The book that cemented my love of the past was called “People in History.” Its author, R.J. Unstead, was a teacher and prolific author of history books for young people.

My maternal grandfather gave me a copy of People in History when I was four and still living in an English village. Once I could read, I devoured its stories of heroes like Richard the Lionheart and knew many almost by heart.

It still makes a good read, but these days I cannot see it with the eager eyes of my childhood. The people in the book are predominantly male, and British. It is suffused with a spirit not only of achievement and heroism, but also of patriotic war-mongering.

It therefore amuses me to imagine who I would write about if I were to create an equivalent children’s book today. There are so many possibilities, but one person that would be high on the list is Elihu Burritt.

Odds on you will not have heard of Elihu Burritt. I only encountered him through researching the history of the clasped hands symbol as part of my PhD. From the late 1840s, Burritt used an image of a black hand shaking a white hand as his emblem – the only example of such a multi-ethnic handshake until well into the twentieth century.

From the late 1840s, Burritt used an image of a black hand shaking a white hand as his emblem – the only example of such a multi-ethnic handshake until well into the twentieth century.

I was further intrigued to discover he was a passionate campaigner for both peace and free trade. To my twenty-first century eyes, these two concepts felt mis-aligned. Politically, I associated peace activism with the left wing, and free trade with the right. Hence, I wanted to figure out how they could have been bedfellows in the nineteenth century.

Burritt was American. Born into an agricultural family, he became a blacksmith. By the nineteenth century, blacksmiths were expected to be literate, but Burritt’s passion for learning pushed him far beyond the limits of local libraries. He reputedly taught himself fifty languages, becoming known as the ‘learned blacksmith.’

He got involved in the Peace Movement in America, and then undertook a trip to the old enemy, Britain. There he walked around the country, often picking up work as a smith to pay his keep, and in six months managed to convince 50,000 Britons to sign a peace pledge.

He was a driver of the first great Peace Congress and created the “League of Universal Brotherhood” which aimed to establish peace and harmony between peoples across the world. He was an abolitionist, believing slavery to be inimical to brotherhood.

For Burritt, free, unrestricted trade between individuals (in the classic Adam Smith sense) was essential for ensuring that vested interests would not be tempted to use war as a mechanism for self-aggrandisement. He saw it as a way of encouraging peace and international goodwill.

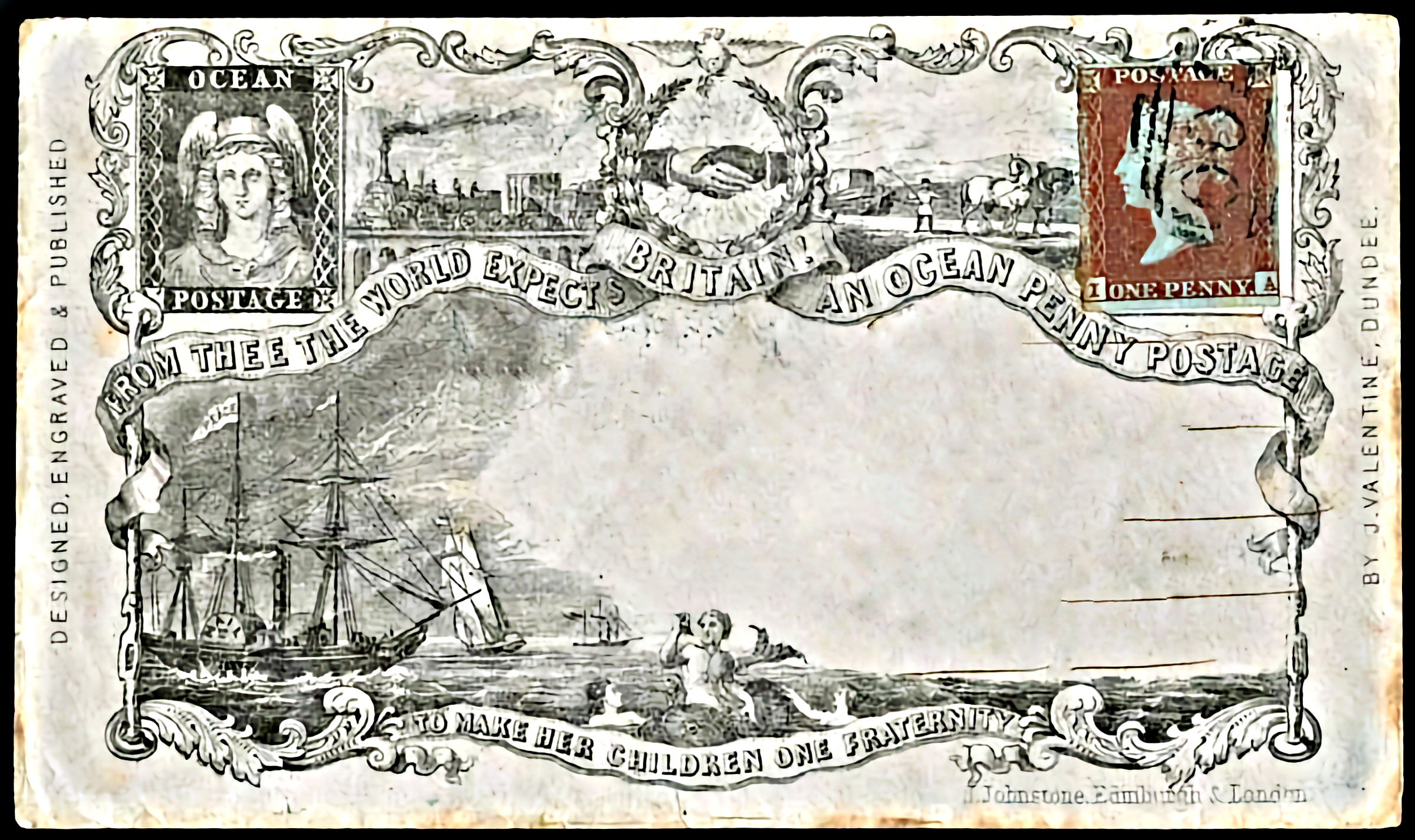

Another way of achieving such peaceful interaction between peoples was cheap international postage.

At the time, letters were expensive to send. That meant that poor emigrants, such as those who fled the Irish potato famine, could not afford to use the post – even if they were literate. Hence, they were barred from communicating with their families.

Cheap postage would, Burritt believed, alleviate this. All of these positions made him widely known and admired, and he would be appointed American consul to Birmingham (one of Britain’s largest commercial centres) by Abraham Lincoln.

I read a great deal of Burritt’s writing and found much of it inspirational. Here was someone who lived his convictions to the full. I certainly regard him as one of my heroes.

Yet even Burritt could not escape some of the attitudes of his time. Despite his clear hatred of slavery, he occasionally showed sympathy for the newly emerging Anglo-Saxonist philosophy which, in retrospect, was highly at odds with his other views.

Discovering these occasional jarring fragments made me reflect on how one deals with historical figures who almost all, when viewed from a contemporary lens, suffer from mud between the toes, if not fully-fledged feet of clay.

At University, my Ancient History lecturers tended to favour R.G. Collingwood’s approach to history. I gathered this to mean immersing yourself in the period you were studying to such an extent that you could understand it from the perspective of the people at the time.

By the 1970s, however, this was already a somewhat dated approach. More recently historians have tended to favour the idea that ‘the past is a foreign country’ – in other words unrecoverable in its original sense. Consequently, the point of doing history is to make sense of today, and we use the past to teach us lessons.

I cannot disagree with the newer approach. It is good to look at the past from a contemporary lens and see how we can improve on it. And yes, however much we attempt it, we can never completely see the past as it appeared to people at the time.

But I nevertheless remain uncomfortable with this newer formulation. We might look at Burritt’s use of ‘Brotherhood’ and object to its sexist language. Yet Burritt clearly intended to refer to everyone of all genders and races with his term. That was its usage at the time.

The fact that we can never fully know the past (or, indeed, another person) does not mean we shouldn’t try. It’s called having empathy.

The fact that we can never fully know the past—or, indeed, another person – does not mean we shouldn’t try. It’s called having empathy.

The term ‘conversational narcissism’ was coined relatively recently. It refers to people who have to turn every conversation back to themselves. It is a useful reminder to take into account the perspective of others if you want a genuinely shared connection.

While a conversation can never be a complete analogy for the practice of history (for the past cannot reply) I think there is something to be said for trying to listen to what the past is trying to say to us on its own terms, rather than imposing our own attitudes.

It would be so easy to write Burritt off on account of a few ill-chosen phrases. Yet that would be to miss a truly remarkable person who still has much to say to our contemporary situation.

To deal with this conundrum, I created a yardstick to help me do justice to people from the past. I try to understand what was legally defensible, morally defensible and socially acceptable at the time.

I try to understand what was legally defensible, morally defensible and socially acceptable at the time.

These goalposts have moved significantly even within my lifetime. Some things that were taken for granted in the 60’s and 70s are now considered reprehensible.

Yet, while it is good to see our attitudes getting more finely attuned over time, I think that we should not judge historical individuals too harshly if they ticked all three of my boxes. We can object to their actions or words in retrospect, but we should still be able to acknowledge them as decent people according to their own society’s lights.

The future will no doubt look at us and find our actions wanting. Things we take for granted will no longer be so. We can only hope that the future will be more generous to us than some of us are to figures from our past.

I found heroes in my childhood book. Some of them, like Richard the Lionheart, probably didn’t deserve that adulation. But I still suspect that having heroes from the past is a better route to wisdom than, for example, listening to contemporary influencers. Just don’t expect historical heroes to look good in every possible lighting.

Still, a few metaphorical wrinkles should not put us off being inspired by people from history. People like Elihu Burritt.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion