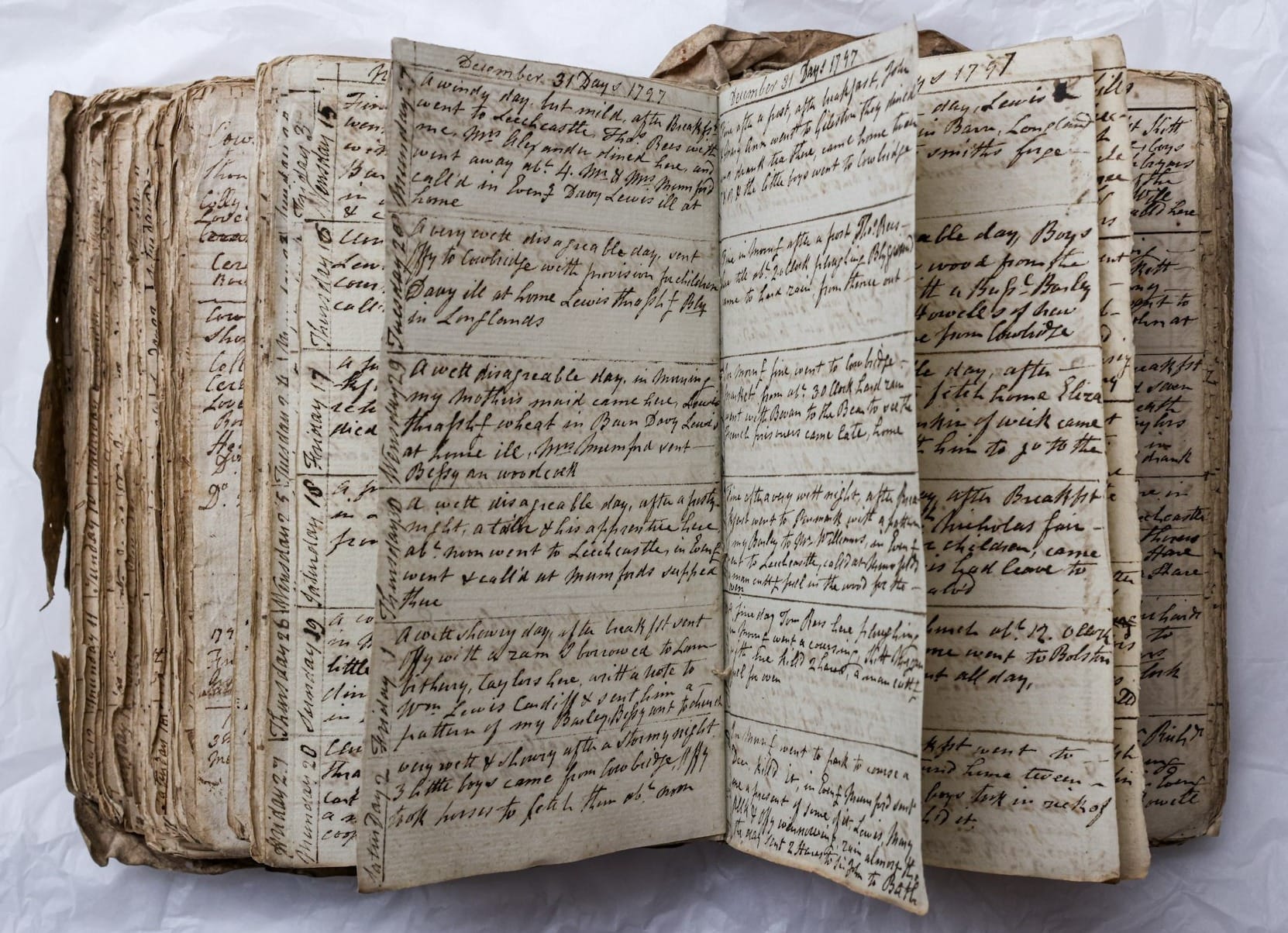

It was 1949. Looking down from an aeroplane flying above London, a pilot might have spied a small fire burning in a Sanderstead backyard. My mother, with the lightened heart of one who has just finished her final exams, was burning her palaeography notes. She had just sold all her palaeography textbooks. As far as she was concerned, palaeography was history.

As far as she was concerned, palaeography was history.

Back in the 1940s, anyone trying to study English at London University had to learn palaeography – the study of ancient scripts. Palaeography allowed you to read Beowulf in the Anglo-Saxon and Shakespeare in his handwriting.

The problem was that, while my mother enjoyed Beowulf and Shakespeare, she was quite happy to read them in modern editions before doing a deep dive into T.S. Eliot, W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas. Her passion was the moderns, not the ancients.

It would have surprised her to know that one of her sons would come to curse that bonfire and her ready shedding of her textbooks.

As a calligrapher, I am fascinated by ancient scripts, and would have appreciated access to what she studied, instead of having to haunt online bookstores to try and access the material that she had at her fingertips. But I can’t blame her too much. I did something similar.

I was perhaps fourteen and finding my English class a bore. I enjoyed English, providing it meant writing stories. I did not enjoy English when it meant studying grammar. Subjunctives, infinitives and prepositions were not my happy place. I didn’t need them to be able to write.

Writing, as far as I was concerned, came from reading and then doing what came naturally. Grammar got in the way and stopped the flow. And so, somewhere in a prefab at the back of Rangitoto College, I resolved to simply ignore grammar. I would not need it, and it was not worth the effort.

And so, somewhere in a prefab at the back of Rangitoto College, I resolved to simply ignore grammar.

Unlike my mother, I got to experience the error of my ways for myself. A few years later, I married a Dane and moved to Denmark. I then had to learn Danish and was immediately immersed in grammar. And it was hard. It wasn’t that I had rust. There was nothing much to be rusty. Grammar simply slipped out of my brain without adhering to anything.

Eventually I managed to pick up the language, but it was via usage rather than grammar. My written Danish is still error-prone because, while grammatical errors can be semi-masked in speech, they are there for all to see when you write.

All of which shows just how easy it is to limit one’s future options. I could write well and therefore believed I could do without grammar. My mother (despite her wayward handwriting) could do palaeography but didn’t think she needed it. We were both cocky enough to think we could write our own future, and that the script would not involve palaeography or grammar, respectively.

If ‘the past is foreign country’ then it would pay to think of the future as one too. Except more so. We cannot know what is involved in traversing that new land, or what will be required of us to do so. But deciding ahead of time that we are not going to need certain tools is simply foolish.

We cannot know what is involved in traversing that new land, or what will be required of us to do so.

I now prefer to make no predictions or assumptions and simply educate myself as broadly as I can. Then the future can do its worst. The old Scouts’ motto of ‘be prepared’ carries a good deal of practical wisdom.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion