Making peace with pain

I was an accident. My mother’s first child died from meningitis. She quickly adopted three children to rescue her from heartache. It didn’t work. She became an alcoholic and abusive parent. Before my father left, when I was in elementary school, they had separate bedrooms and did not talk. I’m not sure how I was conceived. I was often awakened in the night by their yelling, throwing things, and physical altercations.

My mother suffered from untreated clinical depression and schizophrenia. My childhood and youth were spent trying to talk her out of taking her life. Arriving home from school each day, I had to determine whether my mother was sprawled out on the couch unresponsive because she had passed out from the bottle or was dead by overdose.

Our home was violent. My older adopted brother was a drug user and dealer, beat my mother and sisters, and routinely threatened to kill me with his Smith & Wesson pistol. I was estranged from both my parents when they died. Years later, I received word that my fugitive brother was no longer living. Neither is my best friend from high school, who took his life my junior year just hours after I left his home.

My childhood and youth were volatile, traumatic, and wounded me deeply. Despite the healing path I have walked over many years of my life, I will always have scars. You don’t “get over it”, but you learn how to carry it differently. Like tree rings or fault lines, these experiences marked me, but they don’t define me.

In my first published book, Divine Nobodies, I wrote:

“There are some memories you carry inside you like pieces of broken glass. If the walls of my childhood home could speak, they would tell the sad story of a woman ensnared in the depths of despair and a little boy who hated himself for failing to free her. Mom would tell me I was her only reason for living. Two hours later I would be pleading with her not to kill herself or run away from home. Before I knew multiplication tables, Mother relied on me as her counselor. Before my first date, she depended on me as she would a husband. Although a large crucifix of Jesus hung on the living room wall, she clung to me as her savior.”

Later in life, I came to understand the sorrows and heartaches of my mother’s life that I was born into. No little girl says: “When I grow up, I want to be a mother who hurts and wounds my children.” The truth is that damaged, wounded, and hurt people often damage, wound, and hurt others. That’s not an excuse, but it means any child could have been inserted into my place, and the result would have been the same. In other words, it wasn’t me. “Healing” has meant releasing the false messages I believed about myself as a result of the hurt experienced with my mom.

The healing process also involved stepping back and understanding my mother as one of eight billion people (including myself) who carries the same hurts, disappointments, fears, and heartaches common to all of humankind. This includes the same dysfunctional strategies we cling to for worth, love, and to escape our pain. We all reap the consequences of the hurt we cause others out of our unaddressed wounds and scars.

Frederick Buechner wrote:

“Even the saddest things can become, once we have made peace with them, a source of wisdom and strength for the journey that still lies ahead.”

In time, I chose to see my mother as an expression of the one and same, beautiful and transcendent ground of all being, regardless of how buried beneath her suffering it may have been to her.

The greatest gift my mother gave me was learning true compassion. As I learned that I could hold a space of compassion in my heart for my mother, I discovered that this space was big and deep enough to hold every person and all humankind.

The greatest gift my mother gave me was learning true compassion.

Because of my mother, I hold in my heart a genuine desire for the happiness and liberation of every person. I feel an unbreakable solidarity with the entire human family and carry a deep wish for the cessation of our suffering. I am committed to my own liberation, not only for myself, but for all human beings. By addressing the ignorance, delusions, and grasping at the root of my suffering, I can better aid others in their liberation. I am indebted to my mother for learning indiscriminate compassion.

In my adult life, there have been many traumatic life experiences that have shaped me. Here are ten moments that broke my heart but made me a person of greater humanity, compassion, courage, and a defender of the marginalized and oppressed:

- Locking eyes with a 12-year-old girl moments before she was dragged away to be victimized for the third time that day (as I posed as a sex tourist in a brothel as part of a forced child prostitution sting in SE Asia).

- Being called to a scene where a teenage boy was being cut down from a rope he used to hang himself in the garage, and informing his mother, who had just arrived.

- Riding in the back of an ambulance with EMTs and a young mother who had been beaten severely by her husband and told me she was bound to him by God.

- Seeing a line of little boys chained to poles, trying to roll their quota of cigarettes to avoid being beaten by electrical cords (as I posed as an investor at a child slave labor camp as part of a sting in SE Asia).

- Listening to the woman who couldn’t make eye contact with anyone else in the adult survivor support group meeting as she hung her head in shame and shared what it was like when her father molested her.

- Breaking the news to a fatherless 10-year-old boy that his heroin-addicted mother, who dropped him off at a babysitter that morning, was never coming back.

- Speaking with a closeted gay teen who told me he cut himself regularly, so God would know how repentant he was for his sin.

- Meeting a homeless person who insisted that they spend their last three dollars to buy my cup of coffee, because they wanted to feel the joy of doing something for someone else.

- Signing copies of my books for parents of terminally ill children at the Ronald McDonald’s House in Nashville, and the human bond I felt with them in their suffering.

- Visiting a man in prison on death row, who read Divine Nobodies and wanted to meet me to tell someone his story before he died.

Wounded and imperfect people save the world

Why did I share all those personal details about myself? As a reminder that all of us are the walking wounded. Some wounds are visible, some are buried deep. They mark where we’ve broken, where we’ve healed, and where we’ve vowed never to forget. They are not flaws. They are maps.

Wounds are initiations. They mark the moments we cross from innocence to awareness, from silence to voice. They invite transformation: when tended with care, wounds become portals, not prisons. They echo through others. Our wounds help us recognize the pain in others and offer presence without judgment.

Scars are healed wounds. They remind us of rupture and resilience. They can be honored as sacred sites, places where grief met grace.

We are the walking wounded, not because we are broken, but because we have lived. Because we’ve loved and lost, trusted and been betrayed, hoped and been disappointed. Our wounds are not signs of failure, they are the sacred inscriptions of our becoming.

Our wounds are not signs of failure, they are the sacred inscriptions of our becoming.

We are the walking wounded because we carry invisible stories. Grief, trauma, rupture, and longing are etched into our bodies, our breath, our silence. We move through the world tender and brave, still showing up, still reaching out, even when it hurts. To be human is to be wounded. To be awake is to walk with those wounds in the open air. We are not alone. When we name our wounds, we create space for collective healing.

You do not have to be completely healed to help others. In fact, healing is rarely a finished state. It’s a spiral, a rhythm, a vow. Helping others can be part of your own healing, as long as it’s grounded in awareness, boundaries, and humility.

Healing is not a prerequisite; it’s a path. Healing is nonlinear. We revisit old wounds in new ways. Helping others doesn’t require perfection. It requires presence. When integrated, our pain and scars become wisdom. You can say, “I’ve been there,” without pretending to have all the answers. When we help others, it helps us. Witnessing others’ journeys can deepen our own. It’s a reciprocal process if we’re open to it.

Imperfect people are often the most powerful helpers because they bring humility, empathy, and lived experience. Their imperfections don’t disqualify them; they deepen their capacity to connect. Imperfection is a bridge, not a barrier. People trust those who’ve struggled. Imperfection makes you human, not unreachable. If you’ve felt grief, shame, confusion, or failure, you’re better equipped to hold space for others in those places. Helping doesn’t require being “done.” It requires being present, curious, and willing to walk alongside.

A wounded healer is someone who transforms their own suffering into a source of healing for others. It’s an archetype rooted in mythology, psychology, and spiritual traditions—one that honors the paradox: the wound itself becomes the medicine.

Carl Jung coined the term “wounded healer”, observing that therapists are often drawn to healing because of their own wounds. Jung wrote:

“Only the wounded physician heals, and then only to the extent he has healed himself.”

and

“A good half of every treatment that probes at all deeply consists in the doctor’s examining himself… it is his own hurt that gives a measure of his power to heal.”

In Greek mythology, Chiron the centaur (half-man, half-animal) is the archetypal wounded healer: immortal, yet incurably wounded, he teaches medicine and healing to others. He carried a deep emotional wound that came from being a child of rape who was rejected by both his parents. He is quite literally a monster, and now, also an orphan and an outcast. But as the story goes, his primal wound became a source of healing for others and in turn brought healing to himself.

In Christian mysticism, Jesus is often framed as a wounded healer, his suffering becoming a site of collective redemption. In shamanic traditions, initiatory illness or trauma is often the gateway to becoming a healer. The wound is the rite of passage.

In Buddhism, the bodhisattva is a wounded healer. The Bodhisattva Vow is:

“Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to save them.”

This vow isn’t made from a place of perfection or transcendence; it’s made from compassion born of suffering. Bodhisattvas delay their own final liberation (nirvana) to remain in the world and alleviate the suffering of others. Their path is not escape, but radical presence.

Henri Nouwen published a book, The Wounded Healer, which I read many years ago. Some noteworthy quotes from the book include:

“When our wounds cease to be a source of shame, and become a source of healing, we have become wounded healers.”

“The great illusion of leadership is to think that man can be led out of the desert by someone who has never been there.”

“Nobody escapes being wounded. We are all wounded people. The main question is not, ‘How can we hide our wounds?’ but ‘How can we put our woundedness in the service of others?’”

The archetype of the wounded healer is one of the most potent motifs in trauma recovery, spiritual rewilding, and post-religious reconstruction. It honors those who transform their own suffering into pathways of healing for others, not by bypassing pain, but by metabolizing it into wisdom, empathy, and praxis. Many people who are deeply wounded by religion often become a source of help or healing for others who have suffered religious trauma.

Understanding the Wounded Healer

Carl Jung’s “wounded healer” archetype describes how a healer’s own wounds become the source of their healing power, especially in therapeutic relationships. Jung believed that the analyst’s personal suffering enables deeper empathy and insight.

The core pattern of the wounded healer looks like this:

Wounding: A rupture—trauma, illness, loss, exile—that destabilizes identity or meaning.

Descent: The wounded one enters the depths—grief, shadow, silence, or spiritual crisis.

Transformation: Through reflection, ritual, or relationship, the wound becomes a portal.

Return: The healer emerges not as a savior, but as a companion, one who walks with others through their own descent.

To become a wounded healer is not to chase suffering, but to metabolize your own into a source of wisdom, empathy, and creative service. What follows is a framework for better understanding the process. In this case, I’m going to use the example of a person who is deeply wounded by toxic religion.

Transmute the pain

The wound, loss, and trauma associated with leaving high-control or toxic religion can be metamorphized into a powerful source of help and healing for others.

Wounded healers often thrive in supporting others in their leaving-religion journey for many reasons, including:

- They’ve walked the terrain of rupture and reconstruction.

- They offer embodied empathy, not abstract theology.

- They honor pluralism and lived experience over dogma.

- They create rituals of belonging for those exiled from religious communities.

- They guide from within the wound, not above it.

One of the most important ways of supporting others in their healing journey is deep listening. It’s not a “fixing” mode, but relational presence and witnessing with care. In this context, deep listening occurs in several ways, including:

- Presence over prescription: The spiritual companion listens, not to fix or guide toward a doctrine, but to witness the unfolding of the other’s truth.

- Silence as sacred: Silence isn’t empty; it’s a space where insight, grief, and transformation can emerge. Deep listening honors pauses, breath, and the unsaid.

- Agency and autonomy: The listener trusts the speaker’s inner wisdom. There’s no agenda to convert, correct, or steer—only to accompany.

The wounded healer is especially able to offer this kind of deep listening and embodied witnessing. They don’t just offer advice; they embody the journey. They understand the complexity of deconstruction: fear, longing, nostalgia, and liberation. Their listening becomes ritual—a sacred act of repair for those silenced or shamed. Their presence says, “You’re not alone.” They validate grief, rage, confusion, and longing without rushing to fix or explain. Their story becomes a mirror, not a map, inviting others to find their own truth.

Their story becomes a mirror, not a map, inviting others to find their own truth.

The post-religion wounded leaver also has a language and framework that is useful to others. Shared language is the scaffolding of religious deconstruction. It is essential for healing, community-building, and meaning-making. It allows individuals to name harm, express grief, and co-create new spiritual frameworks beyond dogma.

Here are a few reasons why language is central to the healing process:

1. Naming the wound

- Epistemic liberation: Language allows us to name spiritual abuse, purity culture, gaslighting, and theological harm. This naming is not just descriptive—it’s liberative.

- Hermeneutical justice: Survivors of religious trauma often suffer from hermeneutical injustice—a lack of words to express their experience. Creating new language restores legitimacy and voice.

2. Dismantling dogma

- Deconstruction as linguistic critique: Rooted in Derrida’s philosophy, deconstruction challenges binary oppositions (e.g., saved/damned, sacred/profane) and exposes how religious language enforces power hierarchies.

- Unpacking inherited metaphors: Terms like “sin,” “salvation,” or “submission” carry layers of meaning. Deconstruction involves interrogating these metaphors and reimagining them.

3. Rewilding meaning

- Symbolic rewilding: Language becomes a ritual tool. New metaphors, like compost, spiral, mycelium, replace punitive or hierarchical ones. Nature becomes a symbolic reservoir.

- Archetypal remix: Figures like Jesus, Mary, or Buddha are reinterpreted through new language—wisdom teacher, grief bearer, mystic guide.

4. Building shared lexicons

- Community formation: People find each other through resonant words.

- Toolkits for healing: Visual frameworks, ritual guides, and symbolic maps become possible only when language is clarified and co-created.

- Continuity and vow: Language carries legacy. It seeds future healing.

It’s often the case that wounded healers have learned and acquired the language of healing and restoration, which they can share with others who do not have the words yet to name and process their experience.

Healing is not linear. The wounded healer revisits their wound. Each descent deepens their capacity to hold others.

The wounded healer archetype carries deep transformative potential—but also risks boundary collapse, projection, burnout, and unresolved trauma. Without self-awareness and support, the healer’s wound can unconsciously harm others.

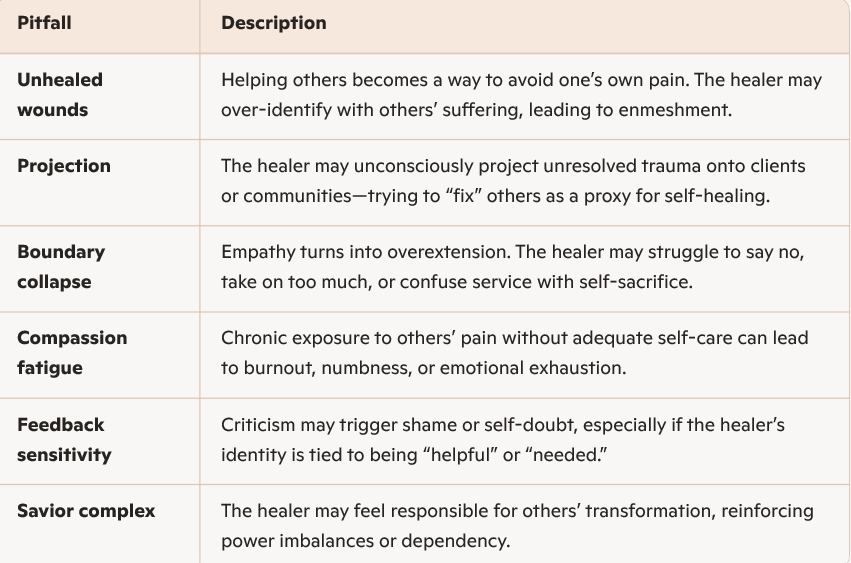

I created the below diagram to summarize some of the pitfalls of the wounded healer:

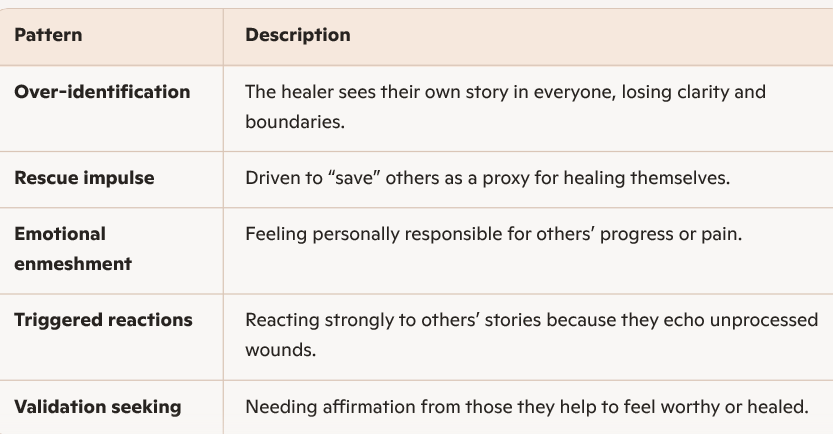

When working with others, wounded healers may experience “transference”, in which the healer may project their own pain, needs, or unresolved dynamics onto the person or people they are helping. I created another diagram to illustrate this:

Anyone who has been wounded and chooses to transmute that pain into healing for others can embody the wounded healer archetype. It’s not reserved for therapists, clergy, or mystics. It’s a posture, a vow, a praxis.

The core traits of a wounded healer include:

- Has experienced rupture: Whether through religious trauma, loss, illness, or existential crisis, the wounded healer has walked through fire.

- Chooses to metabolize pain: Instead of bypassing or suppressing the wound, they ritualize it, turning grief into guide, loss into legacy.

- Offers presence, not perfection: They don’t heal by being flawless. They heal by being real, attuned, and compassionate.

- Creates safe spaces: Their own journey equips them to hold others’ stories with empathy and non-judgment.

- Lives the vow: Their life becomes a ritual of continuity, honoring the wound as a portal, not a prison.

Jesus the Wounded Healer

Though I am not a Christian and dispute virtually all traditional Christian theology, I still find meaning in Jesus. One of those ways is seeing Jesus as the wounded healer.

Some years ago, I decided to take on a one-year experiment, testing the theory that anything Jesus ever did, I was also capable of doing. I published a book about the year, Being Jesus in Nashville: Finding the Courage to Live Your Life (Whoever and Wherever You Are). In that book I wrote:

“It is okay to feel what human beings feel. We laugh, cry, dance, feel ecstasy, even feel despair. It is how we know the world. It is how we live inside of our hearts and not dissociated from them.

Jesus didn’t theologize or spiritualize people’s suffering. Jesus faced suffering and tasted the depths of it. He leaned into it, endured it, and fully met others in their suffering. Jesus cared. Jesus wept. Jesus felt it all deeply. There’s something between living in denial and being swallowed whole by the pain and suffering of human existence, and Jesus lived there.

Being Jesus means that we go through life embracing it all fully and feeling it all deeply. That we don’t hide and try to protect ourselves. That we live. That we show up. That we laugh. That we cry. That we hurt. That we heal. That we care. That we love. And we wake up the next morning and sign up for it all over again.

Why did Jesus do this? Why do we? Because this is what it means to be human. You don’t get to pick and choose. It’s all of it.

There is a bliss that no amount of ache can steal away. And there’s an ache that no amount of bliss can rescue you from. Enlightenment doesn’t spare you from being human. You are supposed to be here. You are supposed to be human. You are supposed to feel both the bliss and the ache.”

Jesus can be understood as a radical companion, not a distant savior. His wounds symbolize solidarity, not supremacy. He walks with us through rupture, grief, and reconstruction. His crucifixion becomes a symbol of divine solidarity with suffering, not divine punishment. He is the one who bled with us, not the one who demands we bleed for him.

You don’t need to believe in literal resurrection to honor Jesus as wounded healer. You can walk with his archetype through grief, rupture, and rewilding. His story becomes a map for mutual liberation, not a mandate for conformity. His wounds become a vow to walk with the wounded—not to erase them. The cross can be seen as a fault line, the tomb as compost, the resurrection as vow.

Jesus can be seen as the archetypal wounded healer, not because his suffering is redemptive in doctrine, but because it’s relational, embodied, and symbolic. Jesus doesn’t bypass pain—he enters it fully: betrayal, abandonment, physical agony, existential despair. Jesus experienced a rupture in his own faith in “God” - “My God, why have you forsaken me?” His wounds are not hidden in resurrection. He shows them to Thomas. They become proof of presence, not power.

I walked away from Christianity many years ago, but there is a two-word sentence in the gospels that won’t let me give up Jesus entirely.

“Jesus wept.”

I finally learned why the statement, “Jesus wept” could only be a two-word sentence. There are no words preceding those two words, and there are no words following it. There are these moments in life where there is nothing more to say. Nothing that could be said. Nothing that should be said. It’s just a time to weep. Nothing fits before it or after it. Anything and everything that could be said rolls down you face in a tear and falls quietly to the ground.

I don’t know about a God in the sky who pulls strings, but I can relate to a Jesus who leaned fully into the lived human experience with vulnerability, courage, love and compassion.

For some years I have, from time to time, been working on the Religion-Free Bible (RFB). I rewrote that two-word sentence like this:

Jesus the Wounded Healer

“Anguish climbed from the bottom of his gut up through his chest and throat, and into his eyes with a power that even he could not contain. A lone tear quietly dropped from his eyelash. As it inched down his face, Jesus grieved the human condition, of which he was now inseparably a part. The heartache of humankind washed through him like cold rain. Jesus drank the cup of his true identity. He felt eternity in his soul, while human suffering coursed through his veins.

Life is beautiful. Life is agonizing. That was the deal, and there was nothing Jesus could ever do to change that. Gravity had it’s way with this solitary tear, and as it fell from his chin to the ground, Jesus was undone with sadness and compassion that stretched across every human wound and scar that had ever been felt. No divinity could save him now from his own human heart.

Jesus wept.”

– Jesus, John 11:35, Religion-Free Bible

In Summary

- We are the walking wounded, not because we are broken, but because we have lived.

- Healing is not a prerequisite—it’s a path.

- Carl Jung’s “wounded healer” archetype describes how a healer’s own wounds become the source of their healing power

- Anyone who has been wounded and chooses to transmute that pain into healing for others can embody the wounded healer archetype.

- Jesus wept.

“I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.”

- Carl Jung

Member discussion