Many people I know believe there is no such thing as Truth.

They state this as a fact. Anything that passes for truth is simply ‘culturally or biologically conditioned’. Talking about truth is therefore unnecessary.

That may be, but is actively avoiding thinking about Truth wise?

My father was an artist. Accepted into London’s Slade School of Art at sixteen, throughout his life he measured himself against his artistic hero, Cezanne.

The first time I saw an original Cezanne (in the Getty Museum in 1975) he taught me how to look at it. “Stand here”, he said. The picture was beautiful. “Now take a step back”. I did, and the painting dissolved and became a whole new work. “Take another step back”. Again, the painting changed before my eyes.

“You can’t appreciate a Cezanne from a photograph.” Dad said. “It only ever shows one of the versions of the painting. A good Cezanne is half a dozen paintings in one. You can see why he painted so slowly. Every stroke had to work in multiple ways.”

A good Cezanne is half a dozen paintings in one.

Living in New Zealand, you don’t get to see many original Cezannes. Hence, when I was teaching art history, I had to make do with reproductions.

One day I was reading through a book and looking at some of the many versions of Mont Sainte-Victoire that Cezanne painted. Cezanne was obsessed with his local mountain. He painted it frequently, from many different vantage points.

And every time he painted it, it was different.

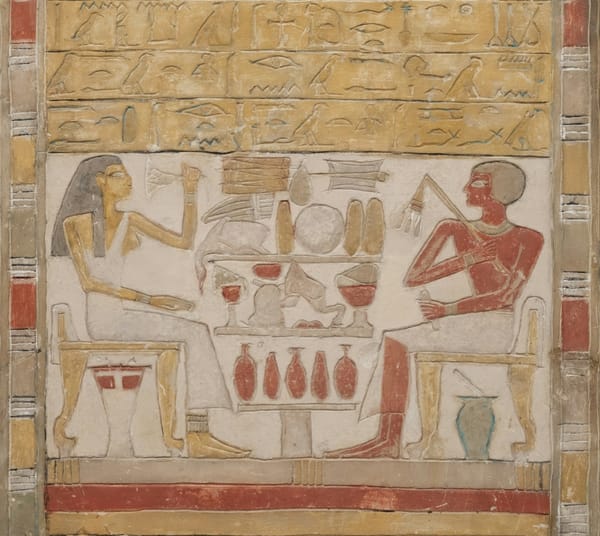

The craggy shape gave endless variations. It was then that I made a connection. Thinking of Truth as if it were Mont Saint-Victoire, and us as Cezanne, helped resolve the tension between Truth-as-absolute and Truth-as-relative. The mountain was undeniably there, changing only slowly as wind and rain weathered it, and vegetation sprang up. But how it appeared was relative to where one stood.

In other words, Truth was not going to look the same from different perspectives, but it was still there, like Mont Saint-Victoire, solid and waiting to be discovered.

Thinking about Truth in this way changes truth-seeking from a static to a dynamic process.

We are always moving – most particularly through time. This means that, just as Cezanne kept trying to rediscover Mont Saint-Victoire, we keep rediscovering Truth, in whatever new context we find ourselves in.

Just as Cezanne kept trying to rediscover Mont Saint-Victoire, we keep rediscovering Truth, in whatever new context we find ourselves in.

We can try and capture that blinding moment of Truth in writing, art or whatever, but we have to expect that those static images will gradually become less true over time. Some faster than others.

I suspect wisdom functions in much the same way. It is a process of ongoing search and discovery.

In writing down some of what I have discovered over time, I hope that parts of it may resonate with readers. I would be foolish, however, to frame it as eternal Truth, or even as original. Most wisdom has been discovered again and again over centuries. Instead, any insight I may have is simply my sense of truth in a given moment, and it does not excuse you, the reader, from doing the hard work of seeking out wisdom from your own experiences. What I’m doing here is more about modelling a process of attentiveness than delivering a short cut to achieving wisdom.

My father travelled with Cezanne by his side for his whole life. I am not asking such dedication of you. However, this series documents my meandering journey around the mountain, and I hope you have now seen enough to continue with me on this trip.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion