Shortly after, Alan began his Euro Book Trek to promote Salt & Seeds while exploring the myriad adaptations already taking root across Europe. This article is adapted from posts on his Substack, chronicling the adventure.

Leg 6: Venice – Books, Dogs and High Water

Venice has always been a place that seems both real and dreamt, an ancient city of salt-stained stone, stillness, and slow unravelings. After days of travelling through Europe, we arrived and checked into Hotel Have Venice, tucked away in Mestre. It’s cheap, a little rough on the outside, but fine inside, a base with secure parking, walking distance to the station, and one short train ride from the historic centre of Venice.

We arrived under an overcast sky, but it was still hot. Our two days were spent mostly wandering, not chasing sights but letting them happen. Venice rewards you for doing nothing in particular. Blink and you’ve entered a passageway like a dream sequence. One wrong turn and suddenly there’s a man in a stripy shirt smiling beside a gondola, or cross a little bridge to find a square filled with tanned thirty-somethings in designer linens, nursing Aperol spritzes, or someone hanging their pants out on a washing line.

One alley led us to a little wall-mounted house-shaped box that read: La Casa Del Libro – Prendi o Lascia un Libro (The Book House – Take or Leave a Book).

I left a signed copy of Salt & Seeds tucked inside, as another donation on this long Book Trek around Europe. These moments felt like offerings more than drops; little ways of saying, "I was here, and had something to give, so come and find it."

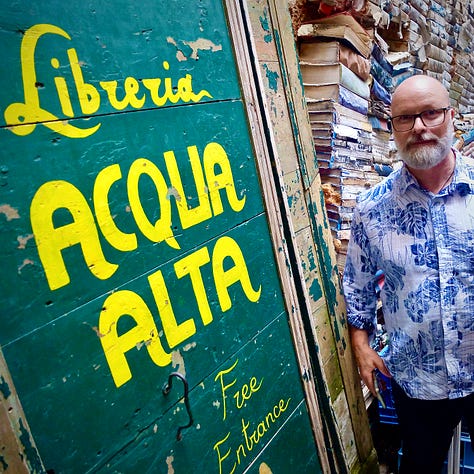

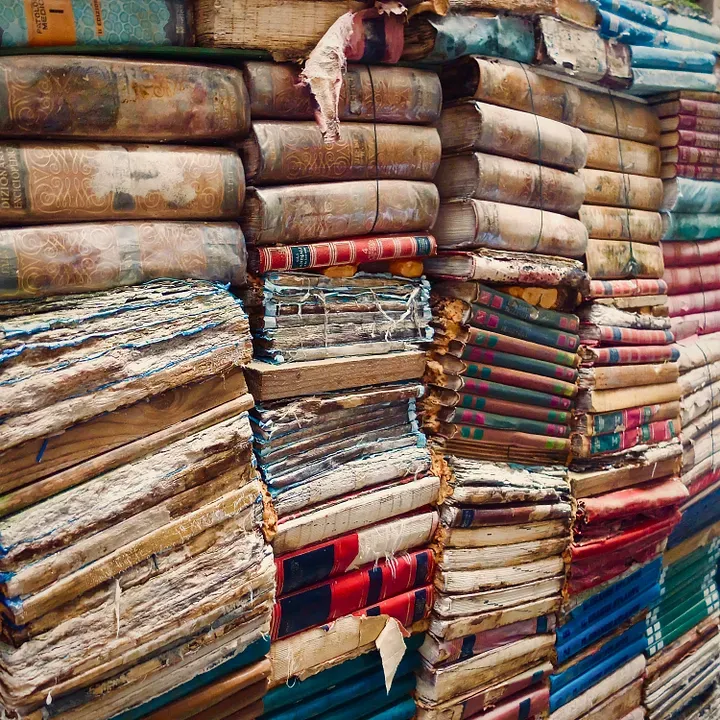

Our literary pilgrimage took us next to the Libreria Acqua Alta, a name that translates to "High Water Bookshop." It’s famous for good reason, inside are teetering stacks of books stored in bathtubs, gondolas, and rowing boats to protect them from Venice’s seasonal floods. They even have another gondola outside the back door that opens onto a canal. It’s the official fire escape, they say, with a sign to prove it.

Founded by Luigi Frizzo in the early 2000s, Acqua Alta has become one of the most photographed and beloved bookstores in the world. What began as a quirky idea to safeguard books from the acqua alta — Venice’s increasingly frequent flooding — has grown into a symbol of creative resistance. The shop doesn’t just store books; it absorbs the water, the tourists, the cats, and the slow crumble of the city, with humour and defiance.

Every part of Acqua Alta tells a story of resilience. The stairway made of water-damaged encyclopaedias in the courtyard; the books climbing walls on shelves made from old kayaks; the gondola at the centre filled with books instead of passengers — all are visual poems about adapting rather than retreating. It’s no museum. It’s lived-in, chaotic, and stubborn in the best of ways.

The cat with the watchful eyes kept the till area warm. I left a signed, waterproofed copy of Salt & Seeds with the staff. They seemed pleased to meet me and we chatted briefly before the many customers demanded their attention. Perhaps they’ve seen many books come and go, but the subject matter of Salt & Seeds earned my book the extra attention. Maybe it’ll float for a while, and find a reader who understands what it’s like to cling to something precious in rising tides.

I must admit that having a book in Acqua Alta has been a dream since I wrote Salt & Seeds, and one of the main destinations for this book trek.

Next, it was time to taste the vegan gelato; it was cool, smooth, and very welcome in the heat, but lacked the sweetness of traditional gelato. The seller must think that if you don’t want cream, you won’t like sugar either. I hope they continue to expand the vegan options beyond one flavour and find a demand for it among tourists.

I took a few shots of whatever caught my eye: a discarded Aperol Spritz cap on the edge of a canal, like a still life in orange and stone. Souvenir shops displayed a carnival of grotesque and beautiful masks, some theatrical, some mechanical. There were bobbleheads of Rocky, The Rock, and Ronaldo. All of it surreal and silly and exactly what it should be.

Perhaps my favourite images, though, were of the dogs. Patient, proud, unhurried. One peed up a shopfront without apology, just as I went to photograph it. Another stood in the middle of a busy square, more composed than any of the tourists, not appearing to have anyone to hold the lead. Boys kicked balls around, but this fluffy local just locked eyes with me across the square and stayed very still for a portrait.

In Salt & Seeds, I wrote about a world slowly learning to float rather than fight the rising sea. Venice felt like a real-world cousin to that imagined world, beautiful and cracked, resilient and ridiculous. It’s not pretending it won’t flood. It adapts. It weaves boats into its architecture. It stores words in watertight barrels. It survives with absurdity and grace. I didn’t visit Venice for the big icons.

I came to walk, notice, and leave books behind. Mission accomplished.

Leg 7: Austria – The Hills Are Alive

Driving from Italy into Austria felt like turning a page into another chapter of snow-capped altitude and forest stillness. The road ducked through tunnels and wound through alpine passes that grew quieter and greener with every mile. The heat and passion of the Mediterranean world faded behind us. As we climbed, the temperature dropped, and the villages seemed to grow more inward-looking, their ornate red-wood shuttered chalets, clutching the slopes like secrets.

We eventually reached our next base at the Pass Lueg Hotel, perched high against the mountain greenery, with the main road diving into a tunnel beneath it. The view from our pine-clad room was stunning, a full sweep of mountain, forest, and sky, framed by the deep overhanging eaves of classic Austrian chalet design. The building itself could tell some tales. Paintings of generations lined the walls, and a monument to fallen soldiers stood quietly at the gate, as a testament to the region’s turbulent past.

After a short rest following the long drive, we headed into the closest settlement: Golling an der Salzach, a tidy town that felt like it had one foot in a postcard and one in a working life. We ate among the locals, choosing the cheaper of two pizza restaurants that strangely sat opposite each other in the centre. We picked the one that was most populated, as the locals may know something we didn’t.

We soon discovered that this one had something the other definitely lacked for local appeal — a dartboard. A darts match was soon underway right next to our table, but fortunately, everyone had a good aim. It was the kind of place where your presence is acknowledged but never fussed over. Just how we like it. And the local draft beer was good.

The next morning, we were up early and in the car, heading into Salzburg for the day. An attractive city famed as the birthplace of Mozart and the set for The Sound of Music. Pictures of Julie Andrews adorned gift shop windows and bus tour stops. A huge makers' market lined the riverbank, with crafters of every kind. Locals in lederhosen and traditional dresses served in shops filled with cuckoo clocks and music boxes.

I made a beeline for the Buchhandlung Hollrigl bookshop, historic stalwart of Austrian literary history, and the oldest in the country, empowering readers since 1594. It’s a large shop, one of the biggest we visited on the entire trip, with an inspired selection of English-language novels. What an honour to add to that collection of legendary stories with a signed copy of my own book.

Across the square from the shop stood two telephone boxes. Remembering the book-filled phone box I’d found earlier in the journey, I had to peek inside. Sadly, no books here. I may or may not have fixed that. You’ll have to go and see for yourself.

Salzburg offered many museums — dedicated to Mozart, Austrian history, and even Christmas, with a particular emphasis on Krampus. The cathedral was stark compared to the golden trappings of Venice’s Christian shrines and the mosaic ceilings of Lourdes, but it had everything it needed: an ornate altar and a contrastingly functional confessional, marked by hand-drawn signs.

The litter bins on Salzburg’s streets had solar-charging lids, and the telegraph poles were wrapped in thick green foliage, signs of a city striving for a greener future.

The famous Mirabell Gardens were impressive, framed by the castle backdrop and full of familiar scenes from the musical that brought them to global attention.

Yet not all was idyllic. There was an undertone of right-wing propaganda, and thankfully, some stickers from the opposition, to keep things in balance. A large group of Ultras marched intimidatingly through the tourists on the bridge, who were admiring the exhibition of Jewish WWII survivors. The Ultras set off flares and pasted their colours on the lamp posts. A reminder that echoes of history’s most shadowy episodes are often glimpsed in the actions of today’s generation.

Thankfully, Salzburg also had a fine selection of friendly four-legged residents to photograph. Here are some of my favourites:

That night, back in the mountains, thunder rolled in. We lay in bed with the windows wide open beneath those wide wooden eaves, and not a drop of rain touched us. Just the cool breath of the storm, the scent of the trees, and the soothing patter of rain between deep, rumbling claps of nature’s power. There was something ancient and grounding about listening to mountain thunder echo through the gorge, a lullaby played by water on stone.

In the morning, we followed the Gollinger Wasserfall gorge trail, which conveniently began just metres from our front door. The path tracked the rushing stream between cliff walls, draped in moss and ferns. Water roared through deep holes in stone, carved over centuries. Never underestimate the power of water to change a landscape. It carves and sculpts, even granite caves before it.

The whole region felt like a resting heartbeat between the busier stretches of this marathon book-trek. A moment to breathe in the Alps. A pause between pages.

But the forest beauty of this mountainous land masks a terrible chapter in Europe’s history. Just a few miles through the pass lies the Dokumentationszentrum Obersalzberg, a museum built on the site that once housed Adolf Hitler and his closest strategists, a place from which mass murder was planned, and miles of tunnels dug by forced labour, to protect the riches of the guilty.

We walked its halls and subterranean passages, confronting the depths of cruelty that humans can inflict on one another, when ideology is weaponised by charisma and power. There would be more to uncover about that harrowing legacy when we reached Berlin. But for now, we turned eastward once more, crossing into the Czech Republic.

Leg 8: Prague, Czech Republic – A Birthday, a Beaver, and a Golem in the Shadows

We arrived in Prague in the early hours of June 8th, after one of the most harrowing drives of the entire trip. Having been delayed by Harrison’s earlier medical issues, we pushed through to the Czech Republic at night and on to Prague. It proved to be a long, tense journey through poorly lit motorways. We were overtaken constantly by lorries and vans doing terrifying speeds, many with only one headlight, and none at all on the back. One particularly ominous, battered old van had just one flickering front light, and it was tailgating us no matter how fast I went, like Jeepers Creepers. I guess they were using my lights as their guide, in the absence of their own.

By the time we reached Prague’s city streets, lit mercifully by amber street lamps, I felt the tension drain from my body. We parked up and checked into Hotel Otakar, with a friendly, tall, blonde guy at reception. He spoke English better than me and had noticeably large hands. We carried the bags up an endless staircase and collapsed into the apartment, letting the distant hum of traffic and the scent of spalling stone walls lull us to sleep.

The next morning was Harrison’s 21st birthday. I woke early and hung a sparkly Happy Birthday banner between the radiators. Sara had been hiding it along with his birthday presents since we left England. The city looked and felt completely different by daylight, framed through the skylight windows, Gothic, ornate, storied, alive. After a session of watching Harrison rip the wrapping off his gifts, we headed into town. The tram stop was right outside, and the trams were excellent — regular, cheap, and reliable. Prague’s transport system, even with its quirks (more on that later), puts many larger cities to shame, including my own.

I was approached by a cheerful older man on the tram, wearing jeans he had sliced open from thigh to ankle for ventilation in the heat. He spoke very little English, and I spoke virtually no Czech, but we understood each other. He liked my beard, and I respected his too. He was fascinated that I was an Englishman with an old Russian camera, and he told me he was very fond of King Charles. He was under the impression that our monarch is extraordinarily tall, which isn’t strictly accurate, but I told him I’d have to take his word for it, as I’ve never met the King in person. Before getting off, he asked me to take a quick photo of him. I was happy to oblige. He left with a wave and the same wide grin he’d arrived with.

When we reached the centre, we began with a directionless wander, stopping to marvel at the buildings that seemed stitched together from centuries of stories. We found the iconic Charles Bridge, lined with life-sized statues of saints, each burnished by wind, rain, and reverence. Below us, the Vltava River moved slowly, the colour of old pewter. It was good to see a working water wheel; it’s a technology we should revisit.

We walked up through winding streets to the castle grounds, where the castle itself was sadly closed, but the view over the gothic cityscape was worth every step. Up there, nestled behind ivy-covered walls, we found a beer garden, and we lingered, examining the spires and steep rooftops of the old city, rolled out before us like a carved wooden toy village.

Eventually, hunger got the better of us, and we made our way back down. Back in the centre, we passed a photo exhibition by Tomki Nemec displayed in the windows of a concrete office-style building, black-and-white images of protests, banners reading NE NÁSILÍ (“No to Violence”), mixed with CND signs. A silent echo of the resistance movements that once filled these streets.

Finally, we made our way to Kmotra Kavárna, Prague’s oldest pizzeria, tucked beneath a bar in a vaulted cellar, adorned with an eclectic array of vintage lampshades. It felt like something from a Cold War thriller, a place where spies might have shared secrets over salami. Harrison, true to form, ordered a massive pepperoni pizza. We raised a quiet toast to his resilience and good humour through years of illness. He’d made it to 21, and that alone was reason enough to celebrate.

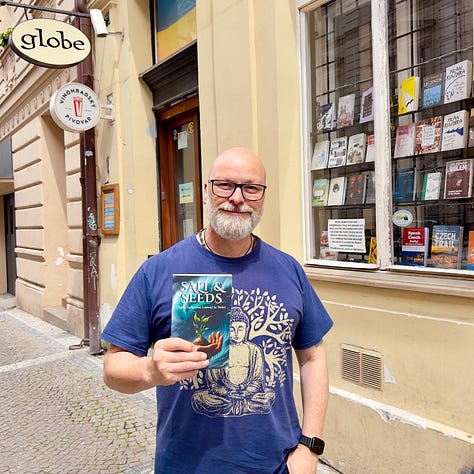

This leg of the Book Trek was rich with literary encounters. I visited The Globe Bookshop and met its American owner, Michael. We had exchanged emails in advance, so he was keen to receive two signed copies of Salt & Seeds — one for himself and one for the shelves. We spoke for an hour about publishing, sustainability, geopolitics, and the literary scene in Central Europe. Michael invited me to the Globe’s own Writers’ Group that evening, and I was honoured to join.

The event was warm, welcoming, and stimulating. The small, mezzanine meeting space, above the café, was cosily packed with booklovers. Two books were up for discussion: The Remains of the Body by Saikat Majumdar and A Demonology of Desires by Joe Grimm Feinberg. Both authors were present, generous in spirit, and compelling to hear. The conversation flowed as easily as the homemade iced tea. I told them about the wonderful, weekly writers group I attend at home called Writers@, and the monthly Grokkist Writing Salon that I facilitate online. I left bookmarks for future readers in the café and shop, and took away fresh ideas, inspiration, and community.

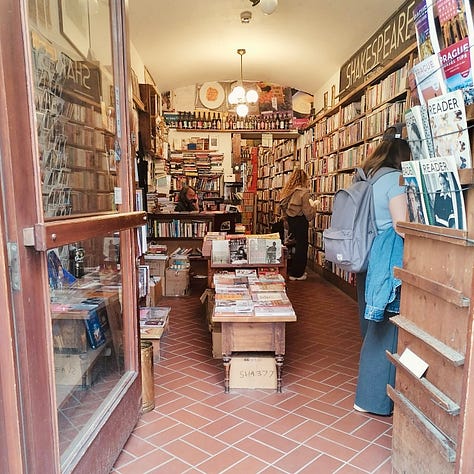

In the morning, I also visited Shakespeare & Synové, a quieter but equally atmospheric bookshop hidden down a cobbled lane. It looked small from outside, but magically opened out like a Tardis inside. I left a signed copy of Salt & Seeds there as well, in the hope that it might find its way into the hands of a curious local or thoughtful traveller.

One of the stranger moments of the trip came at the Franz Kafka Museum, where we were greeted in the courtyard by a copper-toned automaton of two men urinating into a shallow pool — absurd, irreverent, and entirely on-brand for the city's most famous literary son. The museum itself is a deep dive into paranoia, bureaucracy, and existential dread, fitting for a city once at the heart of multiple collapsing empires. There are echoes of Kafka all over Prague, T-shirts, souvenirs and very large statues.

Later, we wandered through the old Jewish Quarter, where I finally found something I’d long wanted: a small clay golem. I’m not Jewish, but the Golem legend has fascinated me for decades. The compelling tale of a rabbi who created a powerful protector to defend his people, only to lose control of the beast through neglect. A cautionary tale wrapped in mysticism, clay, and moral ambiguity.

Holding the golem in my hand, I thought of Prague’s own story: protective, dangerous, layered with complexity. It also reminded me of Uncle Ben’s warning to Peter Parker — “With great power comes great responsibility.” Something world leaders would do well to remember as they play with modern golems made of steel and code.

We made a point of visiting the famous astronomical clock, a mechanical marvel that has chimed since the 15th century. On the hour, a tiny skeletal figure rings a bell while the apostles parade by. It was every bit as eerie and delightful as I’d hoped, like watching a miniature ghost play peekaboo with time. The square and surrounding buildings were spectacular, a perfect place for gothic fantasy writers and vampire movie makers to find inspiration.

We carried on wandering through the surrounding streets, hoping to see something for Harrison to spend his birthday money on, and then there it was, Harrison’s perfect gift, a set of Russian dolls, painted as our local English football team, Hull City. Then just before leaving, we stumbled on a military surplus store down a quiet side street. Inside, we found treasures: a 1990s German combat jacket, a British helmet, and a Czech camo jacket. Harrison was thrilled. The lot cost me less than his birthday pizza.

And then, because Prague has a way of surprising you, we met a wild beaver under Charles Bridge. He swam up alongside the ducks who were begging for food, mimicking their behaviour, even waddling onto the bank to investigate us properly. He was offered a few leaves, which he took delicately, as if royalty. A wild beaver, face to face, in the shadow of Gothic towers and statues. I never saw that coming.

Leaving Prague for Berlin was almost as stressful as arriving. Following the Sat Nav out of the city, we were directed onto streets shared with trams. At one point, we were boxed in — tram ahead, tram behind — crawling through the city like impostors on a rail line. It felt surreal and embarrassing, as though we were moving in slow motion through a system designed for someone else. Eventually, we broke free, found the open road, and began the long drive north.

I’ll be back. We all will. Prague, with its gothic spires, riverside ghosts, warm-hearted bookshops, and surreal little miracles, left a mark I don’t want to erase. Here’s a few extra shots I snapped along the way.

Euro Book Trek 9th Leg: Berlin – Arts, Rats, and Disarming Attackers

Berlin was a city I had been looking forward to for a very long time. In my mind, it was the kind of place that would mix history, art, grit, and energy in a way few cities could. As it happened, it would give me all of that—and more than I bargained for.

I have just picked up the final developed rolls of 35 mm and 120 film from the trek. This episode will have more photographs than usual. Berlin, in all its contrasts, seems to demand it.

We drove directly from Prague, still carrying the echoes of that city’s Gothic charm, and checked into the Industrial Platz Hostel. Down by the reception was a bookcase saying ‘Book Exchange’, I left a signed copy of Salt & Seeds and a handful of bookmarks. That’s my small way of letting the book find its next home with a fellow traveller.

That first evening, we headed out to explore the streets around the hostel. They were lined with late-night kebab cafes and späti convenience stores, the air thick with the smell of sizzling meat. Vegan options were easy to find, which was a relief, but so, it turned out, were the rats and mice. They darted about under the table as we ate. Once you got used to them, they were almost cute in a Berlin sort of way.

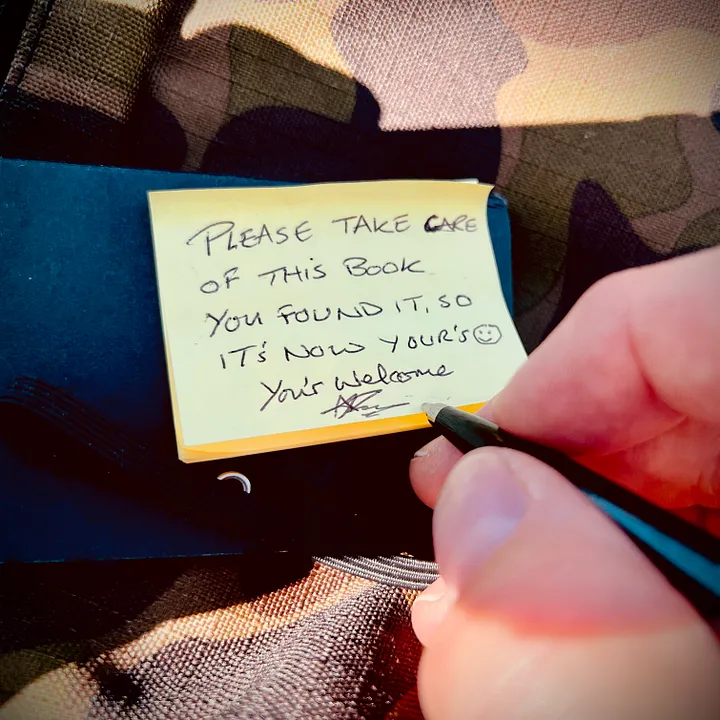

The next morning, I was up early with my camera and cassette recorder, capturing the sight and sound of the city waking. Then I walked to the East Side Gallery. I sat on a bench, reading Salt & Seeds until the walkway was empty, then signed the copy and left a note on it:

“Please take care of this book. You found it, so it’s yours. You’re welcome. Alan Raw”

I walked away and stopped to admire the artwork on the Wall. When I came back along the same stretch, a woman was sitting in my spot, already deep into the pages. I didn’t interrupt, just walked on, contented.

I met up with my wife Sara, and son Harrison, for some straightforward sightseeing. We toured the Topography of Terror museum, stood under the Brandenburg Gate, paused for a pint of Guinness in a Berlin Irish bar, admired the boxy charm of Trabants, tried on old military hats, and passed through Checkpoint Charlie.

Our last stop was the Reichstag. We were there to see a special projection celebrating the 30th anniversary of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Reichstag. Back in 1995, the artists had encased the entire building in shimmering silver fabric; now, an animation projected onto the façade made it look as though the wrapping was being peeled away. We arrived 40 minutes early, waited an extra half hour past the scheduled start, and when it finally began, the daylight still lingering in the sky dulled its impact. Beautiful in concept, but fleeting in reality.

The following morning, we struck out on foot to my favourite part of Berlin: the creative hub of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, and especially the RAW-Gelände and Urban Spree Gallery. Here, the city feels alive in colour; the walls and even traffic lights are layered in street art. Workshops are buzzing, and electronic music is leaking from doorways. I shot rolls of Lomo 800, a few frames of 120, and square pics on my little old toy camera to catch the layered textures.

Just across from the gallery was an intriguing machine; its sign said “Secret Packs!” It was ten euros to buy a sealed, undelivered, mail-order package. We had to give it a try, and it proved to be hilarious. After great deliberation, Harrison chose a package, I paid the machine, and the package dropped down. With great interest, we watched Harrison rip it open to reveal two pink Hello Kitty figures. They are going straight on eBay.

From there, I wanted to make my way to the bookshop, but didn’t want Sara and Harrison to have to follow me. So they headed back into the city centre.

Shakespeare and Sons bookshop instantly felt like home. Inside was a bagel café, a co-working space with the nostalgic glow of an internet café, and bookshelves so well curated that the sci-fi section immediately presented me with Stranger in a Strange Land. That’s the novel that inspired the name of the Grokkist Network, and my own publisher, Grokkist Press. Anita, who was selecting books that day, welcomed Salt & Seeds into their collection with real enthusiasm.

Then my phone buzzed. It was Sara. Her words stopped me cold:

“Harrison’s been attacked.”

While waiting for Sara outside the toilets at Alexanderplatz station, a man had run in and smashed a bottle over Harrison’s head. As the crowd scattered, thinking it was a terror attack, Harrison was thrown against a wall, then forced to the floor. The man tried to stab him in the throat with the remains of the broken glass bottle. Dazed and bleeding, Harrison somehow stayed conscious and disarmed his attacker. The man fled.

I rushed back to the hostel for our passports, to send images of them to Sara for the police. While I rushed across town to Alexanderplatz, paramedics were tending to Harrison. Cuts marked his hands, shoulder, head, and neck; his elbows were grazed and swelling. There was still glass in his head, but the bleeding had been cleaned away. Some big, muscular guys came over to apologise for not helping him, they admitted they had hidden in fear. Others had called the police from behind the safety of glass doors. This, I thought grimly, is the world we live in now?

We were shaken and grateful beyond measure that Harrison had survived. If he had been knocked out by the first blow, the attacker would have been free to stab him, and he would be dead now.

As it was, the attacker got an unwelcome surprise, and I hope he’s reading this now. Because you ran in, shouting, looking for a victim. You saw Harrison, head down, looking at his phone, minding his own business, waiting for his mother. So you judged him and imposed your violence upon him while bigger men ran in fear. But it didn’t go your way, did it?

What you didn’t know was what’s inside, what the young man had been through before you decided his fate. Harrison survived a horrific accident, falling from a fairground ride when he was very young. He suffered a head trauma that damaged his frontal lobe. He underwent difficult surgery and was blind for a time afterwards. When he eventually returned to school, it was like beginning again; the other boys saw him as vulnerable and he was bullied mercilessly, mainly because he refused to stay down. We were eventually advised to take him out and move him, while the bullies were allowed to stay.

He has had years of therapy and medication for physical complications, PTSD, and intrusive thought OCD, which gives him horrors in his mind. He also has Addison’s Disease, all of which he has had to learn to live with.

So when you smashed the bottle over his head and strangled him on the ground you thought you’d won, but when you tried to finish him off with that bottle to the throat, you finally saw it. He stared you in the eyes, took the bottle from your hand, and, luckily for you, he chose not to retaliate, and he let you run away. You gave him your worst, but Harrison’s seen worse horrors in his own head, and he took pity on you for your own mental health and poor judgment. Next time, don’t judge a book by its cover. As my boy has given you another chance.

In the quiet hours that followed, we made a decision: we would not visit the other German cities on our list, nor any more large cities at all. From here, we would stick to small towns and villages. We wanted quieter places where the pace was slower and the edges softer. Our next stop would be down the country to Quedlinburg and the Witch’s Dancefloor.

Berlin had given us all the extremes: beauty and brutality, creativity and cruelty. It was a city I’ll never forget, for reasons both wonderful and traumatic. But thankfully, the adventure continues.

I'll leave you with a few more pics, including, as always, lovely local dogs.

Member discussion