It took a particular sort of mind to love computers in the early days.

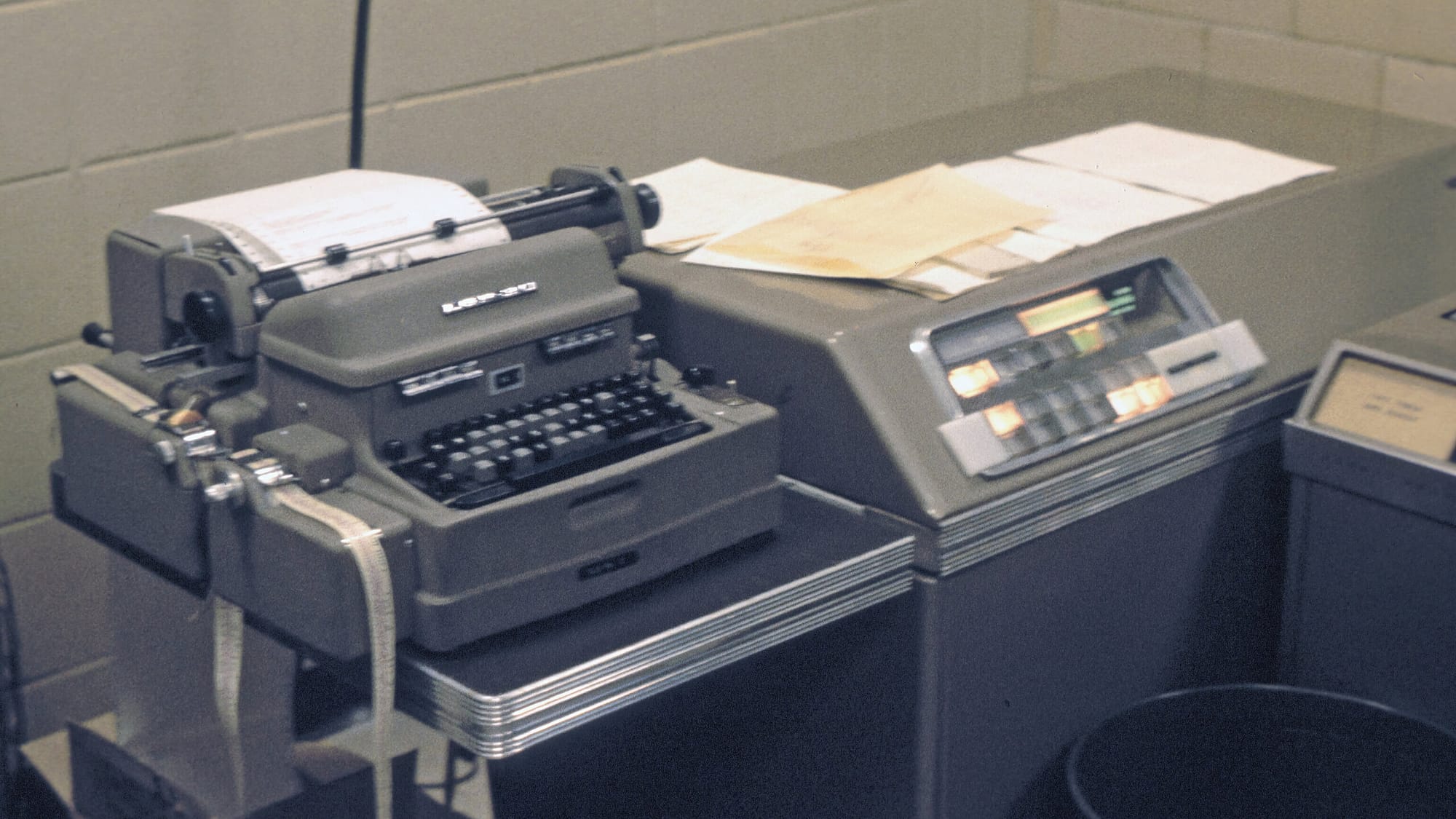

Large clunky machines that demanded painstaking data entry (first through punch cards and later pure code) were not for the fainthearted. Only those who saw beauty in numbers really got computers. Edward Lorenz, the architect of chaos theory, was one of them.

Described as a ‘genius with the soul of an artist,’ Lorenz initially trained as a mathematician. But, having spent the Second World War working as a weather forecaster for the US Army Air Corps, he chose to continue in meteorology.

During the 50s and 60s, employed as a research scientist at MIT, his background in mathematics allowed him to explore how computers could create more accurate longer-term forecasts.

Chaos theory came about through a random glitch in his work. One day Lorenz wanted to examine a weather simulation in more detail. Therefore, he found a line of numbers that the computer had printed out earlier in the sequence, and entered them back in. Then he re-ran the simulation and went for a coffee.

When he got back, he did not find a more detailed version of his earlier simulation. He had a drastically different result altogether.

After discounting computer malfunction, he realized what was happening. The computer did its work at six decimal places, (e.g. 1.123456) but the printout he had used to replicate the data had only recorded it to three decimal places (e.g. 1.123).

He had thought any amounts missed here would be negligible, but it turned out that even tiny mathematical fluctuations could result in massive differences in the way simulated weather patterns played out.

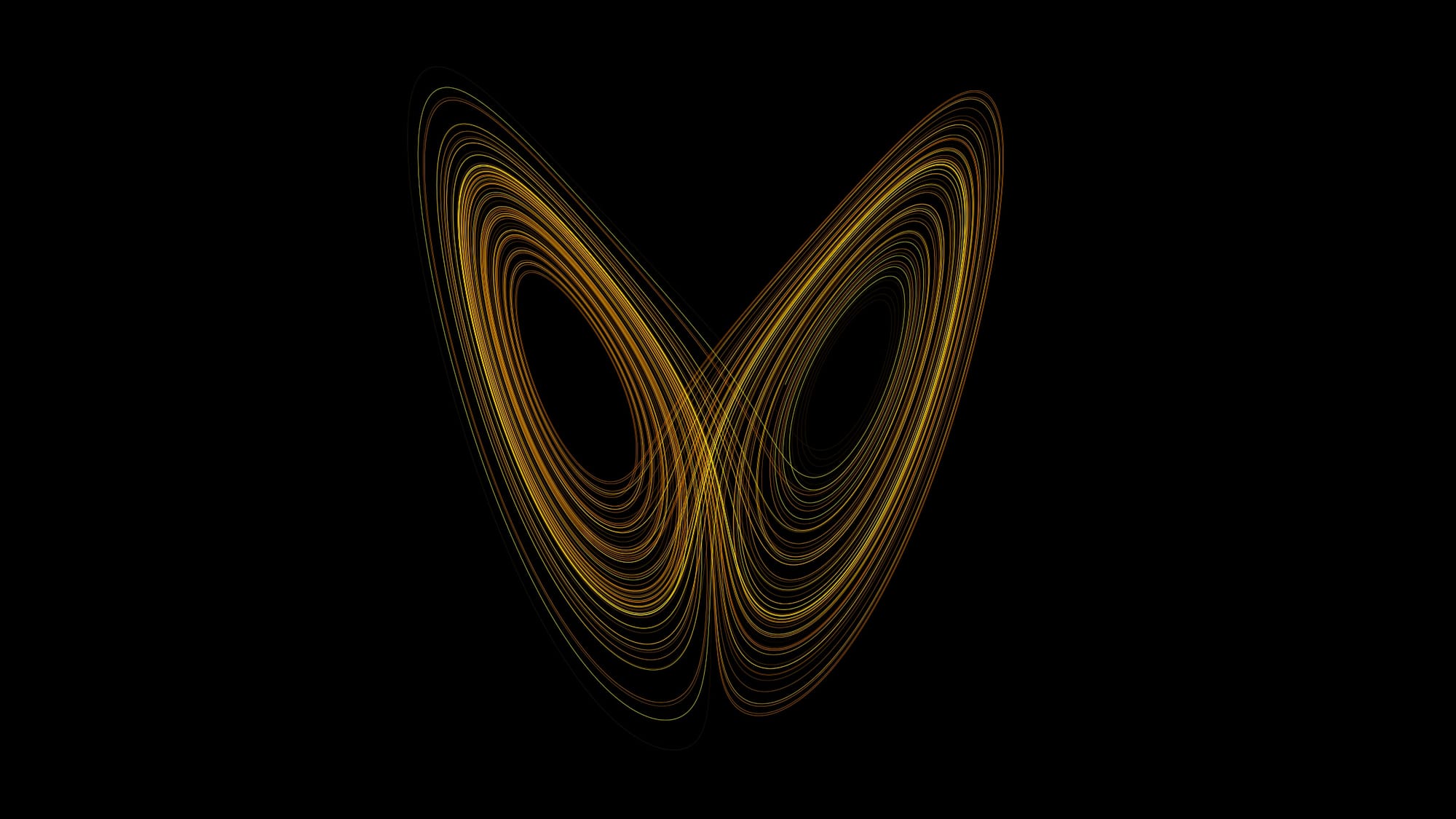

After working on this for a while, Lorenz was able to show that although there was an overall shape to the weather, how it played out was far more variable than previously thought.

When visualized as trajectories given infinitesimally different coordinates, it ended up looking like a butterfly. That butterfly shape then helped give rise to the metaphor that has since defined the field Lorenz had just created.

Nowadays few lay people understand chaos theory, but most of us have heard about a butterfly that flaps its wings over Africa and creates a storm in the Bahamas (or variations thereof). The butterfly effect, as it is called, is a wonderful way of explaining the way microcosmic events can have macrocosmic results.

I first heard about the Butterfly effect sometime in the 90s. I was in my 40s and beginning to grapple with the way that life was not as straightforward as it had seemed in my 20s and early 30s.

You tried to do good, and it had no effect while people around you succeeded through dodgy means. You poured your heart and soul into trying to teach people the important stuff, and it seemed to mostly run off them like so much rainwater off a duck. The metaphor of pearls to swine seemed apt, though unkind, but I was struggling to find a better one.

Then I discovered the butterfly effect and suddenly realized that I was that butterfly.

I was flapping. Hard. Trying to stay in the air and avoid getting swatted, blown or eaten. However, I reasoned that even if I was the very butterfly that caused a Bahamian storm, I could never have known.

That butterfly would have appeared no different to all the other random butterflies flitting around Africa and getting on with life without a trace of existential angst. If they stopped to ask themselves whether they had, in fact, managed to cause a storm, they would probably get so distracted that they would nose-dive into the hard African dirt.

No, the way to cope as a butterfly would be simply to keep on flapping. Doing what you do, and not worrying about whether you were achieving a result.

The only certainty was that if you stopped flapping, you would cause nothing whatsoever.

The way to cope as a butterfly is simply to keep on flapping. Doing what you do, and not worrying about whether you're achieving a result.

The only certainty is that if you stop flapping, you'll cause nothing whatsoever.

Since then, I have tried to remind myself that I cannot necessarily know whether the things I have done have made a difference. I have had former students say to me “I always remember what you said about….” Usually I have no clear recollection of this. Often it was a throwaway comment, but somehow it stuck. The butterfly effect at work.

The world is full of people who want to improve things. People who want to make a difference. Most of them are young, because at some stage most of us get sick of trying to make a difference without seeing any tangible result, and thus become old and cynical.

We are all so conditioned to do something for immediate reward. We want to make grand gestures and bask in the glory of success. The Butterfly effect reverses this.

You cannot know the effect of your actions. Possibly they will go nowhere. Probably they will go nowhere, and even if they defy expectations and achieve something, you likely won’t get the credit. But there is still that chance, however small, that something you do will snowball, and create meaningful change somewhere. You may never know about it, but nevertheless you started it.

Being a butterfly means you can retain some faith that your life is not entirely meaningless, and that your actions, on however small a scale, could make a real difference. It is a way to keep on moving forward, despite the evidence tugging you towards inertia.

Butterflies are not large grumpy animals with big teeth. They are small, beautiful, and they get through a lot in a short time. Hence, whenever I start feeling despondent about things not turning out as I had hoped (and mostly they don’t), I simply remind myself that I must just keep flapping.

And that I don’t need to snarl and bite to make a difference.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion