In the 1780s, Josiah Wedgwood, the leading ceramicist of his day, had a problem. How could he best promote his highly innovative manufacturing?

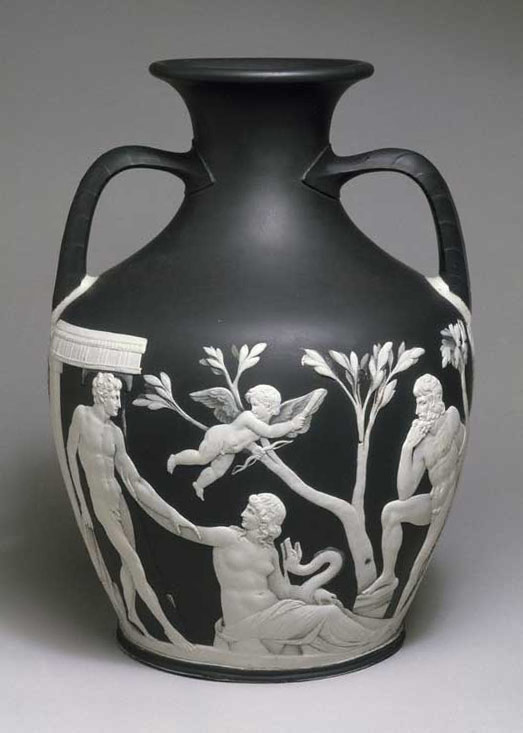

His solution was not one we would use today. He opted to attempt a reproduction of a Roman vase.

Wedgwood was living in the age of Neo-Classicism where value was attained through reference to the past. He chose this particular vase because it had become a sensation when it was brought to England in 1783.

Known originally as the Barberini Vase (but subsequently, after the Duchess of Portland bought it, as the Portland Vase), it remains the most advanced piece of Roman cameo work ever found.

Wedgwood took five years to translate this Roman glassware into ceramics and he had to invent a series of new processes to do so.

Yet, in the 1780s, novelty had not yet become the selling point it is today.

Wedgwood’s contemporaries were less excited by Wedgwood’s innovations than by how his version of the Portland Vase equaled the efforts of the Ancients.

Novelty’s value, however, would soon increase. By the mid nineteenth century advertisers were trumpeting ‘novelties’ of all kinds. The industrial revolution and consumerism changed people’s attitude to tradition.

From trying to match the ancients, society transitioned to a world that embraced a narrative of novelty and the thing it symbolizes – progress.

From trying to match the ancients, society transitioned to a world that embraced a narrative of novelty and the thing it symbolizes – progress.

In this new world, the urge to embrace novelty carries an equivalent urge to ditch the old. Things that are ostensibly working fine must be ‘disrupted’ to make space for novelty to take over. AI is just the latest in a long line of novelty-driven crazes.

The ‘progress narrative’ that we now take for granted assumes that change is necessarily for the better, but it is worth asking whether this is really the case?

Do the changes that occur via progress actually bring societal improvement?

Let me give you an example. When I was a young teacher, just starting out, novelty was located in video tapes. Film reels and projectors were now regarded as old-school, as was classroom teaching. In the future, according to its advocates, students would learn from videos, rendering teachers and classrooms redundant.

Over my career, this narrative has remained largely unchanged, except that it has attached itself to a progression of new technologies – first CDs, then the web, then blogs and podcasts followed by online education and now AI.

So has education improved much as a result of all this technological disruption, and the gazillions of dollars invested in it? Sadly, I just can’t see it.

Experiences like these have made me particularly wary of the way that we have conflated progress with technology. Granted, there seems to be an industry of futurists talking up whatever version of the future is going to increase the power and profitability of large tech companies, but do we have to listen to them?

Aren’t there better venues for progress – like ecology or ethics?

Aren’t there better venues for progress – like ecology or ethics?

Call me old and cynical, but nowadays I opt to ignore anything new until I can see that it will make a clear improvement in people’s lives.

I don’t buy the hype and I don’t want novelty for novelty’s sake. While I am happy to let younger folk explore novelty for themselves, I prefer to wait for the novelty value to wear off, so I can see if there are any enduring benefits. If there are, I’m in.

But in the meantime the familiar, for all its imperfections, suits me fine. My tea still tastes perfect out of Wedgwood china.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion