"The lament for a dead child, the demand for justice, the lover’s yearning for his beloved – before our recognition of the universality of human emotion, time and distance shrink, the barriers of language, color, and nationality go down; we look into the mind of a man three millennia dead and call him 'brother.'"

Thus concludes the best book on Ancient Egypt you will ever read: Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs: The Story of Egyptology. Barbara Mertz, its author, neatly summed up, in 1964, what draws me back, time and again to history.

It’s not the politics, the great leaders or the momentous events. It is that recognition that people thousands of years ago, in cultures distant to our own, experienced death, disappointment, triumph, envy, love and all the human emotions and drives that we exhibit today. The cultural trappings within which they are framed change drastically, but underneath it all, the same human themes repeat.

The cultural trappings within which they are framed change drastically, but underneath it all, the same human themes repeat.

Mertz’s own story is something of an object lesson in the human capacity to build triumph on top of disappointment.

Fascinated by Ancient Egypt from an early age, she completed her PhD in 1952 but was unable to find an academic position and spent the next few years doing secretarial work. Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs was her first book. It is brilliantly written, at times very funny, and, when writing about Egyptologists, she was quite happy to skewer silliness when she spotted it.

It was a breath of fresh air, and I fell in love with it when I came across it by chance while doing my Masters in Egyptology. And I couldn’t understand why no-one ever recommended the book to students.

The tale I got from one of my lecturers, when I asked him about this, was sobering. He said that everyone knew that it was a good book, but that Mertz was persona non grata because when someone close to her did his PhD defence, it became apparent that he hadn’t written parts of it. The inference was that she had written it for him.

Unfortunately, this type of scuttlebutt could have very real consequences. In academia, at that time, reputation was everything, and a story like this, regardless of its truth, was enough to ruin a career. These days we would call it getting cancelled.

In academia, at that time, reputation was everything, and a story like this, regardless of its truth, was enough to ruin a career.

Mertz herself ascribed her inability to find an academic job to male chauvinism, and that is very likely. Whatever the truth of the matter, her lack of affiliation to any academic institution had the upside of freeing her to write in the way she wanted to.

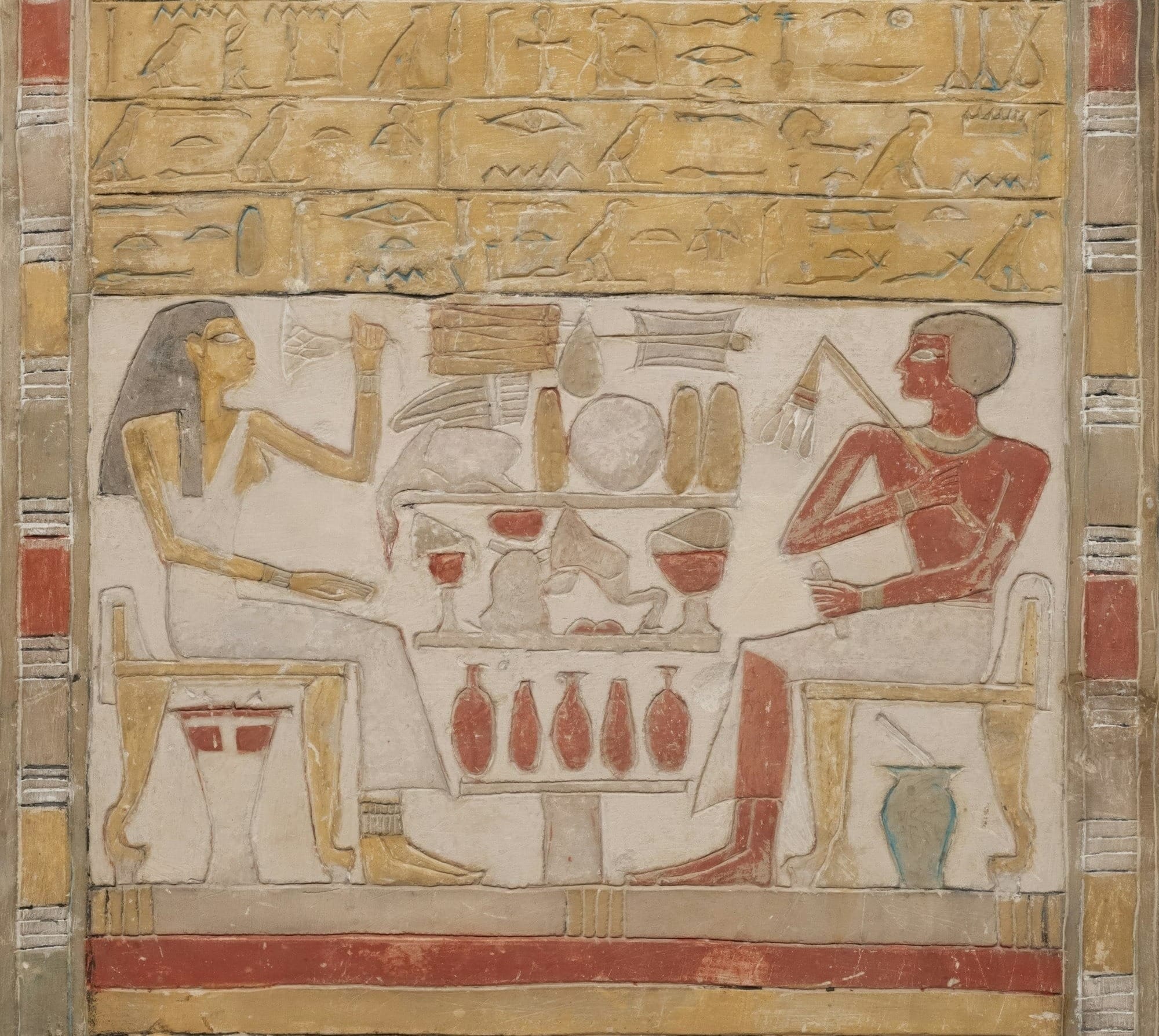

Her next book Red Land, Black Land explored Ancient Egyptian daily life. My favourite part is her section talking about the family of Heqanakht (she spells it more how it sounds: Hekanakhte).

This patriarch was a priest who lived nearly four thousand years ago. His job took him away from home, and he wrote a number of letters back to his eldest son, Mersu, telling his hapless heir how to deal with things in his absence.

Sometimes practical, these missives not infrequently involved sorting out the family feuds and gossip that had reached the fatherly ears, presumably via letters from various tattling family members.

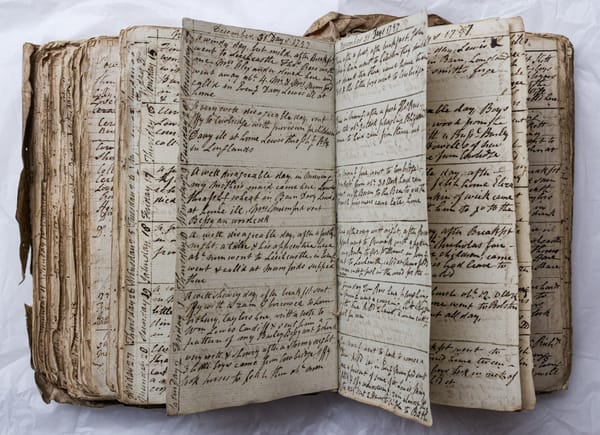

Mersu sometimes took his father’s letters into an empty tomb to read them in peace and then discarded them. These were later buried in tomb debris and discovered in the 1920s. The letters are one of the best, and most complete, windows into ordinary life in an ancient culture, and were the inspiration for Agatha Christie’s murder mystery Death Comes as the End.

Should you Google the Heqanakht letters, you will find lots of fairly prosaic discussion of the letters’ significance. Read Mertz and you are drawn into the family’s life.

"One would think that Hekanakhte had troubles enough with his quarrelsome brood of children and dependents, but he did not know when to leave well alone. He never mentions a wife, so presumably he is a widower. In a burst of elderly vigor he decided to take a concubine,1 and this damsel destroyed what little peace was left in the household… [She] managed to irritate everybody. Hekanakhte ordered his son to fire one maid who had threatened or offended the girl; he warned Mersu against the third son Sihathor, too."

Without straying from the evidence she had to hand, Mertz is able to bring the letters to life and give them colour. And clearly her love for character and story won out in the end. Red Land, Black Land was her last academic book. From then on Mertz would become a novelist – and a successful one – under the names Barbara Michaels and Elizabeth Peters.

In the latter guise, she wrote a series of twenty novels, set between the 1880s and 1920s, following the career of Amelia Peabody, a female Egyptologist. These allowed Mertz to live her Egyptological dreams vicariously, and to involve the heroes and villains of the early Egyptological community.

I suspect that the reason that Mertz so enjoyed writing about the petty jealousies, backstabbing, grandstanding, finger wagging and whining that goes on in the Hequanakht letters is that it bore no small resemblance to life in academia. And Mertz rose above and beyond it.

I suspect that the reason that Mertz so enjoyed writing about the petty jealousies [...] in the Hequanakht letters is that it bore no small resemblance to life in academia.

History is great for getting a glimpse into human foibles and frailties, but it can also provide heartening examples of people overcoming the odds. Mertz demonstrates that to the full. Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs is still in print (in a revised and updated form) where most other histories of Ancient Egypt have disappeared into back catalogues. It remains a read for the ages.

1 More recent translations of the text suggest that this lady, Hetepet, was actually a new wife. Either way, she was the inspiration for the much-despised murder victim in Christie’s novel.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion