The Unseen Consequences of Critical Thinking

This article is born out of a sense of unease. Unease that something most of us regard as an indispensable intellectual tool may have a dark side. A side that is helping a divided world become gradually more divided, rather than less. A side that encourages incisiveness to grow teeth and snarl. I’m talking about that staple of Arts and Social Science education – critical thinking.

If you have been anywhere near a university’s arts or social science faculties over the last several decades, you will have encountered critical thinking in some form. I doubt there is a self-respecting academic who has not resorted to using the term in their learning outcomes. It is more or less a given, in academe, that a university education is intended to provide the world with better critical thinkers.

And yet, can you say that you were ever taught critical thinking systematically? I suspect that for many people the answer will be no. Sure, they know they are critical thinkers, but – like reason – it is something that everyone espouses, but virtually no one has ever been taught in a form that allows it to be held up to the light and examined. Or critiqued. So how has something that claims to be incisive become so fuzzy?

Now that question is a bit of sophistry. The situation is, of course, more complex than this simple dualism. To get a handle on what is going on, I want to initially do three things: establish how critical thinking developed and became ubiquitous; show how that development embedded some subtle problems; and highlight how aspects of critical thinking, and particularly its name, are becoming a liability.

I have long felt uncomfortable with what that word ‘critical’ implies, and the default attitude it engenders, yet without having a better alternative. Here I am going to propose one and suggest a way of dealing with these gnarly issues – one which amounts to giving critical thinking a rebrand.

Uncritical thinkers may, at this point, want to jump forward to the conclusion. It does, deliberately, sound cool. But that would be to make a leap with no evidence other than my ability to manipulate you. Hence, before getting to the need for a rebrand, I want to do what critical thinking is supposed to do – treat the available evidence in a fair-minded way before drawing conclusions. Hence, the initial need to sketch a history of the critical thinking movement and look at how it is defined.

Tracing the roots of critical thought

The capacity of humans to reflect on something, and formulate actions based on those reflections may well be a defining characteristic of our progress as a species. Certainly, for millennia, people have happily utilized sophisticated modes of thinking, and philosophers since Socrates have mapped out the key tenets of rational thought and enquiry. Socrates, particularly, is famed for his questioning technique that teased out the assumptions on which people’s thinking was based. Critical thinking can claim a long heritage.

Likewise, the terms ‘critique’ and ‘critic.’ With roots in two Greek words kritikos (meaning able to make judgements) and krinein (sifting or separating), and the later Latin term criticus (a judge), the terms have been used for many centuries, particularly in relation to literary criticism. Nevertheless, the attempt to fuse ‘critique’ with a particular approach to thinking in order to create something called ‘critical thinking’ has a more recent, and somewhat hazy history.

Most commonly, histories cite John Dewey as the originator of the term ‘critical thinking’. The early twentieth-century educational climate prioritised rote learning which, Dewey thought, produced conformist and shallow thinking. His aim was to improve students’ problem-solving abilities using scientific thought that was grounded in a mix of intellectual curiosity, speculative imagination and rational thought.

A good example of such thinking might be a recent article from Joe Y. F. Lau which takes issue with the lazy historical genealogies (like mine above) that simply credit Socrates and Dewey as critical thinking’s parents. He shows that pre-Socratic philosophers displayed critical thinking-like approaches, and that by 1903, when Dewey first used the term, it was already known in educational circles. In particular, he shows how, during the nineteenth century, interpretations of Kant’s ideas around critique and critical thought filtered through the University of Vermont and laid the groundwork for Dewey’s – and several other Vermont educators’ – uses of both the terms ‘reflective’ and ‘critical’ thinking.

Dewey, alongside this group, inspired an educational movement away from rote learning that initially saw a number of schools from the US Progressive Education Association change their curriculums to improve reflective thinking and problem solving abilities. After an eight-year study, their results were compared to those of students from traditional schools, and the progressive schools achieved markedly better outcomes.

Dewey himself had always prioritized the term ‘reflective thinking’ over ‘critical thinking’ and by the 1930’s had come to regard ‘critical’ as a subset of ‘reflective thinking’. However, the writers who reported on the Eight Year study used the terms interchangeably, and by the start of the 1940’s several studies had settled on ‘critical thinking’ as an umbrella term.

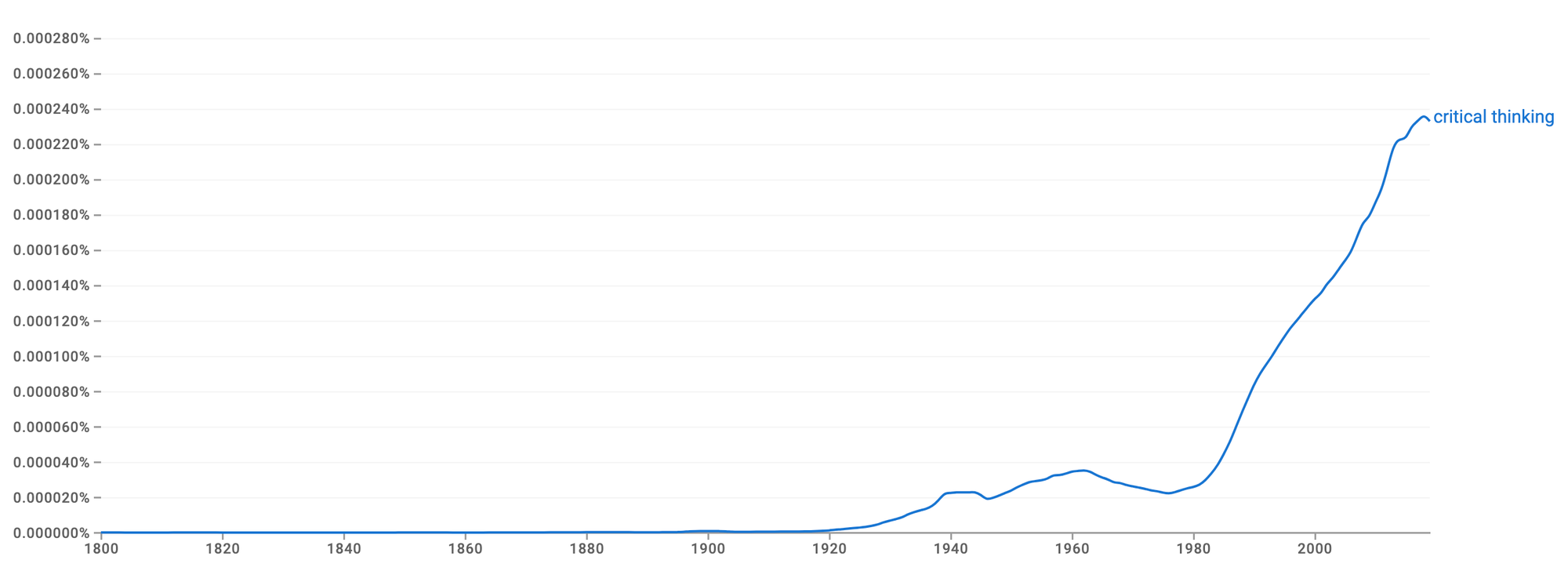

I have not been able to find a reliable historical account of how critical thinking became the default during this early period. It seems to have evolved more organically rather than through force of argument. Hence, I turned to Google Ngram Viewer (a tool that allows one to track the usage of words or phrases that are mentioned in digitised sources).

Although it needs to be used with care, the results from Ngram Viewer are, in this case, interesting. They show a surge of references to critical thinking between 1920-40 (in line with Dewey’s influence), a modest growth over the next twenty years (showing the effect of the 1940s study reporting), and then a decline between 1960-1980, at which point exponential growth began.

There is a good reason for the 1960s dip. From the late 1950’s, the dominant source in educational circles for the teaching of thinking was Benjamin Bloom’s “The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives,” commonly known as ‘Bloom’s taxonomy’. It created a progression of cognitive categories, which aimed to embed the reformist principles, putting rote learning of knowledge at the bottom of the heap and analysis, synthesis and evaluation at the top. Bloom, did not, however, emphasise the term critical thinking – though one can argue that the two approaches were strongly aligned.

Given its ubiquity today, it is hard to appreciate that, in 1985, Richard Paul was able to write that “until recently, the [critical thinking] movement was no more than a scattered group of educators calling for a shift from a didactic paradigm of knowledge and learning to a Socratic, critically-reflective one.”

From the start of the 1980s the movement consciously differentiated itself from Bloom and became more organised – with the 1981 First National Conference on Critical Thinking, Moral Education and Rationality quickly rebranding itself as the International Conference on Critical Thinking and Educational Reform.

This turned into a series of conferences that brought together critical thinking luminaries such as Richard Paul and Robert Ennis. Their goal was no less than creating a population “adept at gathering, analyzing, synthesizing, and assessing information, as well as identifying misinformation, disinformation, prejudice and one-sidedness.”

From these starting points, the critical thinking movement has become progressively more influential. The 80s and 90s were an era of academic turbulence, characterized by curriculum innovation and a plethora of newly minted Universities. I know. I spent decent chunks of that era writing new curriculum when the design diploma program I worked on became a degree. And the term critical thinking was incredibly useful in legitimising what we already did.

Nevertheless, becoming an academic industry that generates research and conference opportunities for academics – as critical thinking has done since the 80s – is not necessarily a recipe for simplicity. The goals of critical thinking may be straightforward, but tying down a definition is rather less so. Almost every writer, it seems, has a different approach, something that, in practice, has made it difficult for non-specialists to even get a straightforward definition, let alone a clear set of guidelines on how to teach it.

David Hitchcock, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, has done the hard work of summarizing the state of research on critical thinking definitions. His piece is worth reading in full if you want to get a handle on the varying views within the movement. Nevertheless, his conclusion, weaving together the various differing conceptions, is simple. Critical thinking, he believes, can be summed up as ‘careful, goal-directed thinking’.

A wonderful example of this, within a complex practice, can be seen in Linda Elder’s biographical sketch of Richard W. Paul. She shows how, throughout his work, Paul focused on fair-mindedness, empathy and accuracy. He sought standards of intellectual rigour that included “clarity, accuracy, relevance, precision, depth, significance and logicalness – to name a few.”

These standards then led to defining critical thinking abilities such as “gathering relevant information; making logical inferences; generating justifiable assumptions; following out implications logically; checking information for accuracy.” Paul defined 35 approaches (he called them ‘dimensions’) that all inform critical thinking – such as independence, fairmindedness, intellectual humility; avoiding oversimplification; questioning deeply and examining assumptions.

From Critique to Care: towards a new educational ethos

Writing an article like this, I have been constantly challenged by how to live up to such rigour when the format is necessarily compressed. Why choose Paul, not Ennis or other critical thinking theorists to exemplify the approach? In the end, all I can say is that I am not trying to give a complete or definitive account. I am responding to a journey of understanding that I have taken, and the examples given represent the flavour of my exploration.

That journey started because I wanted to unpick two things. The first was how I (and most others I knew) could get away with promoting ‘critical thinking’ whilst having only a fairly sketchy idea of what it actually was. The complexity and variety of what I discovered made me feel slightly better about that, as did the fact that it was apparently pretty normal for university staff to “lack a substantive concept of critical thinking.”

Secondly, I wanted to understand why, despite using the term, I never warmed to the idea of being a ‘critical’ thinker. The judgments formed seemed either too cold and clinical, or too weighted towards an automatically negative or skeptical disposition – one that very quickly turned into cynicism. And there seemed to be a particular emphasis on metaphors of depth and digging beneath the surface which had the effect of making it all too easy to unkindly dismiss everyday people’s ideas as ‘shallow’.

In other words, it felt as if critical thinking risked turning out graduates with negative, superior and dismissive ways of thinking. Then, more recently, I felt it had escalated into something more hard-edged and I suspected that this trend related to critical thinking increasingly being taught from within the ‘critical theory’ tradition.

Critical theory, for anyone not familiar with it, is a tradition founded by the Frankfurt school of social theorists in the shadow of national socialism, capitalism and authoritarianism. It aims, among other things, to uncover how dominant ideologies can be hidden within seemingly everyday thinking and it unpicks the assumptions that mask embedded discrimination and inequity. It thus has an important role to play.

Critical theorists like Stephen Brookfield have noted the overlap between critical thinking’s Socratic aim of uncovering assumptions on the one hand, and critical theory’s intent on the other. They have therefore unapologetically attempted to teach critical thinking within that disciplinary paradigm. In doing so, they are trying to get away from the analytical and pragmatic philosophical traditions out of which critical thinking arose, and which they see as tainted by dominant ideologies. Critical theory is unashamedly focused on changing minds – but with a clear political directionality.

Done well, Banfield’s project should be viable. But what happens when critical thinking is taught only through the lens of critical theory? Or when critical theory is substituted entirely? When students are not shown the two systems and allowed to form their own judgments? When they go away thinking they are critical thinkers, but are more properly critical theorists?

Socrates likened himself to an annoying gadfly. Critical theory frames itself in the same way. As black, Quaker, gay rights activist Bayard Rustin put it, it “speaks truth to power.” The gadfly is, though, almost by definition, operating in relation to a stronger oppressor. A single gadfly can annoy and prick conscience and pretention. But what happens when that single gadfly gains power, multiplies and becomes a judgmental, outrage-driven swarm? Cancel culture?

Just before I retired, we got a dog. We were living in a fairly conservative neighbourhood, and walking the dog allowed me to encounter people of a political persuasion very different to my own, and to what had surrounded me at work. Almost all of my new acquaintances turned out to be delightful humans – though admittedly they were dog people, which skews the sample. I found that we could discover agreement on a surprisingly large number of things. There were just a few collision points, which usually came down to their notion of fairness being less nuanced than one might encounter in a university context.

But my point is that without the dog, and the opportunity it afforded me, I might never have discovered all the points of commonality I had with people to whom I was politically opposed or realized the extent to which people on the right were serious thinkers, with points of view that needed serious thinking about on my part. People who, in Axel Honneth’s terms, deserved recognition. Whatever critical thinking I had been doing hitherto had not adequately taught me how to recognise and do justice to such views.

I write this in a political climate that feels fractured, fractious, and factional. One where the conservative and progressive traditions are getting further and further apart, and where ideological antipathies are growing. There are so many reasons for this, and Danu Poyner is looking at more of them in his series. But here I want to propose not only that we are not doing critical thinking well enough, but that the conflation of critical thinking and critical theory is a problem.

My concern hinges on the similarity between the two names. Both share the term ‘critical’, but that term increasingly seems to me to be more appropriate to critical theory. It is genuinely critical – in the sense of critiquing social structures and norms – and one could legitimately frame that activity as critical thinking. I see a place for both approaches, but I think that critical thinking in its original formulation has a different and distinct role to play.

When I started this piece, I was considering coming up with an alternative approach to critical thinking, based on more ethical and empathetic underpinnings. But during the process of engaging with it more fully, it has become clear that critical thinking can have an ethical base, and that leading critical thinkers are deeply aware of this. Richard Paul and Linda Elder, for example, have focused on this ethical aspect – the moral requirement to empathetically understand opposing opinions and to treat them with fairness and respect – and have worried about what critical thinking becomes when people use it in unethical or non-ethical ways.

This ethical facet of critical thinking seems to me to be desperately needed right now, but it is not conveyed in its name. And I think it needs to be. It is worth remembering here that Dewey specifically dropped the term ‘critical’ in favour of ‘reflective thinking’ and that the researchers who adopted it initially did not particularly justify its use – they seem to have simply inherited it from those early Vermont underpinnings.

The way out, as I see it, is less a case of radically altering critical thinking’s processes than one of rebranding it: giving it a name that distinguishes it from critical theory. One that better reflects what it does and embeds the ethical aspects of the activity more clearly.

One could return to Dewey’s ‘reflective thinking’ but I think that David Hitchcock has provided the basis for a better alternative. Hitchcock has similarly queried the term critical thinking, and suggested alternatives such as “reflective thinking” “rational thinking” and “constructive thinking.” Yet his definition of the critical thinking process was ‘careful, goal-oriented thinking’. So why not simply relabel the activity as ‘Careful Thinking’? That neatly balances the rigour of traditional critical thinking with the “ethics of care.”

Bruno Latour, in a 2004 critique of what he called “critical barbarity,” said, “can we devise another powerful descriptive tool [instead of critique] whose import … will no longer be to debunk but to protect and to care, as Donna Haraway would put it?” Harraway’s philosophical thinking on care, and its ethical implications, have been powerfully interpreted by Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, who has developed an approach to what she calls “thinking with care,” which she frames as ‘thinking with’, ‘dissenting within’ and ‘speaking for’.

Both Puig de la Bellacasa and Harraway’s ideas fit particularly well into the area of ecological care. Thom van Dooren gives a succinct overview of this, where he quotes Harraway as saying “caring means becoming subject to the unsettling obligation of curiosity, which requires knowing more at the end of the day than at the beginning.” It is hard to think of a better starting point for teaching ‘careful thinking’.

If ’careful thinking’ is implicit in such work, the term has been used explicitly elsewhere – albeit not often, or in ways that propose it as a substitute for critical thinking. It has occurred in medical writing since at least the 1980s. In general, however, such use has been focused on close attention rather than the full range of dimensions that critical thinking engages with.

More recently the term has appeared in both Christian and scientific contexts. A Christian program that aims to “set the stage for critical thinking” has been labeled ‘Careful Thinking’, while scientists Donald Stearns and Utteeyo Dasgupta have described careful thinking as “deliberately reconsidering our perceptions in an unbiased manner before drawing a conclusion [in order to] achieve a clearer understanding of a situation.”

It goes without saying that we can never be entirely unbiased, just as we can never totally think our way into someone else’s brain. Being unbiased and being empathetic are always goals rather than achievable outcomes. But they are nevertheless morally important goals. I suspect that postmodern relativism, having shown that goals like finding ‘truth’ are unachievable has had the effect of encouraging people to stop attempting to work towards them. Yet, like trying to be a ‘good’ person, surely it is still more worthwhile to make the attempt (in the face of impossibility than to simply shrug one’s shoulders and not bother?

That is why I think we should attempt to rescue critical thinking’s core from the fuzziness that surrounds it. It should be possible to both educate and encourage people to make the moral commitment to better understand both those that they disagree with, and their own unacknowledged biases and prejudices. And to do this both carefully and caringly.

The Careful Thinking I envision is thus grounded in the processes of the original critical thinking, but places particular emphasis on care, empathy and honest appraisal rather than ‘critique’. In adopting a spirit of curiosity, fairness, open-mindedness, reflectiveness and respect, I believe that the version of thinking that emerges has values that align with those of the Grokkist group.

All in all, I hope that this article has helped you think more about the issues involved and has encouraged you to reflect on and debate them for yourself. There is still so much good to be found within the critical thinking paradigm, when you dig into it. Nevertheless, I hope you can also see why I believe a rethink is necessary. Rebranding critical thinking as Careful Thinking could, in my opinion, make a substantial difference in moving education towards a practice that is no less intelligent, but rather more focused, caring and empathetic than much current critical thinking practice.

Member discussion