Sometime around the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a change took place in the way people talked about themselves.

Victorians had generally valued a good character as the touchstone of worth. People of good character behaved charitably and treated others with courtesy and kindness. Bad characters did not. We still talk about people in books, films and television as characters – a left-over from this sort of thinking.

From the Edwardians onwards, however, people started looking instead for personality traits. A personality might be bubbly or morose, outgoing or ego-centric.

This linguistic shift from character to personality may seem relatively minor, but it is not. Character is a moral quality. It is earned. Personality is more likely to be seen as innate – something we simply have.

Fundamentally, this shift is representative of a move away from religion and morality as defining our identities, towards psychology (and later genetics) becoming the touchstone for who we are.

Fast forward to today, and we find people obsessed with identity and authenticity. With far fewer people in western culture identifying with a religious grouping, we tend to look for identity elsewhere.

While areas like class, culture and occupation can all furnish identities, currently it is race, gender, sexuality, brain patterns and physical capacity that are widely looked to by young people trying to figure out who they are.

These identities provide them with a tribe to be part of and to defend. They are also predominantly based on our physical and psychological hard-wiring.

Identities provide young people trying to figure out who they are with a tribe to be part of and to defend.

There is very little in these identity starting-points to guide us on how to deal with other people.

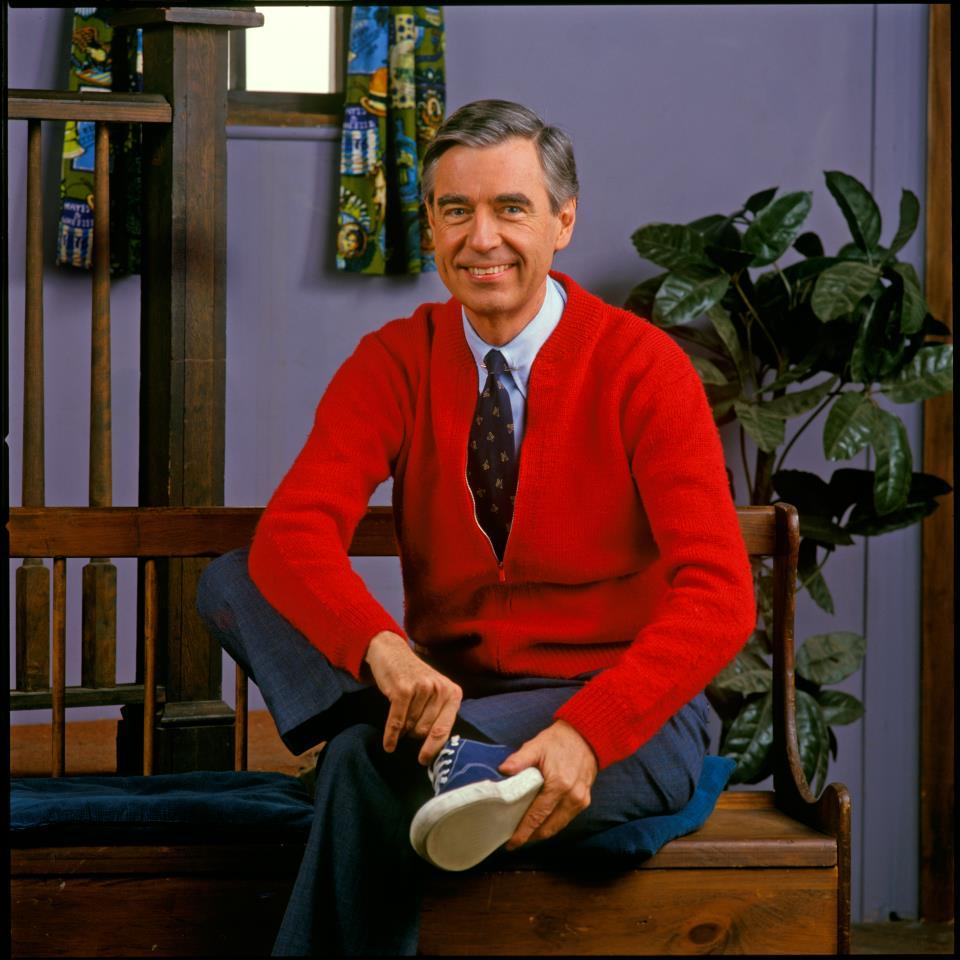

Enter, stage left, the mild-mannered Mr Fred Rogers.

Until very recently I had never heard of Mr Rogers. His long-running children’s television show never aired in New Zealand (as far as I know). Yet he seems to have been one of the most beloved figures in American TV – enough to have justified Tom Hanks playing him in the 2019 film “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood”.

It was this film that introduced me to the way that this unassuming man had been subtly shaping several generations of American children.

Through quietly, but honestly, dealing with the complex and bewildering issues that our kids encounter, his show became a haven for many children whose lives might otherwise have been entirely bleak. Very gently, he encouraged them to behave in humane and kind ways.

He helped, in other words, to shape their characters.

When asked by a television interviewer about the cultural obsession with achieving fame and wealth, Mr Rogers said that there was nothing wrong with fame and wealth, but these should not be the first priority. What he wanted to encourage was for people to be helpful.

Just imagine, for a moment, if people looking for an identity fixed upon ‘helpful’ as theirs.

Just imagine, for a moment, if people looking for an identity fixed upon ‘helpful’ as theirs.

It has the virtue of being unthreatening and unconfrontational. It is a position that one is not going to become an internet troll in order to defend. You won’t cancel people who are unhelpful. It is simply a way of being that helps us live harmoniously with others. It could also apply to the way we live in relation to the environment, and other species.

Helpfulness is a one-way process of generosity, but it is not something that is done in isolation. Nor does it require other people to respect it as an identity, since helpful people are not going to end up accusing others of being help-phobic. That would be a waste of effort that could be better spent – on being helpful.

Of course, adopting this as an identity would not be as simple as it may appear. Helping one person may be singularly unhelpful for someone else. Helping a mate rob a bank is hardly ethical. Nor is helping an institution with baleful intent – for example the armaments industry.

Helpfulness is not a solution to all ethical problems, but it can provide a trajectory.

Now it is only fair to mention something that the 2019 film glossed over. Mr Rogers was a Presbyterian Minister, and his television ministry encouraged a Christian morality, albeit without overtly trying to push Christianity.

As such, people inclined towards the progress narrative, and who think Christianity is a relic of the past, are going to see him as old-fashioned, and perhaps naïve.

Hopefully, by now, you will have gathered that I don’t think of wisdom as sitting within a novelty-driven paradigm, and in his very simple way, I think that Fred Rogers has managed to find a recipe for living that can be shared by people regardless of all their other points of difference (or even their personality types).

By focusing on the generous spirit involved in continuously recreating that helpful moment he makes it clear that the point of living is social and ethical.

Helpfulness is not an identity you can simply sit back and feel smug or superior about, because the moment you do that you are no longer being helpful. It is a self-policing identity that requires an ongoing effort of will-power to maintain.

In short, Mr Rogers transitions us from a focus on the politics of identity (with its undercurrent of power, ego and ambition) to the ethics of identity. And that, I think, is a very wise move.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.