We are raised in a culture of radical individualism and you-do-you self-fulfillment. We are told we can do anything, become anyone.

The same applies to our philosophies: if we dig deep enough—questioning our ethico-onto-epistemological assumptions—we can supposedly create our own. There is even a book on creating your own religion.

This mindset is deeply rooted in mechanistic thinking that reduces the world—and ourselves—to projects to be engineered. Tara Isabella Burton, in her book Self-Made, argues that our belief in self-making stems from a “radical, modern reimagining of the nature of reality”—one that replaces a God-ordered universe, where roles were fixed by birth, with a worldview where the self is both creator and creation.

Burton writes:

“The idea that we are self-makers is encoded into almost every aspect of Western contemporary life.”

“We not only can but should customize and curate every facet of our lives to reflect our inner truth… We are all in thrall to the seductive myth that we are supposed to become our best selves.”

Yet when we try to find a philosophy - at least in the way I talk about it -we aren’t just attempting to create our best self. We’re also attempting to create—and enact—a better world.

Self-made is failing us

We have tested this self-made approach for long enough to realize that either the assumptions of self-making are wrong, or most of us are incapable and inherently flawed human beings. This is because, for many people, it feels like we don’t have full control over who we are becoming, despite all the possibilities available to us.

Self-help literature thrives on the assumption that we can do everything ourselves, yet we never seem to be quite able to achieve that.

The result is often self-blame, shame, and, in severe cases, hopelessness and depression.

As I recently shared, the approach of trying to use the tools that worked for others (e.g., the authors of self-help books) is deeply flawed. While we can learn from these books, the tools need to become part of us. We must immerse ourselves in them—like tofu soaking up marinade—until the flavor becomes part of who we are, aligned with our ways of knowing, being, and acting in the world. Only then can they shape who we are and have a meaningful impact on us.

As more of us question the “you-do-you” promise—that we can become anyone if we just try hard enough—we tend to respond in one of three ways:

- Doubling down on self-mastery, insisting that any inability to transform lies solely in our own shortcomings.

- Blaming systemic barriers, arguing that our environment—laden with oppressive systems and structural inequities—is the dominant force affecting our flourishing.

- Turning inward toward therapeutic healing: the idea that if only we could repair the damaged parts of ourselves (whether from trauma, developmental imbalances, or other deficiencies), personal growth would finally be possible.

As more of us question the ‘you-do-you’ promise, we tend to respond in one of three ways: mastery, blame, or therapy.

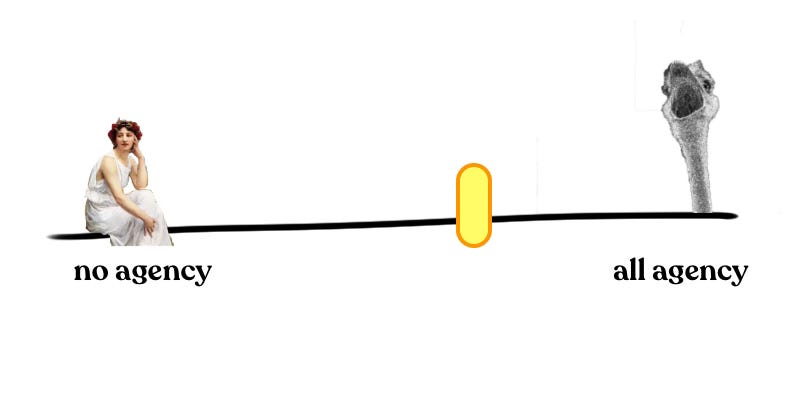

But at the heart of all these responses lies the same puzzle: where does our agency really live? Is it something that resides entirely within us, something that emanates only from outside, or something that exists in the relation between the two? Do we have no agency, complete agency or everything in between?

A matter of agency

Agency is our ability to:

(a) make choices, and

(b) to act on them.

One of the core challenges of our time is that even if we do make choices, such as wanting to live a regenerative lifestyle, we are often unable to act upon that choice. The (b) in agency has thus become difficult.

But that’s another story and today, let’s focus on (a): the choice.

A relational approach to agency tries to reconcile the differences by refusing the binary of “self vs. system” altogether.

Through a relational lens, the self is neither sovereign nor passive, but a relational process—a dynamic entanglement of biology, culture, ancestors, ecosystems, and choices. We are not self-made, but world-made.

We are not self-made, but world-made.

Our becoming is co-authored by the air we breathe, the stories we inherit, the microbes in our gut, and the economic systems that shape our opportunities. To “become anyone” is not an act of willpower, but an act of intra-acting reciprocity.

For example, a seed holds potential, but its growth depends on soil, rain, and sunlight—all of these are beyond its control. Similarly, our agency flourishes only when nested within relationships of care: to land, community, and the more-than-human world.

From a relational perspective, our task is not to fix ourselves in isolation or strive to become anyone at all costs. Instead, it’s to let go of the self-made ideal and turn our attention to the conditions that allow life—our own and others’—to thrive.

Our self-making, in this view, is never a solo act, but a shared, ongoing collaboration with the people, places, and patterns that shape us.

Agency in our philosophies

If our “self-making” is always a collaboration, then crafting a personal philosophy cannot be a solitary act of willpower.

As I have recently written:

"Philosophies are actual occasions - with their own agency. Your philosophy isn’t a puppet you control, it’s a presence you collaborate with. It evolves as you meet new people, read new books, or walk through a forest and feel your separateness dissolve…..

A living philosophy isn’t a monologue—it’s a polyphonic conversation. It listens as much as it speaks. It’s accountable to the communities (human and otherwise) it impacts.

To have a philosophy, then, is to host a lichen: part you, part other, wholly intra-dependent.

This shifts philosophy from a noun to a gerund: not truth but truthing, not being but becoming.

This doesn’t mean surrendering agency. It means recognizing that agency is always shared. Just as a gardener collaborates with sunlight, soil, and seasons, we collaborate with the philosophies that root us. Sometimes they surprise us. Sometimes they wound us. Sometimes they compost into something new. But they are never passive."

(No)/all agency

I love thinking through a relational lens, but as someone who grew up deeply embedded in the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) world’s thinking, being, and acting, I often find it challenging to translate this into everyday life.

As a "fun" side story: while my Ph.D. focused on a relational approach, it was only after publishing several papers and nearing the end of my writing that I realized I had written about relational approaches without grounding myself and my research approach in a relational way.

I think this is what Burton means by modern self-making: we perform the appearance of transformation without embodying its substance. We speak the language of change—because that’s easy—but often forget to live it, which is far messier, slower, and harder to sustain.

We speak the language of change—because that’s easy—but often forget to live it, which is far messier, slower, and harder to sustain.

And I understand why; it's messy and requires time and effort.

So, how can we embody the space between having no agency and full agency?

- Hold agency lightly. Even without hard data, it seems clear: people who act as if they have agency tend to be more fulfilled. While we acknowledge that agency is never complete, choosing to act anyway opens space for growth.

- Use what you’ve got. Our agency may be partial, but it’s real. Recognizing it is part of life becoming aware of itself. (Check out Paul Musso’s Microphilosopher for inspiration.)

- Treat your philosophy as an experiment. Not every belief needs to be an unshakable truth. Let your philosophy be provisional—something you test in the messiness of everyday life. It’s through living, reflecting, and even being wrong in public that your ideas become something you can live with.

- Stay attuned to feedback. Let your ideas evolve through interaction—with people, place, and the more-than-human world. Let it surprise you.

- Find your mirrors. We need others to discern which values are truly ours and which were smuggled in under cultural pressure. Authenticity isn’t invented in isolation.

- This is the work of being human. The process of “finding your philosophy” is actually the act of living philosophically. It’s slow, relational, and deeply humane.

- Slow down. You can’t build a philosophy between dinner and dessert. The effort required is also what makes it matter.

As Michael Easter says in his book The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort To Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self:

“Comforts and conveniences are great. But they haven’t always moved the ball downfield in our most important metric: happy, healthful years. Perhaps existing only in our increasingly overly comfortable, overbuilt environment and always obeying our comfort drives has had unintended consequences and caused us to miss profound human experiences.”

The myth of radical individualism promised mastery but delivered fragility.

The myth of radical individualism promised mastery but delivered fragility.

To forge philosophies that can regenerate us, we need to leave behind the fiction of the self-made self.

Agency is a matter of integrating diversity: human and nonhuman, past and present.

This doesn’t mean surrendering to fate.

May we tend to the relationships, ideas, and ecosystems that let our agency rot, root and bloom. It’s messy. Slow. But it’s the effort itself that seeds meaning.

Philosophy isn’t just a manifesto we write—it’s a composting, weathering, evolving life we live, one imperfect, entangled choice at a time.

Jessica explores the art of practical philosophy, helping others develop their own philosophy to navigate the challenges of the Anthropocene. Her work is a blend of interdisciplinary insights—from ecology and sustainability to spirituality and psychology—crafted into wisdom you can apply to daily life.

For more thought-provoking reflections on living a good life in a complex, changing world, visit Rewilding Philosophy to discover how to live in right relation, embrace paradoxes, and thrive in the gooey soup of meaning-making.

Member discussion