What does it mean to live on Earth as if we want to stay?

It’s a beautiful question — one that lingers in the mind and takes root in the heart. It invites us to reimagine what life is for, and how we might relate differently to the world, each other, and ourselves.

This article began as a Grok Talk — a Grokkist gathering where longtime systems thinker and cultural evolutionist Mike Nickerson shared stories drawn from decades of practical work in sustainability and social imagination.

What follows is a lovingly adapted version of Mike’s talk — not just a recording or transcript, but a narrative re-telling in his voice and rhythm, shaped for reflection and re-use.

▶️ Prefer to watch? Jump to the full video recording

📖 Like stories? Read on for a prose adaptation of Mike’s talk

🔗 Want to go deeper? Explore curated resources, references, and rabbit holes

📅 Feeling grokky? See upcoming Grok Talks and gatherings

At Grokkist, this is how we roll: we gather, we listen, and then we turn what emerges into something enduring and shareable — so the conversation keeps travelling.

Watch the Full Recording

Or if you prefer to read — we’ve adapted Mike’s full talk into a warm, narrative form below. It’s not a transcript, but a story. One you can revisit, share, or sit with in your own time.

From Curiosity to Coherence

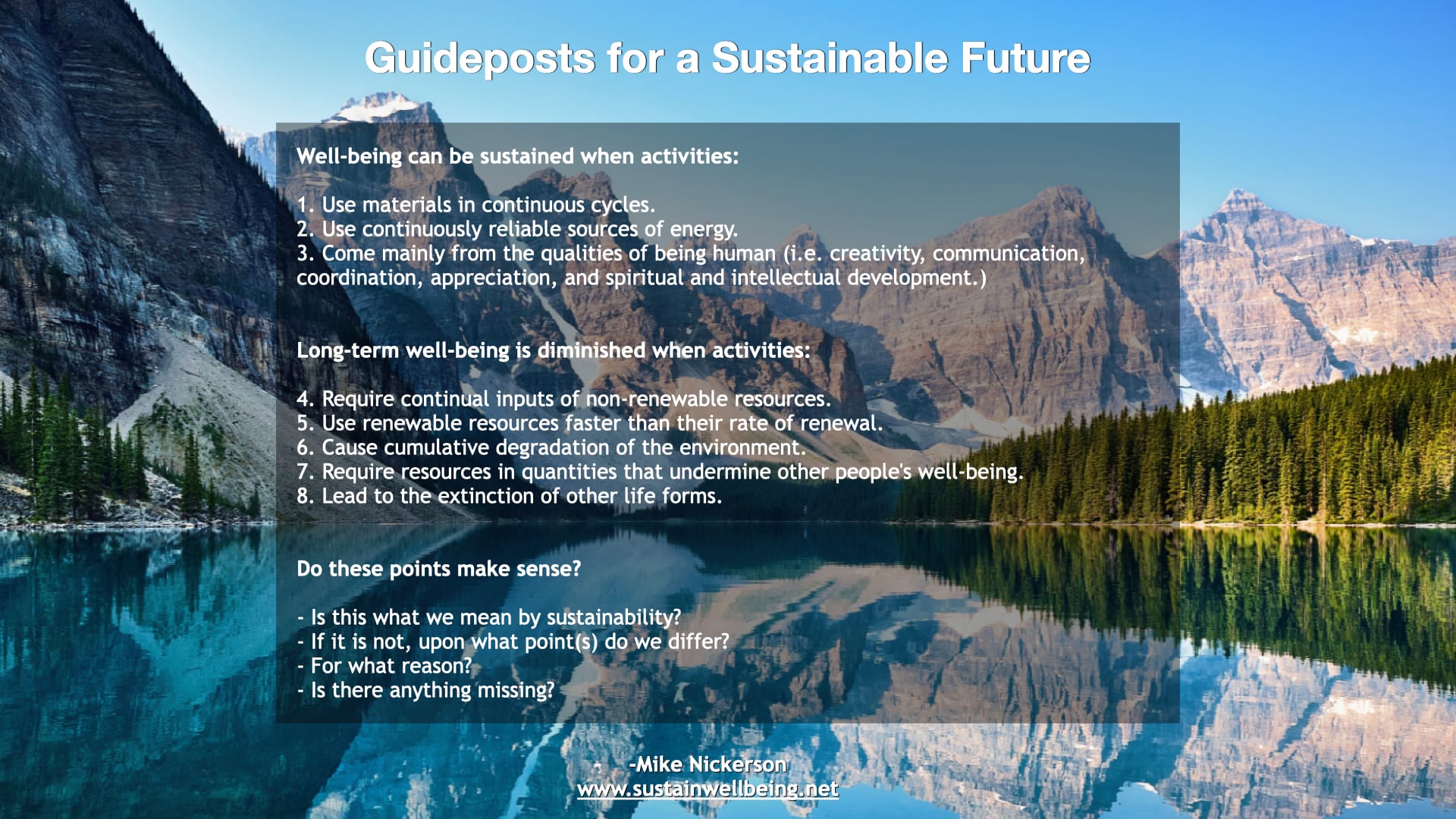

What you’re seeing there — “Guideposts for a Sustainable Future” — that’s the only slide I brought. It’s a simple outline, but it comes from a long journey.

I first started thinking seriously about sustainability — although we didn’t call it that back then — when I was in my late teens. I had this moment where I realised: I’m human. I can observe, absorb, think, and express. So what am I going to do with that? What needs doing?

That question led me to hitchhike across Canada and down the west coast of the U.S. I’d turn up in libraries, dig through community directories, and find people doing voluntary or not-for-profit work. I’d call them up and say, “I’m interested in what you’re doing. What do you know?” More often than not, they’d invite me over. We’d talk. They’d tell me what problems they saw and what solutions they were trying out.

I did that for months. City to city. Conversation to conversation. And then I came back to Toronto, where I met a group of young people also working on peace and environmental issues. We formed something called the Institute for the Study of Cultural Evolution — mostly just a banner for our curiosity. Eventually, a few of us moved to Ottawa. Twenty of us across three rented houses, all in our twenties and early thirties, sharing books, meals, and ideas.

We hoped to build something like what we now call an eco-village — though that term didn’t exist yet. We didn’t have the money. We could barely pay rent. But we learned a lot.

When the group disbanded, I took all the notes from those years and started sorting them into piles. This thing over here, that thing over there. Eventually I wrote a sentence to summarise each pile — just to make sense of it all.

And that’s what you see on the slide.

A friend looked at it about a year later and said, “This is a definition of sustainability.” This was in 1974, before the term had much traction. But it stuck. And it made sense.

What I’d come to understand is that the impulse to care — to notice a problem and want to make it better — is society’s natural immune system. Some people see something wrong and just quietly start working on it. Sometimes they solve it. Sometimes they talk to others, build organisations, lobby governments. It’s all part of a larger healing process. That’s where these guideposts come from: years of listening to people who were already trying to make things better.

The impulse to care — to notice a problem and want to make it better — is society’s immune system.

Now, I’m sure you’ve heard the old line: Give a person a fish and they eat for a day. Teach them to fish and they eat for a lifetime. But here’s the catch: if you teach everyone along the shore to fish, you might collapse the fish stock.

That’s a sign of a deep shift in our relationship with the Earth. For most of human history, if you wanted more of something, you just worked harder. More people, more tools, more time — and you got more. But now, the limit isn’t effort. It’s the capacity of the system itself.

It’s not just fish. You can’t extract more timber just by sending in more machinery. You can’t pump more oil forever. You can’t draw more fresh water than nature can replace. At some point, you hit the edge of what’s sustainable — and you have to work within it.

That’s the real lesson. And it’s not an easy one to learn — especially if you grew up in a culture where you could always ask for more and usually get it. But we’re at a point now where it matters very much what we do. For a long time, we were like young offenders — small enough that our actions didn’t really make a dent. But now? We’re strong enough to break things. So it’s time we take adult responsibility.

The Laws of Nature and the Trouble with Growth

So here’s the thing — once we’re big enough to make an impact on the planet, we become subject to the laws of nature. And really, there are only two that matter.

The first is the law of the minimum. It’s about what’s available compared to what we need. You can have everything else lined up — all the resources, all the plans — but if one critical thing is missing, that’s the limit. You can’t go past it.

There’s a great example of this from New Zealand. Sheep were growing just fine, but they weren’t reproducing. Turns out the soil was missing cobalt — just a trace element, but essential. Once they added it back in — either through the feed or the soil, I can’t remember which — the sheep started reproducing. That’s the law of the minimum. You only need to be missing one thing, and everything stops.

The second is the law of tolerance. That’s about how much of something can be endured. Think about yeast in fruit juice. Yeast digests the sugar and creates alcohol. As the alcohol level rises, it eventually hits about 14 percent — and that’s it. Yeast can’t tolerate any more, so it dies off. You’ll never find naturally fermented alcohol stronger than 14%. Anything beyond that has been distilled or altered. There’s a hard upper limit to what can be tolerated.

So those are the two constraints we live within: how little we can do without, and how much we can put up with. That’s the bracket we’re inside. If we can learn to live within those boundaries — the law of the minimum and the law of tolerance — we can be fine.

There are the two constraints we live within: how little we can do without, and how much we can put up with.

If we can learn to live within those boundaries — the law of the minimum and the law of tolerance — we can be fine.

But we’re not acting like that. We’re not a species of young offenders anymore, where our actions didn’t have consequences. We’re grown now. We’re powerful. And the laws of nature will hold us accountable — not in a courtroom, but in the slow, implacable justice of natural selection.

That’s really what most environmental problems come down to — they’re either resource problems or waste problems. How much we need, and how much we can afford to discard. It’s that simple. That’s just the coordinates of being a creature on this planet.

But here’s where things get trickier.

We live in a world that’s hooked on growth. Practically every country on Earth — maybe with the exception of Bhutan or Costa Rica — is trying to expand economic activity all the time. And that’s a problem when we’re already pushing up against planetary limits.

How do you get a civilisation that’s been growing for ten thousand years to realise it’s grown up now? That more isn’t the answer?

That’s what my work has really been about — drawing attention to that question of direction. And that’s where More fun, less stuff came from.

You can’t really take sustainability seriously unless you understand that this growth thing has hit a wall. But the problem is, most people haven’t clocked that yet. They see systems as something outside themselves. If things aren’t working, they just double down. Try harder. Push more.

So More fun, less stuff became a kind of meme. Something simple enough to catch people’s ear. It slips in through the side door, gets stuck in their head. And then maybe, just maybe, it opens up space for a bigger reckoning.

Because the truth is, we have to move away from measuring success by expansion — by how much we produce, how much we consume — and toward a different kind of richness. One that comes from living well, not living big.

We have to move away from measuring success by expansion — by how much we produce, how much we consume — and toward a different kind of richness.

But our system doesn’t really allow that. It’s set up in such a way that if it doesn’t grow, it gets sick. We call it a recession. Or a depression. Growth isn’t just encouraged — it’s required.

And that’s where the tension lies. Between what we’ve built… and what the planet can bear.

How Money Works (And Why It Doesn’t)

You know, one of the best ways to understand why our economic system keeps demanding more is to look at how money actually comes into circulation. Most people never think about it — which is a bit wild, considering how central it is to everything we do.

But before we get into that, let me tell you a little story.

The Cowboy Parable

Four cowboys have been out on the range all day. They’re hot, dusty, and ready for a good time. So they head into the bar, order their beers, and ask the bartender if they can borrow a deck of cards to play a few hands.

The bartender says sure. He gives them a full deck — 52 cards — and deals out 13 each. Then he says, “At the end of the night, I want each of you to give me back 14 cards. One extra for interest.”

Now, if you’re good at maths, you can see where this is going. There aren’t enough cards in the deck for everyone to pay back what they owe.

That’s the money system.

The Problem with Debt-Based Currency

When money is created, it’s almost always created through loans. Only about 3–4% of the money in circulation exists as physical coins or bills. The rest? It’s just numbers — entries on a digital ledger somewhere.

Let’s say you’ve got a great business plan and you need $100,000 to make it happen. You go to the bank, they like your pitch, and they give you a line of credit. That money didn’t come from a vault. It came from a keystroke.

You spend that money — hire people, buy materials, rent a space. It goes out into the economy. Other people spend it again. It circulates.

But when it comes time to repay the loan, you don’t owe $100,000 — you owe $110,000, say, with interest. And here’s the kicker: that extra $10,000 was never created. The system assumes someone else will borrow that money into existence so you can earn it.

So if the economy doesn’t grow — if more loans aren’t taken out to pump more money into the system — someone somewhere can’t pay their loan. They default. Businesses go under. Recession hits. And that’s considered normal.

Imagine: we produce more goods and services this year than at any point in history. But if next year we only match that level — not even dip, just stay the same — we call it a downturn. That’s not a great way to run a society.

Why Do We Borrow from Banks?

You might ask, why does money have to be created as debt? Why can’t governments just issue it themselves?

They can. Most constitutions include the government’s right to create currency. But at some point — through pressure or ideology — governments decided to outsource that power to the banks. Now, instead of creating money for public use, they borrow it… and pay interest.

But there are other ways. One is to simply spend money into existence through public works — infrastructure, health, education. No debt. No interest. Just energy flowing.

A Tale of Two Economies: Wörgl and the Stamp Scrip

There’s a story I love from Wörgl, a small town in Austria after the First World War. The economy was in ruins. People had time and skills, but no money. So the town created its own local currency — a “stamp scrip.” You had to pay a small fee to keep it valid, like a stamp every month. So the longer you held onto it, the less it was worth.

Naturally, people spent it quickly. It circulated. Buildings were repaired, streets were paved, agricultural land was improved. While the rest of Austria languished in depression, Wörgl was thriving.

They found that money in Wörgl changed hands 14 times more often than in the national economy. And it wasn’t the money doing the work — it was the people, inspired to take action, to make and trade and build. That’s what creates community.

There are still local currency projects today. They tend to pop up during hard times — recessions, downturns — when people have more time and fewer opportunities. They don’t always last, but they show us something important: we don’t have to be enslaved to a system that only works by increasing debt.

Blood, Barter, and the Body of Society

Money is a useful thing. Incredibly useful, in fact. If you try to run a barter economy in today’s world, it gets complicated fast. The odds that someone needs what you offer and has what you need? Slim.

Money simplifies that. It acts like blood in the body. Just as blood carries nutrients between organs, money circulates value between people — from farmers to teachers to builders to musicians. It integrates society.

But debt-based money? That’s the problem. Because it demands exponential growth, and exponential growth doesn’t work in a finite world. The money grows faster than the forests, faster than the fish, faster than anything that actually matters.

That’s what leads to hard times. Not laziness. Just bad design.

From Capital to Consumption

It’s worth saying: capital accumulation didn’t start as a bad thing. In the early days of industrialisation, capital was used to build things — looms, factories, tools. It lowered costs and raised access. Clothing became cheaper, food more abundant, tools more available. In that sense, wealth was a reflection of value created.

Back then, if someone was rich, the assumption was they’d provided a lot of goods or services to society. That’s the logic behind Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” — the idea that by acting in your own interest, you could end up benefiting society as a whole.

But by the 1920s, something had shifted. Industrialisation had largely met humanity’s basic needs — at least in the developed world. Instead of celebrating that, we started manufacturing new wants. Creating desire.

There’s a quote I often share from a retail analyst:

“Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life… That we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals… That we seek spiritual and ego satisfaction in consumption… That we need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever-increasing rate.”

It’s staggering. And heartbreaking. We’ve become very good at waste — and the consequences are catching up with us.

I used to think the end would come from running out of fossil fuels. But with fracking, tar sands, deep-sea drilling — it’s clear there’s no shortage. The problem isn’t supply. It’s the waste products. Climate change, pollution, ecological collapse. That’s the real wake-up call.

Reduce, Reuse… Recession?

You’ve probably heard the three R’s: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. They’re a good start. But it’s been interesting to watch how those priorities got reshuffled.

These days, “reduction” and “re-use” are downplayed. Why? Because they slow the economy. If people consume less or re-use more, companies sell fewer products. And that means recession.

These days, “reduction” and “re-use” are downplayed because they slow the economy.

If people consume less or re-use more, companies sell fewer products. And that means recession.

Recycling, though — that’s okay. You can build businesses around recycling. You can sell new recycled products. There’s growth potential there. So it gets more attention, even though only a small percentage of what we “recycle” actually makes it back into the system.

But there are better models. Cradle-to-cradle design, for instance. If a company is responsible for its product after its useful life — if it has to take it back — you can bet they’ll design it to be repaired, reused, or easily disassembled.

And that’s what we’re missing: responsibility for the source of materials, and the destination of the byproducts.

Growing Up as a Species

Growth is wonderful — when you’re a child. If a four-year-old wasn’t growing, you’d worry. But if you or I started growing like a four-year-old, we’d panic. You’d be outgrowing your clothes, your house, your health.

At some point, growth becomes a problem. And biologically, our bodies know when to stop.

But civilisation? That’s going to take conscious effort.

And thankfully, movements like Degrowth are starting to explore what that might look like — not just economically, but culturally, spiritually, and socially. It’s not about going backwards. It’s about growing wiser, not just larger.

Measuring What Matters

One of the ways we could start making saner decisions — and temper some of the madness of endless growth — is by changing what we measure. Right now, we mostly just track economic activity. It doesn’t matter whether that activity is good, bad, or utterly destructive — if money is moving, it goes into the ledger as “progress.”

I’ve been lucky to be involved in a project that offered something better — something called Wellbeing Measurement, or more formally, the Genuine Progress Index (GPI). It’s a way of measuring not just economic growth, but also social and environmental indicators of wellbeing.

Let me give you an example.

If you heard a loud crash outside your window right now, and saw two cars all smashed up, what you’re witnessing — in the current system — is economic opportunity. There’ll be repair bills, medical expenses, maybe some legal fees, police involvement… and all of that adds to the GDP.

Our system doesn’t distinguish between regrettable expenditures like those, and positive ones — like education, healthcare, or making a beautiful table and chair. As long as money changes hands, it’s all treated the same.

The Genuine Progress Index changes that. It differentiates between helpful and harmful spending. It also includes social and environmental indicators — the kinds of things that really shape the quality of our lives.

The Genuine Progress Index differentiates between helpful and harmful spending.

It also includes social and environmental indicators — the kinds of things that really shape the quality of our lives.

I ended up working with an MP here in Canada who was interested in the idea after hearing about it from a Green Party candidate.

The Green Party fellow didn’t have much time as a full time dentist with four children. When the man that won the election said “Let’s do it", the Green guy suggested me.

So we got to work.

I became the go-between — drafting letters, fielding responses, coordinating with Parliament. It was amazing how quickly it could move: you’d send something out, and the next day you’d get it back translated into proper parliamentary French, with the full mail-out handled by the House of Commons.

Anytime I talked to a group about it, they had something they wanted to see reflected — environmental concerns, social inequities, crime rates, community health. It didn’t matter if they wore sandals or pinstripes. Everyone had something they cared about that wasn’t being captured by the GDP.

And for a moment, it looked like it might go somewhere.

We got a motion passed in the House of Commons — a clear majority vote — that said the government should develop a national set of wellbeing measures. But here’s the thing: the House of Commons isn’t the same thing as the government.

I learned that the hard way.

To be in “the government,” in our system, you have to be part of the cabinet — the prime minister, ministers, and parliamentary secretaries. The rest of Parliament? They can pass motions, but unless the government decides to act on them, nothing changes.

In this case, the government didn’t act.

What really worried them, I think, was that this index would go through Statistics Canada and be reported directly to the public — not filtered through a minister or buried in spin. That’s what made it powerful. And that’s what made it dangerous.

Because when people can see something — really see it, with credible data — they tend to want action. If the air is getting worse, if the water is drying up, if social cohesion is fraying — people notice, and they care.

A wellbeing index gives us a dashboard. Right now, we’re driving a bus using only the speedometer. Faster must be better, right? But it helps to look out the window. Check the fuel gauge. Glance in the rear-view mirror.

Otherwise, you don’t notice you’re heading off a cliff until it’s too late.

Bhutan, GPI Atlantic, and the Power of Possibility

A fellow named Ron Coleman helped us craft our motion. He runs GPI Atlantic, and he’s also spent a lot of time working in Bhutan, the small Himalayan country known for pioneering Gross National Happiness as an alternative to GDP.

There was even a big moment at the UN where Bhutan’s king, its prime minister, and people like Ron gathered to push for global uptake of these ideas. For a while, it felt like a tipping point.

But then the World Bank and the IMF came knocking.

They told Bhutan that if they pursued this — if they really tried to embed wellbeing into their economic metrics — the financial institutions would demand immediate repayment of their loans. It was a threat dressed as diplomacy. An offer they couldn’t refuse.

So the initiative fizzled. But not before a lot of people learned about it.

And the idea still lingers. It’s still powerful. Because at its heart, it’s about paying attention to the right things.

On Setbacks, Debt, and the Quiet Fight for What Matters

At this point in the session, someone asked me a very thoughtful question — about what it’s like to experience major efforts being thwarted. The kind of moments where you’ve done all the right things, built the coalition, passed the resolution… and then the rug gets pulled anyway.

They asked how I kept going. How I didn’t give up.

It’s a fair question.

I’ve seen it happen more than once. The Genuine Progress Index effort in Canada is one example — we got the motion through the House of Commons, but the government didn’t act. Same thing in Australia, I later found out. There was political will, until there was actual power — and then it vanished.

I remember another moment clearly. It was just after the fall of apartheid in South Africa. A representative from the new government came to a Canadian Environmental Network meeting and told us how excited they were about rebuilding the country. They had plans. Big ones. But almost immediately, the IMF arrived with a reminder: your first obligation is to repay your debts.

Before you take care of your people, you take care of the money.

That kind of logic runs deep. During the global recession in the 1980s, there was a huge push to cut spending — social services, education, even military budgets. But not once did anyone suggest cutting back on interest payments. That was untouchable.

“Before you take care of your people, you take care of the money.”

That kind of logic runs deep. Once, charging interest was a deadly sin. Now, it’s the one thing no one dares to question.

It wasn’t always like this.

In biblical times, usury — charging interest — was considered a deadly sin. In early economies, if you loaned money to a farmer and their crop failed, you shared the loss. Today? If your crop fails, the bank takes your land.

We’ve turned something that used to be taboo into something beyond question.

Writers like Michael Hudson have documented this shift beautifully. In ancient Greece and Rome, there were mechanisms to cancel debt when it became too burdensome. In fact, the golden age of Greece began when citizen debts were wiped out. People got their land back. And suddenly they were free — to build temples, to write philosophy, to invent democracy. Not because someone handed them luxury, but because they were no longer shackled to lenders.

That’s something to think about.

Even now, the logic of capital is eating the world. You hear, “We need lithium.” And the next thing you know, someone’s buying up land in Peru. The bottom line has become a kind of false religion — one that promises abundance for all, but delivers extraction and dispossession. It has no compassion. And it doesn’t know when to stop.

And yet, amidst all this, I don’t lose hope. Because wherever I go, I see something else stirring.

People are sharing resources in local communities. They’re joining Buy Nothing groups, trading time and talent and care without money. I met someone who said the only reason they still have Facebook is for their Buy Nothing group — it’s where the good-hearted people are. And that tracks with my experience.

And there’s more. A book called Blessed Unrest catalogued tens of thousands of citizen organisations doing good work, quietly, all over the world. It’s a movement that doesn’t always make headlines — but it’s massive. And it’s growing.

Someday — maybe not soon, maybe not all at once — we’ll win. Maybe not the day. But the future.

And if I can help move that needle — even a little — then I’ll keep at it.

Because I still believe in what’s possible when people are freed from debt and allowed to follow their passions. That’s the soil where culture grows.

Life Is a Gas (in More Ways Than One)

So now I want to talk about life — which, for me, is the exciting part. If you saw the little video we made recently, some of this might sound familiar. And if it does sound familiar, I encourage you to learn it and share it. It’s a story that has a way of sticking with people — and it reminds us that it really doesn’t take much to live well.

A short retro-style animated video written by Mike, bringing this part of the talk to life in a playful, digestible way.

Let me tell you about an experiment.

Back in the 1600s, a scientist named Jan Baptista van Helmont took a five-pound branch from a willow tree. He also took 200 pounds of soil — dried it completely in an oven so he could measure it precisely — and planted the branch in a large pot.

He watered it only with rainwater or distilled water. No fertiliser. No new soil. Just water and time.

Five years later, the branch had grown into a full bush. He removed it and weighed it again. The bush now weighed 169 pounds.

Then he dried the soil again and weighed that too. It had only lost two ounces.

Think about that. You’ve got a gain of 164 pounds in biomass… and only two ounces of soil were used up.

So where did the rest come from?

From the air. From water. From carbon and oxygen and hydrogen — gases floating freely in the atmosphere, all around us. Life, quite literally, is made of air and light and water.

And that’s when I like to say: Life is a gas. And I mean that in two ways.

First, in the literal, scientific sense — most of what makes up our physical bodies comes from gases in the atmosphere. These are not scarce resources. They’re abundant. We’re made mostly of stuff that floats invisibly around us. And that’s a hopeful thought.

Second, in the other sense of the word — life is a gas! It’s fun. It’s joyful. It’s meant to be lived, not hoarded or endured or traded away for efficiency.

And that brings me to something I’ve come to believe very deeply:

Joy Is the Most Radical Thing You Can Do

Right now, we’re facing some of the most serious challenges humanity has ever encountered. Climate change, inequality, ecological collapse — it’s heavy stuff.

But the most potent thing you can do in the face of all that… is to enjoy yourself.

Not in a consumerist, binge-on-Netflix-and-ignore-the-world kind of way. I’m talking about true enjoyment — the kind that comes from connection, creativity, and curiosity.

Spend time with people you love. Learn something new. Play music. Dance. Cook. Share a laugh. Help someone. Be helped.

Those things don’t just make life worth living — they’re actually more fulfilling than anything you can buy. You might get a little buzz from purchasing something shiny, but it fades. You make a friend, though — that can last a lifetime. You learn something — that reshapes how you see the world forever.

There’s so much richness to be found in the lived experience of being human. And if we embraced that, we wouldn’t need to produce and consume on the scale we currently do. We wouldn’t need to manufacture junk designed to break after one use.

We could live well — and leave room for others to do the same.

Of course, I’m not saying we can forget about the material. We’ve still got that two ounces of soil. That’s part of the picture too. But the rest? The rest is air. Possibility. Imagination. Love.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s enough.

Spaceship Earth and the Long Body

One of the most important ideas I ever came across came from Buckminster Fuller. You might know him — he died back in the ’80s, but he was a brilliant, big-picture thinker. A kind of cosmic engineer-poet. He had a way of pulling ideas down from the stars and handing them to you like pebbles.

He wrote a book called Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. And in it, he said something simple but profound: we need to treat Earth like a spaceship.

Think about it. A spaceship has limited provisions. There’s only so much fuel. Only so much room to throw your garbage. You’ve got to be smart about your systems, because there’s no outside to throw things into. No infinite anything. And if you design your life with that in mind, you can thrive.

We’ve got a good star, just the right distance away. Plenty of energy. But everything else? That’s finite. If we build our societies to work within those constraints, we can cruise through the cosmos for a very long time.

When I first read that — I was in my early twenties — it hit me like a bell. I dove deep into his work after that. I even got to see him speak once, at the University of Guelph. A few of us drove up from Toronto. It was three hours of pure idea-stream. Just concept after concept, like fireworks made of thought.

But the idea that stuck with me most was something he called Pattern Integrity.

He explained it with the image of a slipknot on a string. As the knot moves down the string, the material passes through it. What you’re seeing stays the same — the same knot — but none of the original material remains. All the molecules have changed. But the pattern endures.

That, he said, is the real you.

We’re all patterned integrities. The substance of our bodies changes constantly — most of it within a year. Within seven years, there’s practically no trace of the material you were originally made from. And yet, you’re still you.

You are not your matter. The cells of your body come and go, but the pattern remains.

That’s the real you — a patterned integrity.

We are spirit woven through the stuff of Earth.

If you take all the matter that enters your body from conception to death — all the air, food, water, minerals — that’s your long body. And at any one moment, only a tiny portion of it is inside your skin. The rest is out there — in the trees, in the soil, in other people, in the air.

And the long bodies of every human, every animal, every plant — they all draw from the same shared biomass. We’re not separate. We’re cycling through one another constantly.

So one of the things we have to learn, as a maturing species, is this:

We need to get toilet trained.

Because it is completely unacceptable to take substances that are toxic to life and dump them back into the biomass — the very stuff that all life draws from to make itself.

Closing the Loop

That’s one of the things we’re working on with our EcoVillage project — closing the loop. We call it joining the ends of the rope.

We’ve built what we call a com-pooster — a system that breaks down human waste, kitchen scraps, and garden leftovers. It heats up enough to kill off any pathogens, then it sits for several years. And after that, the nutrients return to the soil.

The soil feeds the plants. The plants feed us — or animals, which feed us. The only thing lost in that cycle is energy, which radiates out from our bodies as we live and metabolise. But the sun shines down and gives it back.

That cycle — sun, soil, plant, person — can go on for as long as the sun shines.

Compare that to conventional agriculture. We mine phosphorus and potassium from rocks in faraway places. We produce nitrogen using natural gas — energy-intensive, transport-intensive, resource-limited. That system can’t last forever.

But any community that forms a living relationship with its own soil? That community can last a very long time.

If you know what keeps you alive — and if you can grow good food in healthy soil — then you’ve got health. And if you’ve got health and aliveness, well… then you’ve got joy. You’ve got music, stories, shared meals, moments of beauty. That’s a life.

And that’s a much better way to run a civilisation than just trying to see who can die with the most toys.

Human Beings: Strange, Capable, and Full of Potential

You know, human beings are really quite extraordinary creatures.

We’ve got thumbs — which might sound basic, but it’s a big deal in the evolutionary toolkit. Sure, there’s creativity in the animal kingdom — crows, octopuses, and all the rest — but nothing quite like what humans can do.

We have good senses, too. Not eagle-level — they can spot a mouse in the grass from a mile in the air — but we make up for that with tools. Telescopes to see the edge of the universe. Microscopes to peer into atoms. And we don’t just observe — we make sense of what we see. We ask, How does this work? and How can we work with it?

And perhaps most amazing of all: if someone spends a lifetime studying a piece of the world — really grokking it — they can share that understanding with the whole planet, instantly. We don’t need to wait generations for knowledge to spread. We’ve built a species-level nervous system.

We are, by all accounts, a species capable of managing a planet — an abundant one, at that. All we have to do is make that our purpose.

Of course, there are still entrenched interests — people deeply addicted to wealth and power. But those systems are starting to wobble. And at the same time, alternatives are blossoming. All over the world, in quiet corners and loud pockets, something new is growing.

And that brings me to a metaphor I love.

As entrenched interests begin to wobble, alternatives are already blossoming. In quiet corners and loud pockets, something new is taking root.

Becoming Butterfly

You’ve probably heard the story of how a caterpillar becomes a butterfly. I think about it often.

The caterpillar’s life is all about consumption. It eats and eats, collecting natural resources, expanding, growing. Sound familiar?

That’s where we are now, as a civilisation — deep in the caterpillar phase.

But then… something changes. The caterpillar senses enough. And that’s an idea we struggle with in our society — the idea that we might have enough. But the caterpillar gets it. It forms a cocoon. It stops. And it transforms.

When it emerges, it lives lightly. It sips nectar. It’s beautiful — a symbol of joy, grace, and delicate presence. And its entire purpose becomes ensuring the well-being of the next generation.

I’ve told this story many times — especially when my book came out. And on tour, I kept meeting biology students who added new layers to it.

One told me that when the first butterfly cells begin forming inside the caterpillar, the caterpillar’s immune system sees them as threats — and tries to kill them. They’re called imaginal cells, and they represent the new. The possible. But the old system resists.

And if you’ve ever tried to live differently — to slow down, change careers, care more, buy less — you’ve probably felt that. Society says: Just get a job. Spend more. You’ll feel better. It’s hard to go against the grain alone.

But another student told me what happens next: as more imaginal cells appear, they start to band together. And once that happens, the immune system can’t stop them. A new pattern forms — collaborative, resilient, alive.

Eventually, as enough of the caterpillar has become butterfly, something amazing happens: the rest of the caterpillar’s body liquefies — and flows into the form of the butterfly.

It’s not a gradual shift. It’s a threshold event. Once there’s enough alignment, the transformation accelerates. The structure of the old becomes the substance of the new.

That’s what I think we’re living through now. The imaginal cells are gathering. They’re sharing knowledge, building community, strengthening the pattern. And when the time comes, the transformation could be swift.

As a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, its old body liquefies and flows into a new form. That’s what I think we’re living through now.

Last summer, we had a few monarch butterfly eggs in our house. We watched them grow into caterpillars, hang into a J shape, form chrysalises, and — one day — open into butterflies.

It’s still magic to me.

Why We Need Each Other

As we move into this new way of living, one thing becomes very clear: we need each other.

One of the most powerful forces in society is legitimacy — the need to belong. We want to be good. We want to be seen as part of the group. And that drives more of our behaviour than we like to admit.

Try this thought experiment: take a backpack full of tools and walk into the wilderness with the goal of surviving for two years. What are the odds you’d make it out healthy?

Some people might say it sounds fun — and maybe, in private, they’d enjoy the challenge. But almost no one could actually do it. I know I couldn’t.

And even if you did, you’d be using tools someone else made. Techniques someone else taught. Even the language and thoughts in your head came from other people.

A human being without society is like a computer without an operating system. All the hardware is there, but it can’t run.

So we conform — at least to some extent. We adopt the values of the society around us, because it’s the price of admission. And right now, the dominant value is still: earn and spend as much as possible.

But that’s changing.

More and more people are saying: That’s not it. That’s not the way. A good human now is someone who lives lightly, loves deeply, and manages the material world in a way that serves the next generation.

That’s the butterfly way. It begins in hunger, in growth, in accumulation. But it ends in beauty, in lightness, and in care.

And that, I think, is a civilisation worth becoming.

A good human now is someone who lives lightly, loves deeply, and manages the material world in a way that serves the next generation.

🧭 Further Exploration

At Grokkist, we believe that wisdom shouldn’t just stay inside the room — or the Zoom. We curate what emerges so others can build on it.

Below you’ll find a collection of resources mentioned during the session or contributed by attendees. Some are Mike’s own work, others were sparked in the discussion. Together, they offer paths for deeper exploration, connection, and action.

This is one of the ways we live our ethos: not just enjoying meaningful conversations, but turning them outward into living, shareable wisdom.

Mike’s Resources

Mike has spent decades making practical wisdom accessible. Many of these come from his SustainWellbeing site.

- 🗺 Guideposts for a Sustainable Future

- 🔁 Three Potent Steps for a Sane Economy

- 💗 Learning, Love and Laughter: A Key to Sustainability

- ⛵ Getting From Here to There

- 📦 More Materials…

- Contact Mike: [email protected]

🎬 Watch: To Be Alive and Well

If you enjoyed the talk — or if you’d like a lighter, animated take on the key ideas — this short video brings it all together with a smile and a wink.

Written by Mike, it’s a retro-style info reel that shows how sustainability, joy, and societal transformation might just go hand in hand.

🌐 Mentioned in the Session

These were referenced by Mike or shared by participants in the live chat. We’ve gathered and grouped them here for you to explore further.

🌍 Alternative Economies and Measures

- Genuine Progress Index Atlantic

- Wörgl and Stamp Script Currency

- Process of Money Creation (Wikipedia)

- A Mindful Growth Ideology – Lalith Ananda Gunaratne

- Charles Eisenstein – The Ascent of Humanity (Ch.4 on Money and Poverty)

🔧 Tools for Local Exchange

🤝 Cooperatives and Solidarity Economy

🌿 More Curiosities

💬 Want to Add Something?

We’d love to keep curating this together. Share it with us by leaving a comment below, or post in the Grokkist Network if you’re a member.

This is how we do it at Grokkist — by living the conversation forward.

Member discussion