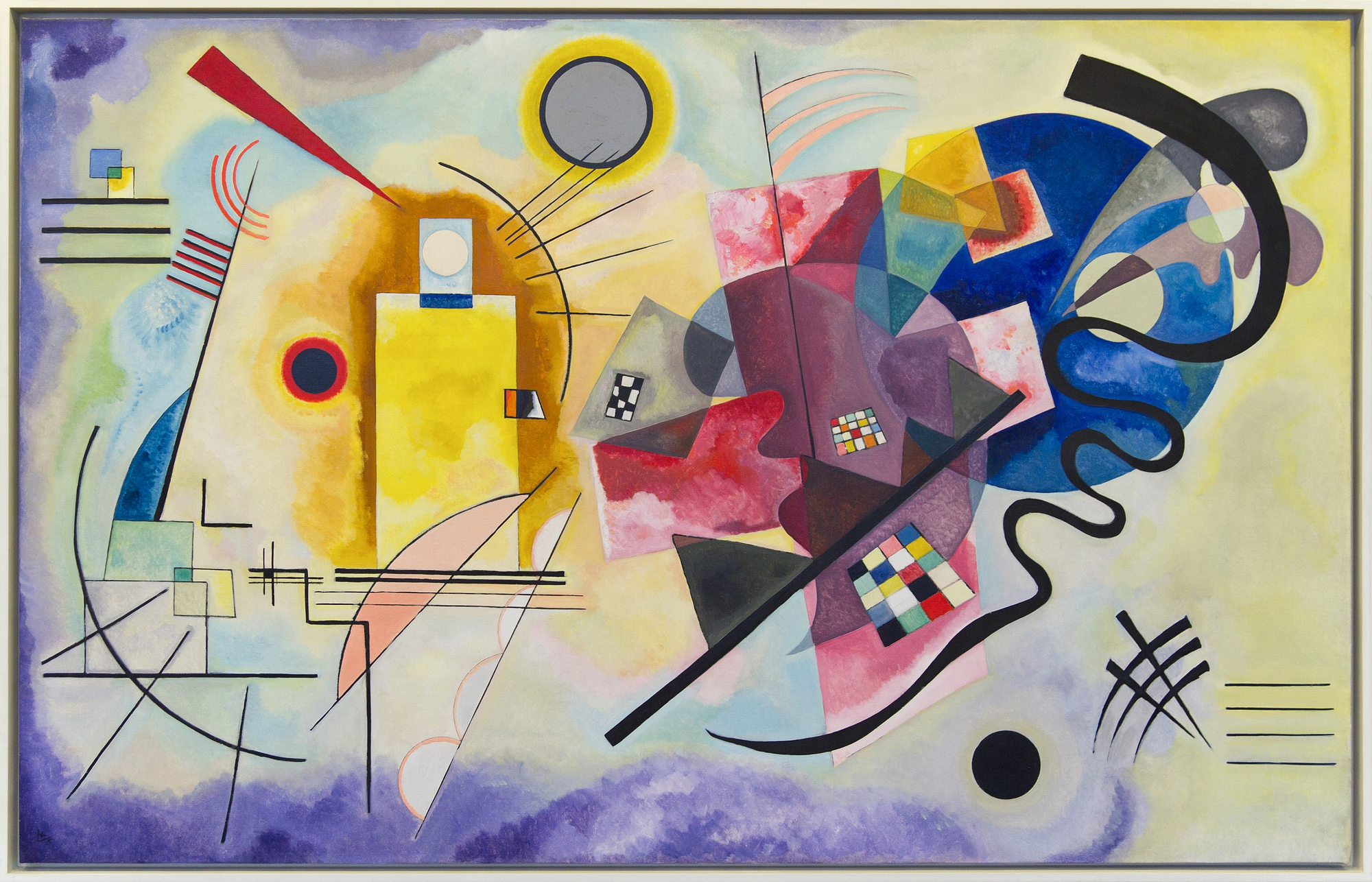

I first fell in love with Wassily Kandinsky’s paintings in 1975.

There was a large exhibition of his work at the National Gallery of Scotland and eighteen-year-old me was entranced. The liveliness of the shapes and the sophistication of his colour and design is nigh on impossible to put into words. I can’t, and he certainly couldn’t.

I would discover this the following year when I began studying art history. Kandinsky had written a whole book on his artistic theory called, promisingly, Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

Eager to understand his work from the inside, I bought a copy. It turned out to be detailed, dense and dry. The magic of the paintings entirely failed to leap off the page. Later, I would discover why.

Kandinsky is renowned as the inventor of abstract art. Although abstraction had been discovered by Beethoven (in music) decades earlier, and several other artists had done abstract painting earlier, Kandinsky was the person who turned an idea into a movement.

For Kandinsky music was the key. When he heard music, he literally saw colours, and it was these abstract dancing shapes that he tried to replicate in paint.

I knew about Kandinsky’s exotic music/colour overlap via his biography, but it was not until sometime around the early 2000s that I realised this was a broader phenomenon. It’s called synaesthesia – a syndrome where different sense receptors within the brain overlap, so that one sense triggers another.

After reading a fascinating article about it on the internet, I was moved to read some of it aloud to Helle, my wife. Her reaction was not what I expected. “What!” she said, “Doesn’t everyone do that?”

My wife assumed everyone saw colours when they heard music. ‘What!’ she said. ‘Doesn’t everyone do that?’

It turned out that she has two types of synaesthesia. For her, reading triggers sounds, colours and smells. It is a fully sensory experience. And when she tastes something, it conjures colours. She actually cooks by colour-matching the tastes. This experience seems so natural to her that she never questioned that it might not be shared universally.

When we asked our daughters, we found that one had Kandinsky’s music/colour synaesthesia. Others in the family had variations.

I discussed this with students and several had it too. One, I remember, was scathingly sceptical until I mentioned that numbers could trigger colours. “Doesn’t everyone see that?” he asked, with some chagrin.

This synaesthetic episode brought home to me just how much variation our brains have. Like most people, when I was younger, I had assumed that we experience the world in broadly similar ways. It was a revelation that I could have been married for nearly twenty years and not realised that there was this whole added dimension to my wife. It would be the first of several such discoveries.

For example, Helle could never use progressive lenses in her glasses. They make her dizzy. I, on the other hand, had no trouble adapting to them. And the discussion this engendered led to our finding an explanation for our different attitudes to mess.

Helle is all-seeing. She has a vast field of vision, whereas if I look at someone’s nose, I cannot see the rest of their face in focus. I have 20/20 vision, but only in a very small area. This means that while I don’t notice things right in front of me – let alone mess – clutter irritates Helle immensely.

At least understanding our different brain make-up has gone some way towards finding mutual understanding of something that had been a bone of contention in our marriage for many years.

In turn, appreciating my tunnel vision has helped me understand aspects of my own attitude to art and design.

Appreciating my tunnel vision has helped me understand aspects of my own attitude to art and design.

I love Renaissance paintings that are designed so that the composition draws your eye around the picture. It’s like visually caressing it over time. The Descent from the Cross by Rogier van der Weyden is the embodiment of such flow. Much of Kandinsky’s earlier work functions likewise.

On the other hand, modern design is often based on ‘gestalt’ principles and is intended to be grasped in a single moment of understanding and appreciation. It’s quicker, but I can’t do it. Unless the image is very small, I have to read it in sections and give it time.

This partially explains why, when possible, I like to improvise my calligraphy, and allow it to evolve as it goes, rather than making a ‘design’ first. I enjoy going with the flow, literally.

It would be wonderful if I could listen to music and make calligraphy out of it, but that’s not how I’m hard-wired. Nevertheless, when you look at Kandinsky’s work (and I recommend you do), maybe you, too, will see the music that is lurking behind the colours, and understand the picture that Kandinsky heard, painted, but couldn’t quite translate into words.

You could call it synaesthetics.

Each vignette invites readers to embrace the beauty of unfinished thinking and the art of holding life’s ongoing questions.

Member discussion