During the 1970s, my mother established herself as an expert on Children’s Literature. She had recognised the genre’s recent flowering and worked tirelessly to promote good literature to parents and teachers. Then she became a children’s book reviewer for the New Zealand Herald, and new books immediately poured into our household.

My brother and I became her crash test dummies, reading these new books and reporting back to her. Authors like Lucy Boston, Ursula le Guin, Madeleine L’Engle, Leon Garfield and Diana Wynne Jones all gave hours of pleasure and left me with an abiding love of children’s novels – books with big themes, exciting plots and a paucity of sex and overblown description.

These were not books that set out to teach, but they taught. Fantasy books allowed you to deal with the battle of good and evil. Historical books took you to other places and times and encouraged empathy across the divide. I enjoyed the stirring stories of Geoffrey Trease and Ronald Welch, but my favourite historical novelist by far was Rosemary Sutcliff.

I had a rough time socially once I left primary school. At times I felt ostracised and had few friends. Basically, I tried to endure school so that I could get back to the sanctuary of home, the golf course and books. And of all the literary heroes I encountered, Rosemary Sutcliff’s spoke the most to me.

They were often dealing with trauma: the loss of a military career through injury; the loss of your entire family and being thrust into slavery; failing the test that allowed you to become a warrior; being driven from your home because you were thought to have the evil eye.

In almost every book the hero had to work through these trials and, in some way, make peace with them. I lived every twist of their journeys. I was them.

In almost every book the hero had to work through these trials and, in some way, make peace with them.

It wasn’t until later that I found out why Rosemary Sutcliff’s heroes embodied this mix (of scarred, vulnerable yet ultimately resilient) that I so responded to. Her own journey had been every bit as difficult as theirs.

As a child she suffered from Stills disease – early onset rheumatoid arthritis – which left her in pain and with severely limited mobility. The palpable sense of isolation and being different that permeates her novels was very much autobiographical. But so was the determination and the sense of needing to behave justly in the face of whatever came your way.

I haven’t been able to discover that Sutcliff was particularly Stoic, in the philosophical sense, but stoicism (as in being courageous, uncomplaining and virtuous), resonates through her books.

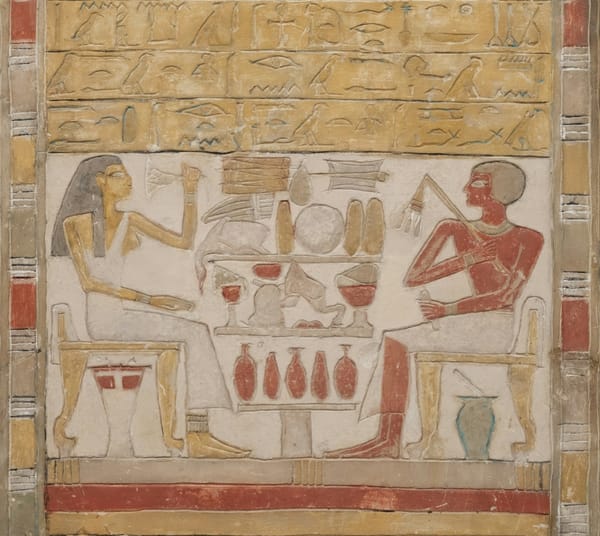

Some of her most famous were set in the Roman world, where stoicism was perhaps the dominant philosophy. It is therefore natural that her characters would display such qualities, and I, at all events, was nourished by them.

I survived my teenage years by trying to display fortitude and controlling my own reactions to situations, with Sutcliff’s heroes acting as a yardstick. I would go as far as to say that I owe much of my approach to life (and probably my sanity too) to her.

I survived my teenage years by trying to display fortitude and controlling my own reactions to situations, with Sutcliff’s heroes acting as a yardstick.

It's not just the heroism of the books that has helped me, though. Sutcliff usually has some question lurking under her stories, and one of these, particularly, affected me as an educator.

During my first year as a teacher, I reached for one of her shorter books as a way of de-stressing. That year was one that required all my fortitude as I tried to navigate teaching in an open-plan environment. I certainly needed something for the soul.

The Witch’s Brat provided that. It’s a story about an unwanted, crippled child who gradually makes a place for himself as a healer in medieval Priories. But the underlying challenge for this hero was to find out what sort of healer he would become – one who bled with his patients, or one who stood aloof and did his best for them.

This formulation really resonated with me as a teacher. I had recently looked around the staffroom and realised that I was observing a group of people who were living six inches behind their eyes. On the other hand, I wanted to be that rare teacher who could bleed with the students and live their journeys beside them, but I was not sure if I could survive the toll that would take.

… I wanted to be that rare teacher who could bleed with the students and live their journeys beside them, but I was not sure if I could survive the toll that would take.

The book seemed to resolve itself with the character accepting that, while he could not bleed with every patient, he could invest fully in some. That seemed like a compromise I could make, and it helped me negotiate those early years of teaching.

In 1992 I was reflecting on Sutcliff’s role in my life and felt a particularly strong urge to write to her and tell her how much she had helped. With a busy job and young children, however, I didn’t get around to it immediately. A couple of months passed by, and then I heard on the news that she had died.

It was a salutary lesson in why one should follow up on those sudden promptings to gratitude, and I have always regretted that, despite her undoubtedly having many fans who did tell her how much she had meant to them, I was not one of them. Still, there was nothing to be done. I had to accept my omission stoically. Writing this, though, is perhaps one way of atoning for it.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion