By 7:00am I was on the bus. Throughout my career I had a thirty-minute bus journey in the morning to reach my work and a longer one home at night.

In the mornings, I would cross Auckland’s Harbour Bridge at around 7.20. The bus would then drive past Victoria Park, and on into the city.

As we went past the park, we would start to see them. Scantily clad people jogging through the early morning chill.

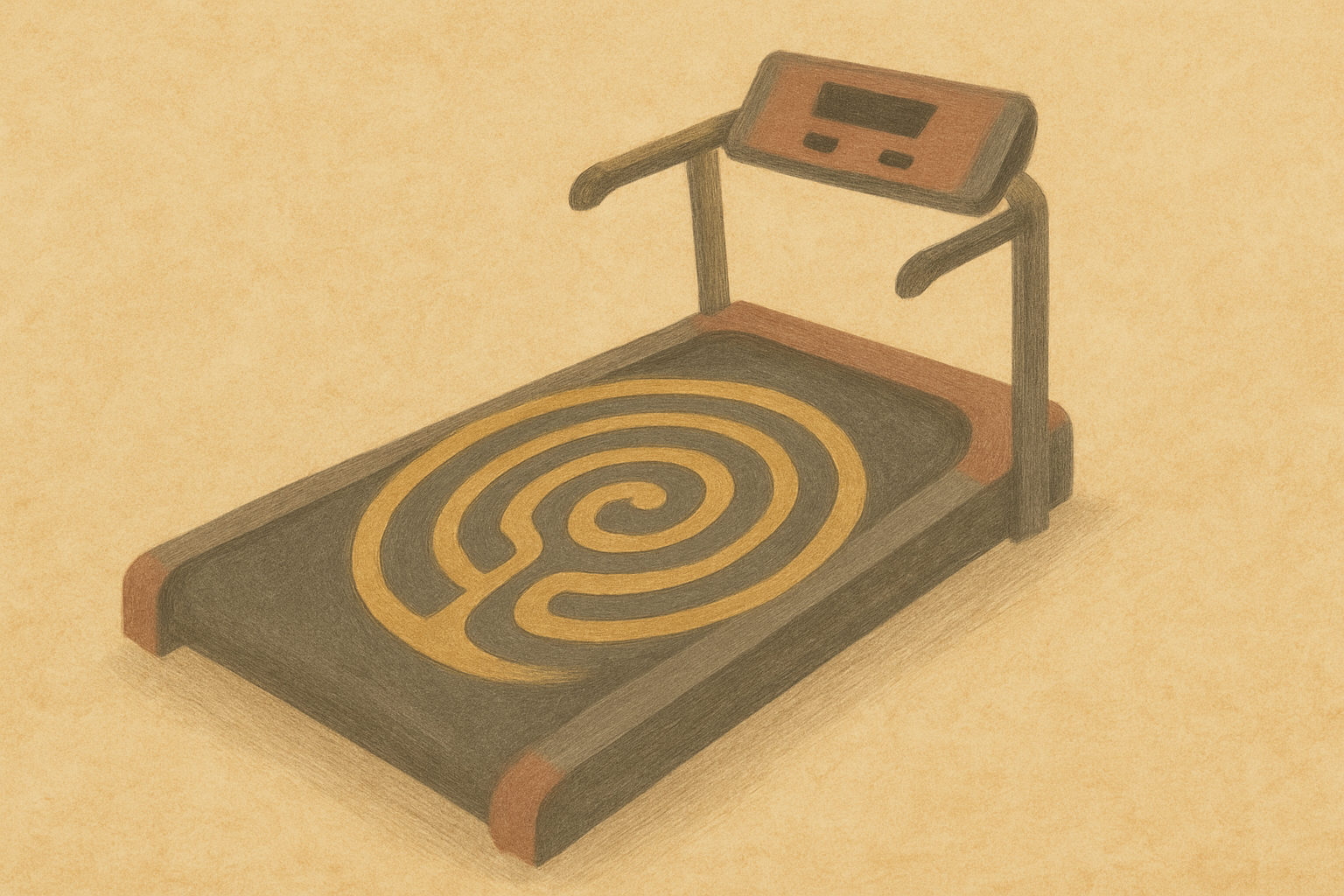

The bus route passed one of the country’s largest gyms and the nearer we got to it the more people we saw sweating their way in its direction. No doubt when they arrived there, they would start comparing times and perhaps discuss the latest Iron Man event they took part in.

Sitting on that bus, it struck me that, had I been living five hundred years ago, these same people would have been the ones heading off for early Mass, grasping their Rosaries and discussing their latest pilgrimage.

There is a certain type of person that cares deeply about health. Five hundred years ago it was the health of their souls that mattered. Now it is the health of our bodies.

Five hundred years ago, these same people would have been heading to early Mass. Now it’s the gym.

And in both cases the activity attaches itself to a certain kind of moral superiority. Going early to church back then, and going early to the gym now, are symbolic of health, but the extra effort involved carries connotations of virtue.

Don’t get me wrong. There would have been people who found genuine spiritual solace in their early morning church attendance, just as there are people who gain lasting health benefits from racing the dawn to get to the gym.

But I suspect that sometimes the activity carries a large dollop of performativity, too. It’s about looking good – in both senses of the phrase.

While a congregation can help keep you focused, you can realistically say an early morning prayer in your own house, and exercise at home too. The results are much the same. But without the symbolic optics, you receive no external validation for it.

You can pray at home or exercise at home — but without the symbolic optics, you receive no external validation.

Symbols are tricky.

Our society uses less overt shared symbolism than we once did (if we discount the constant reminders of brands that surround us). Even use of the term ‘status symbol’ has fallen away.

Now we seem to prefer do-it-yourself symbol-making, even if we don’t always recognise it as such. The way we talk, the way we dress, what we drive and what we eat can all symbolise something. And that is just for starters.

But because these symbols are often personal, the potential for them to clash with others seems greater than ever, especially when you add social media and its performative optics into the mix.

In such environments language is particularly prone to problems. Certain words can become laden with symbolism. Look at how the colours white or black can piggy-back all sorts of other meanings.

Some of my least pleasant experiences have occurred when I used a word the way I understood it, only to discover that the person I was talking to attached a different symbolic meaning to it.

I now recognise that if someone (including myself) is reacting disproportionately to something that has been said, then I need to look for an embedded symbol. It is usually there.

When someone reacts disproportionately to a word, I’ve learned to look for an embedded symbol. It’s usually there.

I have an ambivalent relationship with symbols. In general, I would prefer to deal with things purely at face value. Nevertheless, there are times when we need something small to take us somewhere large – things that symbolically remind us of our hopes, duties and obligations.

But, regardless of the symbols we choose, it would be nice if they could lift us towards something genuinely important and not simply be a quick way of gaining approbation.

As far as I know, there is no step-counter calibrated to moral worth.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion