Victoria Park was a wonderful setting for cricket.

It was a huge playing field surrounded by mature trees, and on summer Saturday afternoons it was teeming with cricketers. Four or five games would be happening at once, with the best areas (called wickets) being the preserve of adults. Out on a far corner of the ground you could find us juniors.

By the time this story begins, I was past dreaming of being an international cricketer. There were people who were better than me at bowling (that’s like pitching for those who don’t know cricket) and at batting.

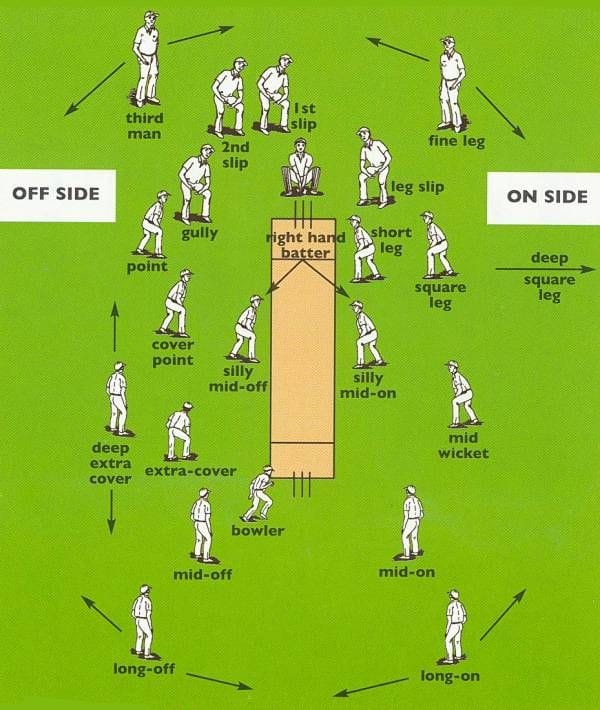

But there was one skillset where I could match anyone. Not that anyone wanted it. Standing three or four meters from a batsman, 45° in front of them, was a risky place. That’s why the position was called “silly mid-on”. I kid you not.

Batsmen hit a cricket ball hard. I still have a flattened bridge to my nose as proof. That happened when, instead of ducking, I opted to try and catch a lustily hit ball and it crashed through my hands and laid me out. But generally, I had good reflexes.

This particular day, I was standing waiting. Behind me the bowler sent the ball hurtling towards the batsman. Suddenly I found myself diving sideways, just as the batsman began winding up to hit the ball.

He whacked it hard.

Imagine, for those who don’t understand cricket, how hard a fourteen-year-old can hit a baseball. It was going at that speed – and a cricket ball is the same hardness, too. Yet somehow, there I was flying full length and plucking it out of the air maybe two meters from where the batsman had hit it.

Afterwards I had no idea how I had done it. The time the ball would have taken to go from the bat to where I caught it was negligible. I must have started my dive well before the ball had even reached the batsman.

So how did I know the exact place and time where the ball was going to be within my reach, and how did my body commit to the dive without me really knowing what I was doing – or consciously agreeing to the proposition that “yes, I’m comfortable with randomly jumping in front of a hard object flying at great velocity”?

The answer I eventually arrived at was that I was using intuition.

But I had to figure out what exactly ‘intuition’ meant. This was something that I wrestled with for a long time, because people back then tended to treat it as something rather mystical.

Eventually, I concluded that, instead, intuition must be a very fast non-verbal type of intelligence. My reason for regarding it as intelligence was quite simply that I didn’t know anyone who intuited things that they were neither good at, nor invested in. Think of it as ‘into-it-ion’.

In my generation, women were generally regarded as more intuitive than men, particularly about things like relationships. Sadly, while women thought deeply about such things, men were not brought up to do so. Hence our general cluelessness in sensing when it was more appropriate to offer words of support than to dole out advice.

Perhaps that male default is changing (I hope so), but the point is that if you want to be intuitive, you had best put in some hard study first.

I have subsequently found that my ad hoc definition of intuition is not far off how psychologists define it. But the important thing for me is that thinking of intuition as a form of intelligence helps me to trust it.

Thinking of intuition as a form of intelligence helps me to trust it.

When I get that intuitive sense of certainty about something, I know I need to drop everything and get on with it. Like with my writing. If I leave it until later, or if I were simply to sit down to try and write from scratch, it doesn’t flow.

Instead, I am always on the lookout for ideas that trigger that unmistakeable feeling of being both right and do-able. Once I have that feeling, I can write with confidence. I don’t need to consciously know the outcome either – that sorts itself out.

Mind you, that feeling of certainty only gets you a first draft. It doesn’t mean that everything will work automatically. Craft, and good editing are still essential, and even a small flaw in this can lead to problems.

I learned this, too, when catching that cricket ball at Victoria Park. Remember how I was sailing gracefully through the air having plucked the ball from its trajectory? Well, that turned out to be the easy part. Then came the fall.

In this case, the force of the ball had pushed my hand so far that when I landed, it was the back of my hand that hit first. My fingers automatically opened, and the ball spilled out. My intuitive athleticism still ended up with a dropped catch.

As a young cricketer, I had been studying batsmen for some years, and I must have somehow been able to read the future trajectory of the ball from an understanding of the batsman’s body language. I had, in other words, seen enough cricket shots to intuitively predict what was about to happen.

Unfortunately, I had no such prior experience to guide me on how to hang on to the ball when I landed.

Perhaps this is why it is so much harder to end a piece of writing than to begin it. Intuitive certainty helps you get started, but it’s hard-earned experience that finishes it off properly without dropping the ball.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion