One of the side-effects of the pandemic has been a concerted campaign to stop people shaking hands. Fist bumping was suggested as an alternative. Yet while there is no doubt that shaking hands is less hygienic than fist bumping, I wonder whether hygiene is the only measure we should be thinking about? What about its meaning?

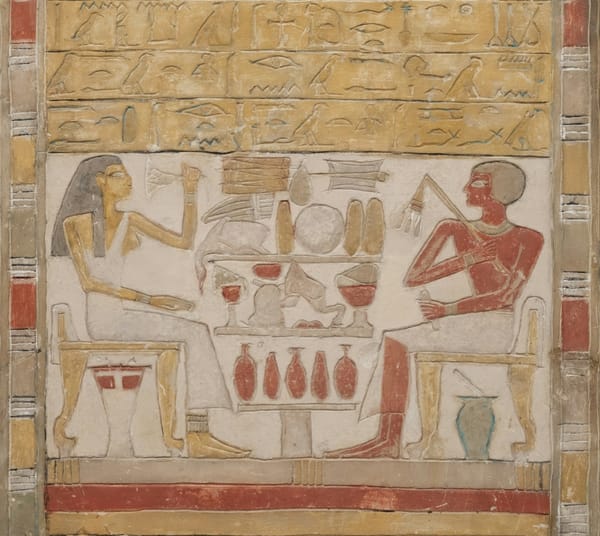

The earliest examples of handshaking, which date back over two millennia, were not actually about greeting. Rather, they symbolised trust and became associated with sealing some kind of deal – such as a peace treaty or marriage vows. Over the centuries, there were many subsequent usages, including as an alchemical symbol for the fusion of opposites and shaking hands at New Year.

There are hints, as early as the fourteenth century, that some everyday people greeted one another by shaking hands, but in general, greetings in Europe remained primarily non-contact over the next four centuries. Curtseying, bowing and doffing your hat were the norm – a system whose etiquette embedded deference to those who were your social superiors.

Curtseying, bowing and doffing your hat were the norm – a system whose etiquette embedded deference to those who were your social superiors.

Handshaking, by contrast, is a potentially invasive gesture. It involves touch. Hence, it initially occurred only among equals. During the eighteenth century and earlier, trying to shake your superior’s hand would not have ended well.

Later history categorises the "greeting" handshake as an English invention. Protestant groups like Quakers (who insisted on shaking hands with everyone and not doffing their hat to anyone) may have spread it via their business dealings.

And Britain’s early industrialisation and growing cities created an environment where meeting strangers occurred more frequently. Having a common form of greeting, in this context, made sense.

But behind it, too, lay the radical concepts of liberty, equality and fraternity emanating from France and America. Being able to shake hands with any fellow citizen carried strong connotations of equality.

Being able to shake hands with any fellow citizen carried strong connotations of equality.

Consequently, when you shake hands, you are perpetuating a concept that goes hand in hand with Western liberal democracy and its citizenship – one that states that people have equal rights, and that when you shake hands, you are acknowledging this. That’s what made Elihu Burritt’s interracial handshake so radical in the 1840s.

It is therefore sad that we could be at the point of abandoning a practice with such a rich history – precisely because we have no idea what we are letting go of. Surely, asserting our equality remains an important statement in a western world that seems fixated on liberty, but is fast losing equality and fraternity.

In the end, the handshake debate rather effectively demonstrates the distinction between being sensible and being wise. The sensible course here is to ditch the handshake in favour of a more hygienic alternative. However, ignoring its history and symbolism does not, to me, seem wise.

The Flirting with Wisdom series has neither sought nor achieved a consensus on what wisdom is. Were I pressed to come up with a definition, it would be ‘distilled learning and experience.’ However, this sounds like I’m saying that wisdom is something tangible, and it isn’t.

Instead, wisdom seems to me to be more a process than a destination. In a constantly changing environment, wisdom is never entirely fixed or immutable. How it appears is inevitably dependent on your vantage point.

In other words, wisdom is not a trophy to be hunted and then hung up on a wall or put on a pedestal. Neither is it a rare thing to be collected, pinned, labelled and hoarded. Wisdom of those types is already dead.

Rather, it exists in a constant state of rediscovery, where each iteration looks a little different, and every time you think you have it, it fades and slips between your fingers. With wisdom, we have to be happy to remain seekers, rather than finders.

Wisdom is not cemented into overarching schemes. Instead, it is collaged together from the details of our lives. And while passion may be found abundantly at the extremes, if wisdom has a direction, it is towards the centre, towards that point where two hands, still distinct, touch – and communion begins.

… if wisdom has a direction, it is towards the centre, towards that point where two hands, still distinct, touch – and communion begins.

Though such moments of wisdom may be fleeting, I would nevertheless encourage people to share them as generously as possible, trusting that they may be of use. Will they speak to other people? Maybe to some, and not to others. We are not all identical, and we respond to things differently. But we won’t find out unless we reach out and share.

And that, in a very small way, is what I have tried to do in this series.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion