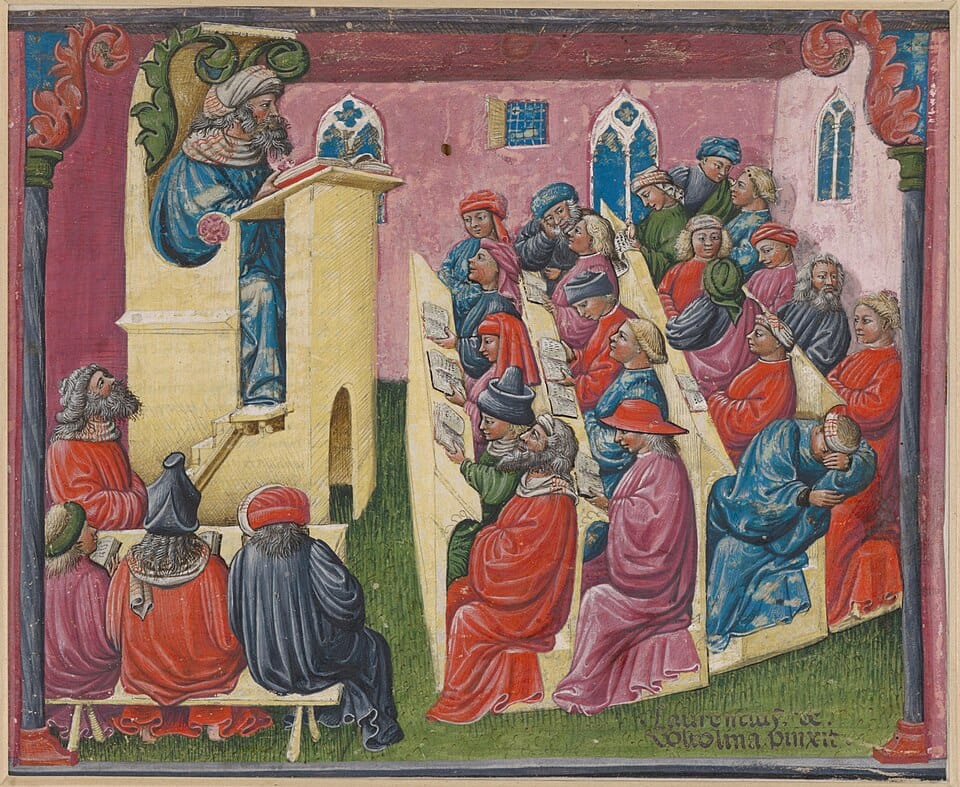

Somewhere around 1350, an artist called Laurentius de Voltolina painted a miniature of a lecture theatre at the University of Bologna. In it, a lecturer (described variously as either Henry of Germany or Aristotle!) sits at a lectern reading aloud from a book.

His students are ranged across four rows of seats. The ones at the front are following the text attentively. The further back you go, though, the more talking, or even sleeping, you encounter.

While it was painted nearly seven hundred years ago, apart from the very ornate lectern and lack of laptops, essentially the same scene is playing out in any university lecture theatre today. Students’ vastly varying responses to lectures might be written off as the vagaries of young people, but I suspect that the reason is more specific. Lectures simply suit some learning styles more than others.

Lectures simply suit some learning styles more than others.

A university education is based around the idea that if you teach people a subject’s underlying theory then they will be empowered to apply that theory in their practice. In other words, if you get the big stuff sorted, then the details will fall into place.

Now, if you have been following this series, you may have noticed that my essays often don’t function that way. Although I didn’t consciously set out to challenge essay structures or the theory-to-practice model, increasingly my pieces have tended to start with some sort of small incident or motif, which I can then use as a hook to take the reader outwards on a journey.

In other words, I like to start with the details and then gradually weave in and out until we arrive at the big stuff.

It was well over twenty years ago that I began to fully appreciate how differently people learn.

A group of communications students had started taking a photography class offered by our graphic design department. After a few weeks, I checked in with the photography lecturer teaching this new group. She said that she loved having the communications students, but she had to teach them quite differently to the graphic designers.

With the communication students, she only had to tell them once how to use a dark room (this all occurred before digital photography) and they would be able to score 100% on a test about it. Then they would go into the actual dark room and completely fall apart.

The graphic design students, on the other hand, had the greatest difficulty learning any of the theory, and loathed tests. You needed to explain everything three or four times in different ways and even then they still had a very sketchy idea what was going on. However, once they entered the dark room itself, they grasped the fundamentals almost immediately.

This served to highlight that people who learn through hearing (the predominant learning style among communications students) are going to do well in lectures and tests, but they are not necessarily going to be very practical. Good theory does not always translate into good practice.

Good theory does not always translate into good practice.

On the other hand, people with a strong visual/kinaesthetic learning style (like most graphic design students) struggle with pure theory but start thinking effectively once the sense of touch is engaged.

For them, starting with the theory is simply a waste of time because their preferred method of learning is the exact opposite of the university model – moving from practice to theory instead. The university’s theory-to-practice model is, in reality, an active barrier to their learning.

Over recent years, one of the big pushes by bureaucrats within universities of technology has been to try and rationalise teaching so that similar courses across different schools and departments can be merged. It is one of those proverbial (and possibly mythical) ‘economies of scale.’

For example, three small discipline-related courses on, say, philosophy, get combined so that they can be taught by just one specialist philosophy lecturer. Sounds fine in theory, but in practice it means that a lot of the students are taught in a way that fits neither their learning style nor their wider interests. The connection between their discipline and the philosophy inevitably gets erased.

By contrast, being introduced to philosophy by someone familiar with the students’ own disciplines and learning approaches allows for that disciplinary context to be woven back into the teaching. Students who work from practice to theory need those closer-to-home connections for the broader theory to seem relevant.

Students who work from practice to theory need those closer-to-home connections for the broader theory to seem relevant.

Laurentius de Voltolina painted that lecture theatre nearly seven hundred years ago. It would be nice to think that lecturing has improved a bit since then, and that students now get more out of their lectures. Sadly, I rather doubt this is the case, and nor will it be so while the supremacy of the theory-to-practice model remains unchallenged.

I discovered very early in my career that trying to use lectures to pass on knowledge simply didn’t work for my students – though I didn’t yet understand why. But lectures can still be very effective if one instead prioritises passing on one’s enthusiasm and telling good stories. These may not be retained in the memory but, done right, they stimulate students to go and learn for themselves.

Students all have different needs, and while universities can never meet every one of them, they could most certainly try harder to acknowledge differences in learning style. Making life better for practice-to-theory learners would be a good place to start.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion