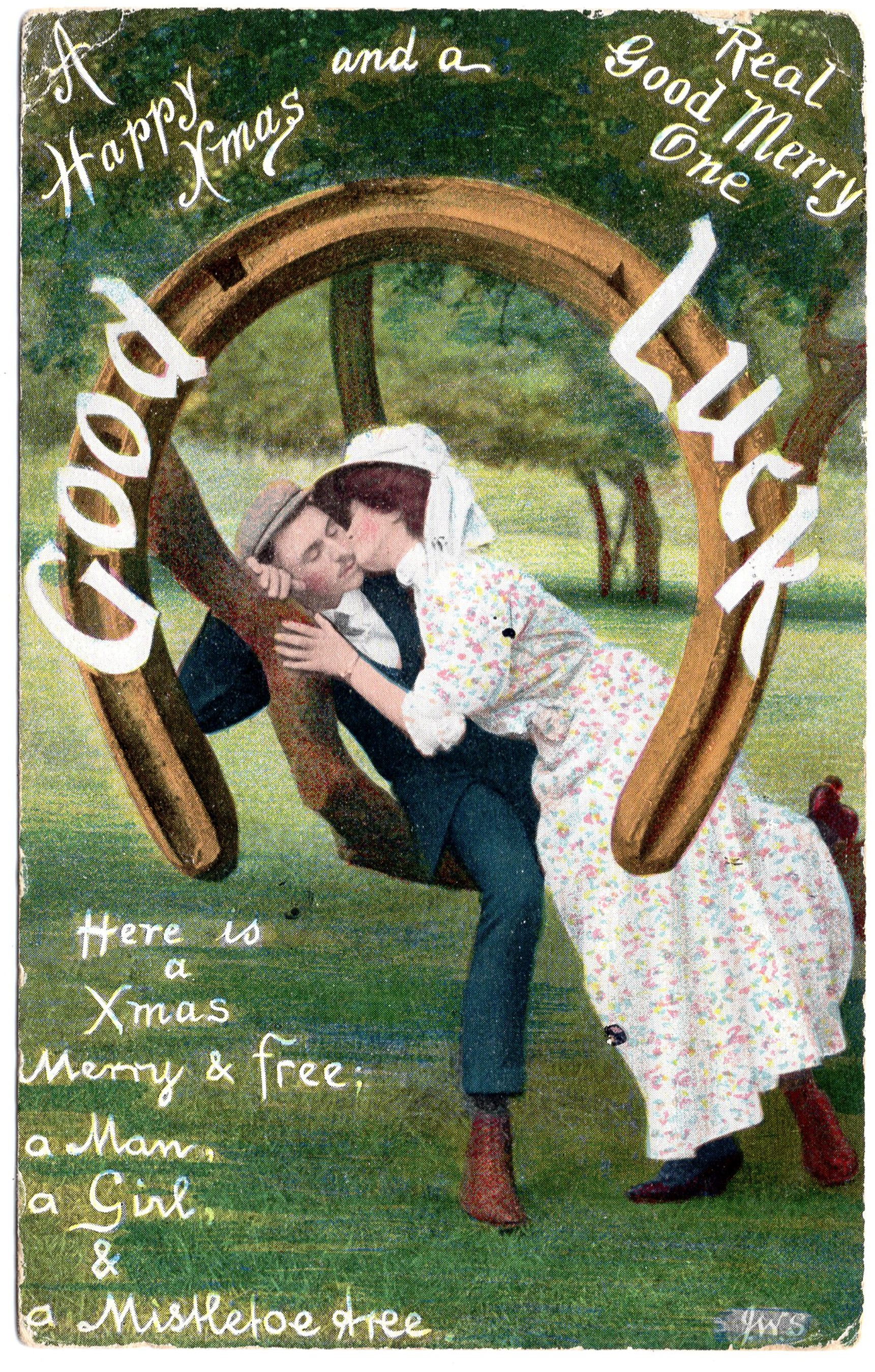

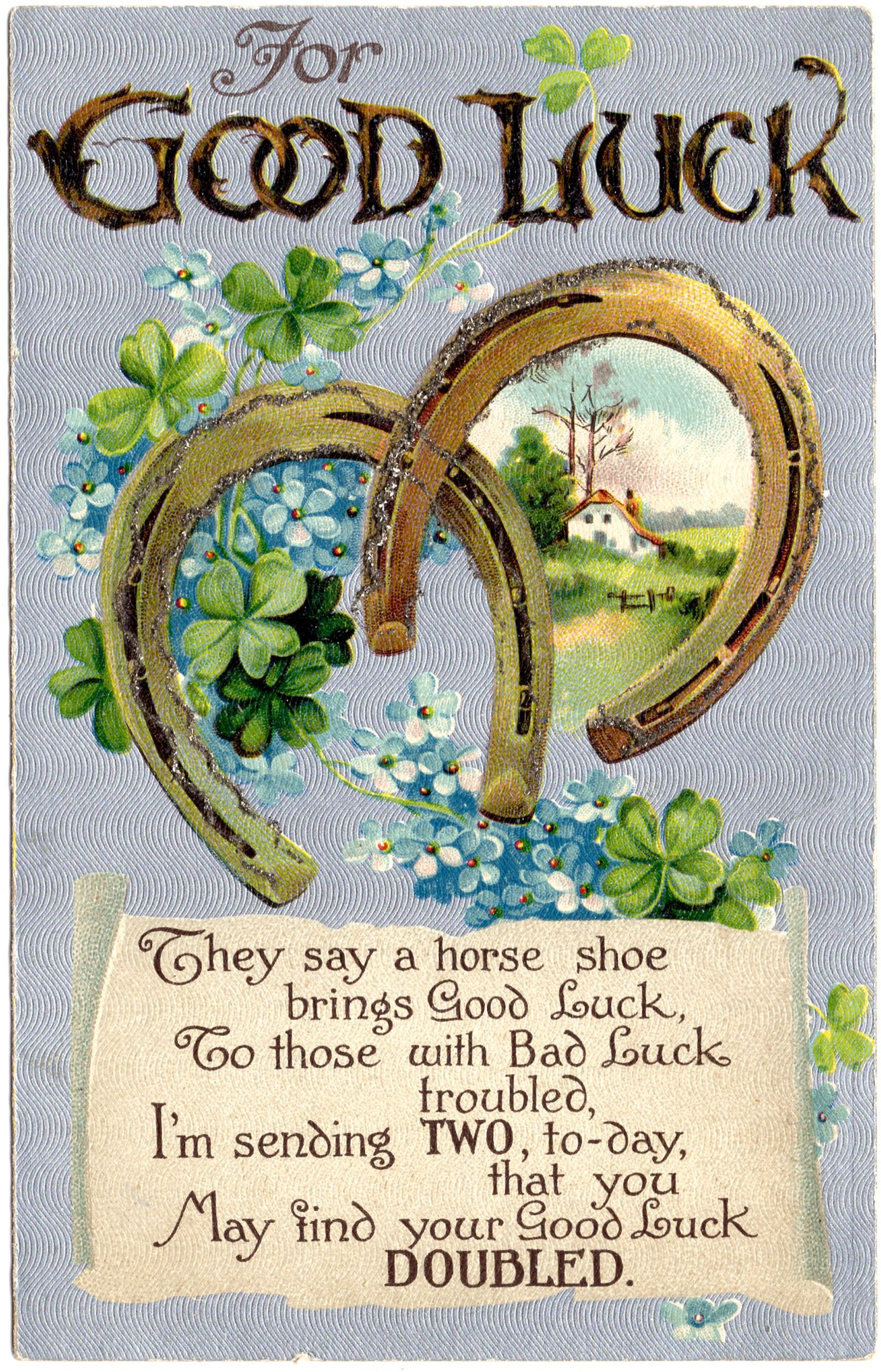

These shared images tell us a lot about the attitudes of the time. While some of the cards were simple views or seaside humour, many others were greetings cards. One of the most common among these was the ‘good luck’ card.

It may seem fairly innocuous to wish someone luck. Hoping that something unexpectedly nice will happen to someone is surely a reasonable wish?

But, as Jackson Lears, in his wonderful book Something for Nothing: Luck in America points out, luck is actually a societal dividing line. It separates the poorer and more dispossessed members, who believe in it, from the more affluent, who adhere to the view that success is a moral reward, earned through the good behaviour of hard work.

From this perspective, undeserved luck (like winning at the lottery or races) is somehow reprehensible.

Edwardian etiquette books (written primarily for the wealthy) are scathing about postcards, saying that no one with social pretensions should insult the recipient with such an offhand form of communication. If you had leisure enough to write a letter, why fob someone off with a postcard?

For newly literate workers, though, postcards were a gateway to the world of letters, and hence the design of postcards caters for a working clientele. It is because of this that Luck figures extensively.

For newly literate workers, postcards were a gateway to the world of letters. It is because of this that Luck figures extensively.

We may have moved on a century from the Edwardians, but the debate around luck versus hard work has barely changed. One can still find successful (usually right-leaning) people who regard success as earned.

A former New Zealand Prime Minister is a perfect example of the success narrative. A smart boy, raised by a single mother in a working-class neighbourhood, he managed to make a fortune as a trader on the stock market.

Now there can be no doubt about the hard work and excellent qualities that brought about this success. But what about the role of luck?

He started out with a luck-deficiency (unlike someone like Winston Churchill who was born into wealth and power) but his early working life coincided with the stock-market boom of the 1980s. This was luck. How many people of equal ability and ambition foundered because they started out around the market crash of 2009?

I would be surprised if there is any successful person who has not at some stage been fortunate in some way – such as having useful contacts or someone who could support them through hard times and set-backs.

Similarly, how many hard-working individuals have been unable to cut through for want of patronage or a safety net? It’s so much easier to take a financial risk when you know someone will bail you out if it doesn’t come off.

It is illuminating, too, to note that the images of horseshoes that festooned Edwardian Good Luck postcards almost always showed the horseshoe facing downwards – so that luck could shower out onto the recipient.

Nowadays we assume that horseshoes should face upwards, so we can hoard our luck rather than share it. Somewhere in the twentieth century a particular type of generosity got lost.

For better or worse, it seems to me that luck is always going to be a part of the equation in achieving success. And acknowledging this should allow us to show more compassion for people who have been dealt the proverbial poor hand.

I recently saw a report on a charity drive asking people to donate food to the Women’s Refuge. Poorer areas consistently gave more than the affluent ones. People who are short on luck apparently empathise with those who have even less.

People who are short on luck apparently empathise with those who have even less.

People who think they have worked hard for their material success, on the other hand, are somehow less likely to share it. Success, it would seem, is not necessarily an indicator of moral worth.

All in all, the sooner people stop using the hard work = success narrative as a comfortable way of dismissing the poor and unsuccessful as underserving, the better. But good luck trying to make that happen.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion