What is the relationship between Values and Actions — especially in reference to values rooted in Faith, in an era of existential crisis posed by climate change?

In other words, does it matter whether or not you “have faith” when you’re trying to “save the world”?

I’ve had these things on my mind recently, especially because of a series events that took place at the tail end of August — four different events that exemplified four very different approaches to ecological action, each of which made different implicit claims about ultimate values and the nature of reality — e.g. about God, the metaphysics of matter, and moral responsibility.

These different contexts laid bare various philosophical and strategic contradictions that exist in the ecological movement, and emphasized to me the essential importance of articulating our values in order to orient ourselves in our minds, hearts and bodies to the actions we take, or don’t take.

Over the course of four days, I found myself weeding a garden bed at a Christian intentional homestead in Massachusetts, and then on a panel at a secular-yet-spiritual eco-festival in upstate New York, and then on another panel with a doomsday climate theorist who says we’re all going to be dead within six years , and then I ended up in jail, as part of a protest at CitiBank headquarters — and then I ended up back in the garden.

I don’t mean for this to sound like an indulgently Nathanocentric travelogue — the adventures of the intrepid white man eco-rapper micro-influencer. There’s always a danger, when we represent ourselves and our actions in these contexts online, of being seduced by that very self-representation, and ending up confusing the realm of action, with that of ideology and identity performance.

Nonetheless, I do think it’s valuable to ground this account in my personal experience, since my own multifarious adventure over the course of these few events illustrates the organic connection between totally different and sometimes contradictory approaches to ecological crisis.

Here’s where the story begins.

I’ve been staying at a Christian intentional community in Massachusetts called Agape, named after the Greek word in the New Testament signifying the Love that God is, an overflowing love inherent in the nature of being, the love that is the basis for existence itself.

Since my persistent intellectual interest is the way our ultimate beliefs about the nature of reality inform our actual behavior, I’ve been more and more drawn to the study of religion.

Moreover, on a personal level, I’ve been feeling more and more drawn to center my own life in my Christianity. That word, and that tradition, may have surprising or even alarming associations for some of my audience, most of which we’ll have to unpack another day. But over the course of this discussion I hope that at least some of what I mean by it will become clear.

Agape Community is an ecological homestead in the tradition of Christian nonviolence, founded by Brayton and Suzanne Shanley. I recently became connected with it via my collaborations with the Catholic Worker — a movement started nearly a century ago by radical journalist Dorothy Day and radical theologian Peter Maurin. The essential idea is to take certain key parts of what Jesus says about our moral responsibility to care for one another very literally, and to act on those instructions very directly — for instance in Matthew 25 where He says ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’

Thus, the Catholic Worker tradition is all about literally treating the neighbor with the care you would accord to yourself, without the mediation of the state, or the larger apparatus of the church. — It is a variety of anarchistic personalism, where the horizon of moral action is not principally located in large-scale institutions of government or centralized technological structures, but the immediate presence of the physical Other, the fellow being whom one encounters in ones midst.

This Other may principally be your fellow human — but it can also be extended to non-human animals; even, ultimately, to what we typically consider non-sentient beings. If Creation itself is good — and indeed it is very good according Genesis 1:31 — and if we follow Christ’s principal injunction to LOVE GOD and at the same time LOVE THE OTHER with total commitment, as it were two sides of one coin (Matthew 22:36–40) — then our self-actualization will consist in giving ourselves, in agapeic love, to the world in a very direct way. Not principally by giving money to the right cause or giving time to getting right person elected, but literally giving our material selves to the moment, we who are ourselves gifts freely given by the Source.

In practical terms, this means physically clothing, feeding and personally caring for those in need, in the here and now — the migrants, the unhoused, anyone who needs it. Other, less direct kinds of actions aren’t bad or irrelevant, but they are exactly that — less direct, as an instantiation of our essence as finite, material beings who are literally made by and for Love.

This has ecological applications — for it is an act of home-building. (“Eco-” literally means home. God, I say that a lot. But it keeps being true.) For the early Catholic Worker, especially in the context of the economic hardships of the 1930s, this meant a twofold movement of caring for the indigent in urban Houses of Hospitality that housed and fed people in need, and at the same time cultivating farms outside of the cities to produce food, and inculcate the spiritual nourishment that comes along with actively participating in that process. The idea is not just to care for one another’s immediate needs, but also to create the experiential conditions of the good life, which involves an active, participatory relationship with the material substance of ones existence.

This premise is not exclusive to Christian anarchism. It has a long legacy in the history of social activism and ecologism, in traditions that draw on various bases of value. Some traditions of agronomic anarchism in fact categorically reject the premise of transcendent value that powers the Catholic Worker movement.

For instance the mutualism of a theorist like Peter Kropotkin, or the collectivism of Mikhail Bakunin, have their value-basis not in theism but in effectively atheistic perspectives on the ultimate nature of reality. This brings up the interesting point that various agents may converge on the same form of radical action for totally different reasons. We may find ourselves engaged in the same “What” while each having a totally different “Why”. Conversely, we may have the same “Why” but find ourselves pursuing or advocating for totally different “What’s” and “How’s” — even, for instance, diametrically opposed political positions motivated by the same theory of ultimate value.

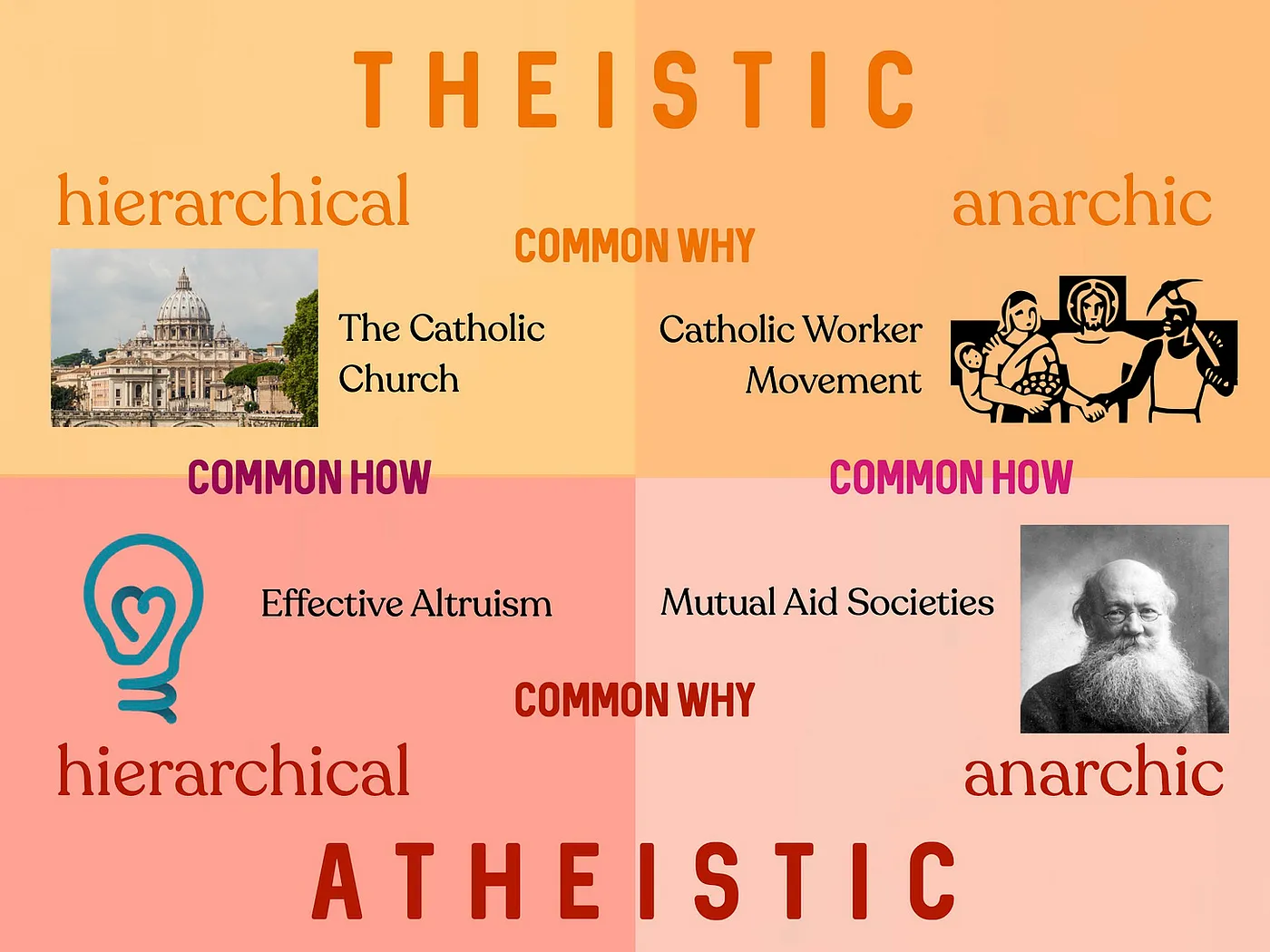

We can visualize these relationships as a chart with four quadrants. The top half shows two entities — the Catholic Church as a legal organization and the Catholic Worker movement — which share the same metaphysical perspective of THEISM, expressed in identical theological terms.

The bottom half features the Effective Altruism organization and the Mutual Aid movement, both of which are founded on ATHEISTIC philosophical perspectives.

These horizontal groupings each share a common WHY — a shared dogma about the ultimate nature of things, and a common way of expressing it, drawing on the same traditions of discourse.

But the the way they express those values in action — the WHAT and HOW that proceeds from those WHY’s, actually causes them to diverge from one another, and converge with their opposite value counterparts.

Each of these four entities could be classed as essentially charitable institutions, in the sense that they’re devoted to caring for others and reshaping society in a more caring mold. But, on the axis of praxis, the left grouping (which maybe I should have put on the right) pursues this in a hierarchical and institutional manner — the way to save the world is, raise a shit ton of money and get it to the right people who will spend it in the right way.

The grouping on the right (which is on the political left), though they make different metaphysical claims, share a common form of action, or praxis, rooted in anarchism. For them, the way to create a better world is to do it yourself, and while you’re doing it don’t trust the money and don’t trust the damn government.

These different modes don’t need to be mutually exclusive, and there are interdependencies that run both ways. But the dichotomy does bring up interesting questions about the relation between ultimate value claims and actual behaviors and political positions. This is especially pertinent in a cultural context where religion is increasingly politicized. The very possibility that there could be a radical Christian Right and a radical Christian Left implies that either one or both of those sides are misinterpreting the moral content of the Christian message, or that our understandings of ultimate value are actually disturbingly disconnected from what we actually do.

What if the form of action is itself the substance of ones faith? This leads down a whole theological rabbit hole in the history of Christianity — the tension between faith and works, between creed and deed — and down a semantic rabbit hole, regarding the relationship between language, ritual and meaning. If I use the same words and rituals to profess my faith as another, but have opposite moral behavior, in what way is it meaningful to claim that we experience the same object of faith, the same understanding of god? And we could say the same for theories that reject god’s existence, that make foundational moral claims based on the nature of material-energetic processes. Do we really ever share one another’s Why’s, or do we merely converge, or diverge in our What’s?

These considerations of language, and politics, came to the fore in the next stop of my adventures, where I participated in a panel discussion in upstate New York, at a festival called All Things Good organized by Ariana Juliet Kaminski, an alumna of my eco-philosophy course.

There I got to talk with NYC waste expert Anna Sacks, a farmer named Eugene Talbert, and Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky, a musical artist and eco-advocate.

While the festival didn’t align itself with any explicit value perspective, I would describe it as “secular but spiritual” — the tabling offered a syncretic array of reiki, crystals, and other approaches to holistic wellness, a spiritualistic overlay that has become familiar to me from other events in the ecological space. I encountered friends there who are active in the movement to legalize psychedelics, in contrast with Agape, which is a sober community.

Much can be said about the role psychedelics may play in cultivating eco-spirituality as an underpinning for social and behavioral change, a territory currently being explored by Marissa Feinberg’s Psychedelics for Climate Action; this has also been explored by Daniel Pinchbeck, who will reappear later in this account. What is at stake in the difference between spiritual practice induced by psychoactive substances, vs. practices grounded in systems of thought, such as traditional religion? Is the key to unlocking ecological consciousness more readily found in the physical entheogen, or in sober relationship with a mystical sacrament — in the acid tab, or in the communion wafer?

Alongside these contrasts, the ensuing panel discussion impressed upon me once again just how much variation there is in the types of approach to ecological regeneration. Not only are there different, and sometimes opposing political and spiritual strategies, as discussed above, but there are different and sometimes clashing tones.

On this panel I found myself asserting the personalist, anarchistic views expressed above, and advocating for radical love expressed in firsthand, devotional cultivation of the soil. I’ve been Catholic Worker pilled; all I want most is gardening and god.

But there are other dimensions to the urgent ecological situation that can make such a wish seem ineffectual and naive. DJ Spooky, whose clarity and acumen I admire a great deal, put much more emphasis on large-scale infrastructural and technological solutions, and accordingly focused on the large-scale political changes — especially the next presidential election — that are necessary to bring them about.

Which of these is more important? Guerilla Gardening or Political Mobilization? What you plant, or who you vote for? It’s easy to say “they’re both important” and they are — but it’s also important to emphasize their divergences.

There are some who say that DIY, material-action ecologism — growing your own veggies and so forth — may be a good way to find peace while the world burns, but it’s still gonna burn — that is, unless we can get the right people in office, especially in the White House, and hold the major corporations accountable.

There are others who say that institutional political action may seem to make a difference, but really doesn’t — because the people who actually come to power from either major party are mainly going to maintain the status quo, and so the world is still gonna burn — and since it is, it would be good to have some of your own veggies planted while it all falls apart.

Again, there is not a true binary between these — they are related, and both forms are necessary. But one way that the dichotomy makes itself felt is in the form of political discourse that attaches to each viewpoint, and the social identities that in turn attach to those politics.

DJ Spooky, for instance, because of his emphasis on political challenges, chose the phrase “Fuck Trump” as his final remark on the panel. This makes sense; and this is a phrase one hears in eco-activist spaces with some frequency.

While I share his revulsion retrogressive ecological policies of Donald Trump, I increasingly feel strong reservations about phrases like this — not because it’s not morally justified, but because it converts no one to the ecological cause. From my own increasingly personalistic perspective, my ally is not the person who votes the same way as me, but the person with whom I share actual, physical forms of belonging — shared systems of food, waste and shelter. There is in fact the potential for a whole eco-revolution based not in macro-level political identity, but in material collaboration in building hyper localized food and energy systems.

The conservation movement, when in began in the mid-20th century, was originally also a conservative movement. There are still aspects of this — there are rightist groups and individuals that devote themselves to conservation, and to ecologically minded design solutions like permaculture — though most of them reject the very premise of anthropogenic climate change.

The fact that our forms of political belonging have been so far divorced from our forms of material belonging is another iteration of the slippage between forms of value and forms of action that we examined earlier in the context of religion. Since religion is so much less central in our culture that at other phases of civilization, our religion has itself become politics, and our politics has become religion.

But there is a deeper meaning to both of those words that can be recovered — by this I mean religion in the etymological sense of binding one another together again, reflecting the root meaning of the Latin religio — and politics in the literal sense of interacting with one another in the mutual interest of the shared space of belonging, reflecting the root meaning of the Greek polis.

But what if none of this matters anyway — what if either course of action, whether institutional or personal, political or religious, is a lost cause — because the world is actually going to burn, and it’s actually too late to stop it? This brings me to the third stop on my value-action odyssey, an event in New York City that was ominously titled ARE WE DOOMED?

This was a conversation with a group of relatively well known writers and theorists — Daniel Pinchbeck, Douglas Rushkoff, Doug Henwood, Guy McPherson, and Vicki Robin, and me.

As the title would suggest, the through line of this panel was the theme of extreme climate pessimism. The most notoriously pessimistic of these is Guy McPherson, who promotes extreme, and extremely thoroughly researched theories of Near-Term Human Extinction. He is known for predicting human extinction by the year 2026 — a date which he has since then generously pushed back to the year 2030.

This was a challenging context. First of all, because I was a little worried I was out of my league. These were well established academics with years of research, publications and credibility, and they seemed to be in general consensus that the kinds of solutions discussed above — whether motivated by secular or religious in their ethical motivation — are meaningless in face of the inexorable economic and physical processes which we are powerless to stop, and that they’ve been studying for years.

Underlying this thread of pessimism however was another through-line — not only were these thinkers skeptical about the possibility of averting the total collapse of civilization, there also seemed to be a general sense of skepticism about making any grand ethical value claims in the first place. Earlier I was discussing how we do or don’t arrive at the same “What” by virtue of our common “Why” — but in this context, the implicit assertion seemed to be that there is no Why in the first place. The tone was not one of entrenched moral certainty, as it was in the previous two contexts, but a more circumspect, bird’s eye view of the cosmic relativity of all life and human endeavor.

I’m not saying that characterizes the view of any of those writers, whose metaphysical and ethical perspectives are complex and varied. Rather I’m observing that different cultural contexts embed much different implicit theories of value, and these different perspectives entail different attitudes to how we should address social and ecological issues. To put that more plainly: there’s a big difference in vibe between religious anarchists living in the woods, new agey progressives in upstate New York, and academic intellectuals in New York City. Perhaps that’s obvious. But it’s important because those different vibrations, those different aesthetics of identity, lead us to espouse different ecological behaviors, and to advocate different positions — even the position that we’re doomed no matter what we do, which may in fact lead to doing nothing at all.

On the face of it, I reject the radical assertion that we are in fact “doomed” — I don’t think that inevitability is reflected by the current data as I understand it. That said, it is significant, as my friend Baba Brinkman observed, that very smart people who are very well researched do in fact feel that it’s likely. There is a profound epistemological problem with climate change — there is so much data, involving so many complex relationships among physical systems, that nearly all of us activists who have located our efforts, careers and identities in the struggle to stop it, are relying on secondary and tertiary constructions of that data. Not everyone can be a climate scientist and philosopher and activist all at once — though perhaps if each of us put more emphasis on integrating those observational, interpretive and expressive functions, the culture of climate action would obtain more coherence.

Curiously, in spite of the concerted assertion of hopelessness on the panel, we kept coming back to the theme of LOVE. In fact, Guy, the most doom-oriented of all of them, was the most emphatic about Love. Will Love save the world? No, he would argue; but we should love anyway.

How is this Love different from the Love articulated in the Christian context discussed above?

One way of understanding this is by considering the difference between finding meaning and making meaning. Some of the panelists’ remarks seemed to imply that there is no inherent meaning or value structure in the nature of reality. Values exist but they are subjective; a loving attitude can diminish the pain we experience as the world crumbles around us, but love itself is not some cosmic force that is sufficient to save us. Other panelists seemed to espouse a more spiritually assertive perspective, implying that Love has an objective reality — such that even if the world crumbles, we abide in that love, and it gives meaning to the crumbling, as the precursor to whatever comes next in the cosmic evolution.

In this connection I found myself once again discussing the early Christians. Many of the early Christians also believed, for much different reasons, that the world was about to end — that the apocalypse was literally, physically imminent. But because of that, it didn’t become a matter of throwing their hands up and not caring about how to live — but rather a matter of letting go of everything that’s not important, and living radically for one another, in community. As it says in the book of Acts (2:44) — “and they held all things in common.” Another panelist, Vicki Robin, iterated on this same theme.

In this way, there’s yet another strange crossover between apparently contradictory constructions of value. Precisely because there’s no hope, we possess hope. “Hope” is often misunderstood as the anticipation of a desired outcome — but it’s subtler than that. Hope is acting in an attitude of possibility — the attitude that all good things are possible even when they seem impossible. Hope in the mystical sense already possesses its object even in its apparent absence.

Precisely because the kingdom of God transcends this world and is always both beyond this world and within it, we should attempt in the here and now to build it. When it comes to Kingdom Come it’s not a matter of if you build it He will come, but rather because it will come in the form of being spiritually already here, you are enabled to help build it materially while you’re here, even when it seems it’s falling apart in your hands.

What does this have to do with Climate Change? My takeaway from the Doom panel was this. — Even if it seems impossible, or paradoxically, precisely because it’s impossible, we must build a new world — “build a new world within the shell of the old”, as in the phrase of the historical labor movement. The old world will pass away — life as we know it will change — but this is not just a tragedy, it is in fact the precondition for that new world, as death is the precondition for resurrection, and rebirth.

But not all forms of building involve literal building up; sometimes building involves tearing down. This brings me to the fourth and final act in my recent adventures, a protest action that I joined with an organization called GreenFaith, in the conclusion of a series of actions called the Summer of Heat.

I sometimes have reservations about protest in the modern context. I sometimes worry that it’s performative in a way that’s not effective and that it actually estranges the people that needs to convince. While it’s been an essential aspect of historical struggles for justice, something about the ideological conditions of the Digital Age have made me question whether it can still be effective now, when technologies of self-documentation and self-presentation such as social media change what it means to publicly demonstrate.

In How to Blow Up a Pipeline, Andreas Malm writes about the apparent limits to the effectiveness of peaceful protest in the climate movement, arguing that while public demonstrations have succeeded in increasing the visibility of and public consensus about climate change, they have not adequately moved the needle on government and corporate action. Moreover, the very performance of public dissidence itself is often subsumed into the dominant cultural matrix as one more distraction offered as an image on our devices.

Nevertheless, I felt drawn to participate in this action precisely because it’s rooted in faith. Like several other actions of its kind this summer, this was a demonstration of clergy and lay faith leaders from various traditions, obstructing the entrance to CitiBank, the largest new investor in fossil fuels since the Paris Climate Accords. It was led by my friend the Rev. Chelsea Mac, among others.

Why did this feel qualitatively different than other protest actions to me?

Perhaps because the literally prayerful attitude in which it was carried out gave it a different spirit than one sometimes encounters in these spaces. To protest is literally to be a witness for — and that act of witnessing connects to the prophetic tradition in the Old Testament sense of the prophets, the figures who arose to articulate the injustices of the existing social conditions. Prophetic witness is distinct from other forms of critique in that its makes its critique explicitly on the basis of a transcendent locus of value — the Source, the Spirit, the Presence, the All in All. Hence a sense of the great Cosmic Why permeates every aspect of the protest action, the What.

Because of that, another thing that felt distinct about it was that it was not so much accusatory as invitational. The rhetorical emphasis was not “Citibank you’re evil” but “Citibank you’re powerful, and we invite you to repurpose your resources toward securing the wellbeing of the sacred earth, and to operate in alignment with the Ultimate Concern and ground of being.” (That wasn’t the chant — that would be too wordy — but that was the implication.)

And so there we were, barring the doors of Citibank right as it opened, with all the employees lined up around the block, unable to get in.

We weren’t there for more than five minutes before we were arrested — two interfaith leaders, a presbyterian minister, an Episcopalian priest, a Quaker, two Buddhists, a jew, and me, and an array of other folks. Actually one of them turned out to be an atheist. One more generative contradiction of faith, value and action.

I found some time to reflect on all this in my cell, as one does. At first I had a distinct impulse to photograph myself there — like, What up everyone, I’m in jail — a sort of automatic reflex of the self-representational matrix of hyperreality in which we live — but of course I couldn’t, because they confiscate your phone.

And because of that, and because of everything else about the context, it became a very luminous experience.

In my cell, I felt a sense of peace, even of elation. I felt extremely physical — a sort of ecstatic sensuousness. I could hear voices from the cells adjoining mine talking about theological and spiritual matters; while from the women’s cells through the other wall I could hear singing, the same songs we had sung outside. And I sat and lay on my slab and prayed. I felt, as the saying goes nowadays, very present and in my body.

It was then that I realized that this was not a performance — except in the sense that even in solitude one performs even for oneself, for the Source Itself — but I realized that being a witness is not so much a matter of stating an idea as of being a body, letting one’s body itself be a witness for the sacredness of the living world.

And there, in that moment when the gesture of self-representation was perfectly impossible, where there was nothing to write with and nothing to share, there where the virtual vanished, where the ideology of it all dissolved in the immediate starkness of a physical prison, there in that cell, I felt quite free.

In my cell I felt freedom from self — by my self alone, without my cell phone, with no selfie, I was self-free, I felt my Self, free.

That may sound like a romanticization, and an expression of privilege, and in a sense it is — not everyone who gets put through the system gets treated with “courtesy, professionalism and respect,” not everyone is there just long enough to pray and ponder and then go write about it, and not everyone chooses to enter that system as a deliberate ideological gesture, while being connected to an adequate support network as I was, including a team of people running jail support and contacting lawyers for the cause.

Most people have no support. And many who have gone to jail for reasons of prophetic resistance are still there.

It was in the book mentioned above, How to Blow Up a Pipeline, that I learned about Jessica Reznicek and Ruby Montoya, two Catholic Workers from Iowa who went ahead and set fire to a section of the Dakota Access Pipeline — both of who are still in prison. It was learning about their radical act — an act of faith, expressed in the destruction of property for the preservation of the sacredness of creation — that set me on the course I’m now on today, seeking to discover what it means for me to radically live my faith in my ecological actions.

What is that faith? I believe in God, the Source of all Being, and I believe that that Creative Source entered Creation and remains in Creation, and will once again restore that Creation, and I believe that the Spirit of that Source courses through all of us, and I believe it calls us to care for the created world and for one another as a manifestation of the Source’s own goodness, and in so doing to return to our true selves, and to sing while we do it.

…But why does any of that matter? Why do you need a creed? Can’t we just do the stuff?

For me the faith part matters because it guides me in terms of the reason behind what my actual actions are. The creed is not mere ornamentation on the surface of the deed; rather it provides the moral structure of the doing itself; it is not a mere “sense of identity”, rather it is the transcendence I follow so that actions do not become a mere identity performance — it invites me into action in such a way that I transcend myself. I do not attain that transcendence by doing any particular action — I am not “justified by works” — but only in my actions is my faith substantiated.

What defines your religiosity — your faith? — This question applies whether or not you ground that faith in a particular religious tradition. Is it defined more what you PROFESS, what you believe in, or by what you DO?

Some celebrities and influencers have recently been turning to religion, as the post-post-world world grapples with the inadequacies of a worldview that militates against the reality of ultimate values. But what does this mean for their DOING? What does it mean to adopt and profess such a creed, whether on the right or the left, especially as religious identities become coterminous with political ones, such as in Christian nationalism?

But beneath these battles of doctrine and identity is the actual, material ground of the embattled planet. It is in the theater of that actual doing that our performances of self reveal the real values around which our characters are coiled. That revelation applies to Christians, to Buddhists, to New Age Spiritualists, to one and all — are we here for ourselves, for our festivals, our services, our professions, our profiles, or for the Other, the great Other the whole world is, equally with ourselves?

It’s in the consideration of these things that I find myself at Agape Community here at the onset of Fall. It’s a place that’s dedicated to that holism, and provides those who visit with an opportunity to enter into it.

We don’t have enough arable land on the planet for every person to have as much space and peace and quiet as I now have access to at this moment — but everyone does deserve it. This why my own value structures increasingly lead me to a conviction that we need to create pipelines of relationship between the cities and rural intentional communities like this one — pipelines of relationship to replace pipelines of oil and gas — “agronomic universities”, as Peter Maurin called them. The human future as I see it is centered in the eco-city, maximizing food production, energy capture and storage in urban environments and their immediate outskirts — while at the same time with providing every citizen with access to intentional outposts like this one, for their spiritual wellbeing.

But the way to get to such a future, or to any desirable future, depends on greater strategic coherence than the ecological movement currently has; and that coherence in turn depends on a shared articulation of value — a clarification of our intertwined What’s in reference to our overlapping Why’s.

At the time of this writing, this very community — Agape — is seeking new members and new connections. On October 5th, 2024, they’ll be hosting their 42nd annual St. Francis Day festival, a gathering of faith-based activists from throughout the Northeast to confront precisely the crises I’ve been discussing here, and to celebrate the miracle of being here in creation in the first place. All are welcome.

Do you need to be “of faith” to be part of a community like this? This community is grounded in Christian nonviolence; but its practice and outlook is inclusive and diverse.

The word Catholic literally means universal. I believe that relationship with God in community is such that your specific understanding of that ultimate being, that source of all value, is at once intimately personal AND radically shared, even if those two things may sometimes seem to be in contradiction. — But the contradiction is only apparent; for God, unlike us, is both Personal and Absolute.

The form of the faith is not more important than the works to which it leads; but the works are made holy by the shared form of faith — Faith IS work. — And it is not just a synthesis, it’s a simultaneity — Matter AND spirit, Creed AND Deed — “For as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is dead also” (James 2:26).

And we are not dead; and so let us, we who are creation, work.

Member discussion